By Thodoris Roussos

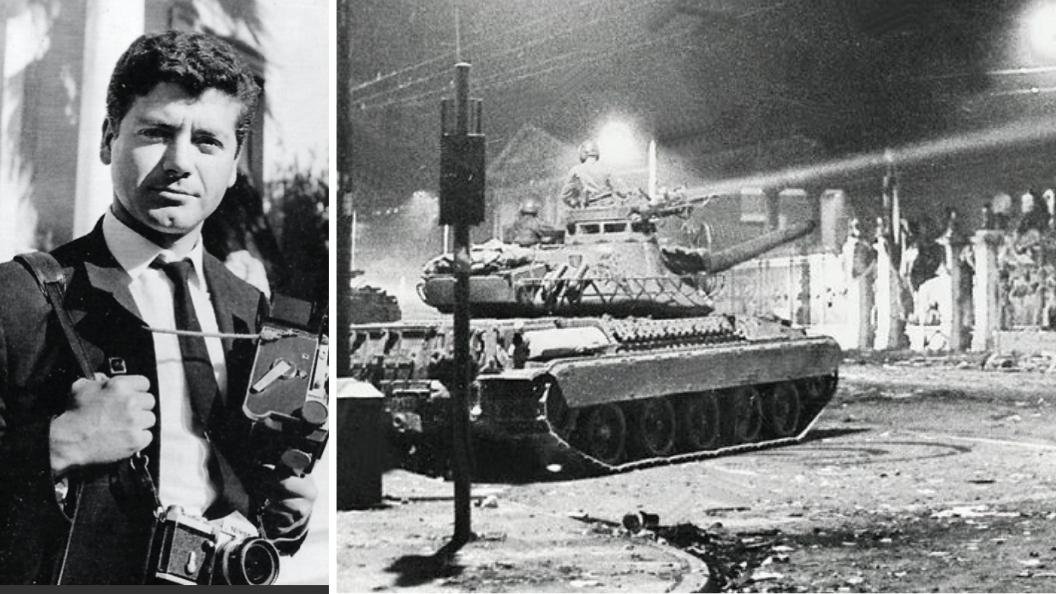

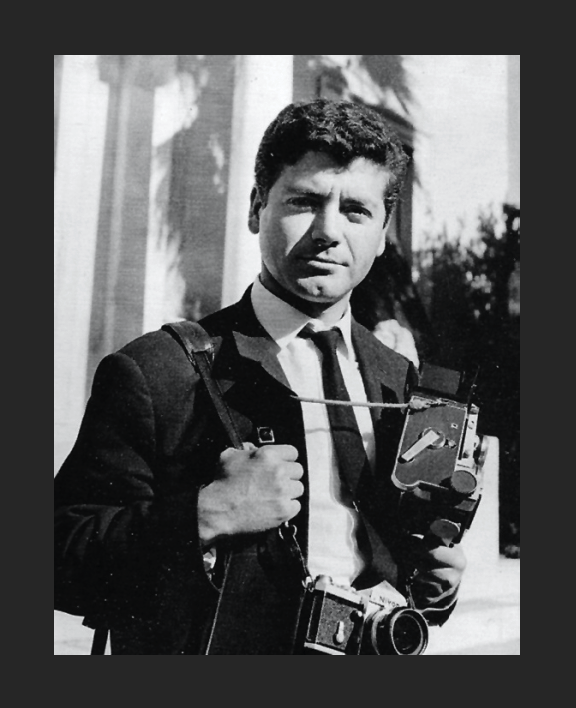

Some photographs taken by the then AP Greek photoreporter Aristotle Sarrikostas, together with the film of just 35 seconds of the Dutch cameraman Albert Courant, proved to be irrefutable documents and contradicted the original statement of the Colonel’s Junta that “nothing happened at the Polytechnic University”.

The only photoreporter who captured the moment of the invasion of the tank at the dawn of November 17, 1973, unfolds his memories and recounts in his own words the events of that evening.

“It was a suicide mission”

“It was five – six in the afternoon. It was dark. After I had taken several photos around the Polytechnic, I returned to the offices of The Associated Press, situated at the end of Academy Street-near the Parliament House, so that I could send the material to AP headquarters in New York. Back then, to send a black and white photo via transmitter and telephone line, it took 21 minutes! Today to send a photo it takes under 5 seconds.

Early on we photographed everything we could. And you know it wasn’t easy with the police, the army and the provocateurs to flash-photograph everything that was going on. It was like a suicide mission.

Take a picture of a police officer hitting students on the head with batons and sticks? That was impossible! They would of arrested me and send me to Bouboulinas (the security headquarters that was close to the Polytechnic).

Around 9pm, I heard a noise, a loud rumble.

They were the crawlers of the tanks, coming down Panepistimiou Street to go to the Polytechnic.

I immediately called my manager, Phil Dopoulos, who as soon as he heard the noise told me to leave immediately. I didn’t refuse, of course, but I needed someone with me. It was too dangerous to walk around in the dark. So I persuaded him to come with me.”

“We found ourselves in the middle of the phalanx”

“My manager had a Jaguar, with English plates. We got into his car and going down Americis Street we found ourselves facing the convoy of tanks.

As we were heading to the Polytechnic we were approached by a police patrol car. His driver – at the threat of a revolver – was cursing us and asking us to leave at once. The manager scared me. My reaction was instinctive.

I lowered the window of the car, looked at him, put my finger in front of my mouth, and with a long-drawn “Shhh,” I asked him to be silent! He was shocked.

He turned to his colleague and they drove off. Maybe when they saw the English Jaguar plates they thought we were the CIA or the Intelligence Service!

“I hid the films in my underwear”

“Moving between the tanks we reached Patision Street (the Road where the Polytechnic is located).

All tanks were set up in front of the Polytechnic with the searchlights on. We stood in a place about 40 meters from the main gate in Stournari Street. It was full of policemen, soldiers and provocateurs, whom I knew – they were wearing civilian clothes.

They were the ones who beat people with batons. As I was photographing, I was approached by a police officer.

“What are you doing here?” he asked, “You’re going to sit here and I will be watching you.” When he spoke to me he was heard by the rest of the police officers and soldiers close by. I was taking pictures without a flash.

“As many as I could and when a film finished, I would hide it in my socks, in my underwear. I gave some to my manager as well. I thought that was the only way to save the material.”

“The time of the invasion”

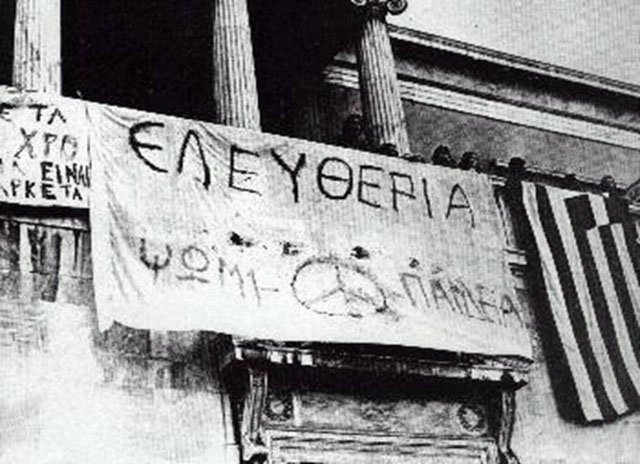

“I was nearby and I heard the students shouting at the police officers: “we are unarmed, we are brothers, come with us.” I could hear the sergeant in the main tank answering the radio. “Yes, sir. Yes, sir. At your command,” he was saying.

With the other hand he held a pistol. My manager walked out and I gave him all the film I had up to that time. It was midnight.

At 2:45am, on 17 November I saw the tank turning the turret in a contrasting direction from the main gate of the Polytechnic.

I thought it was going to turn and go away. This relief lasted for seconds because the tank suddenly accelerated releasing black smoke, and with tremendous force crashed on the main entrance, throwing the children who were upon the pillars of the gate on the ground, like oranges from the tree.

The tank broke through the iron door, crashed a Dean’s Mercedes that was just behind the door. The children who were on the sides of the door moved away. But you can imagine what happened to the ones that were up and behind the gate…”

“I was attacked”

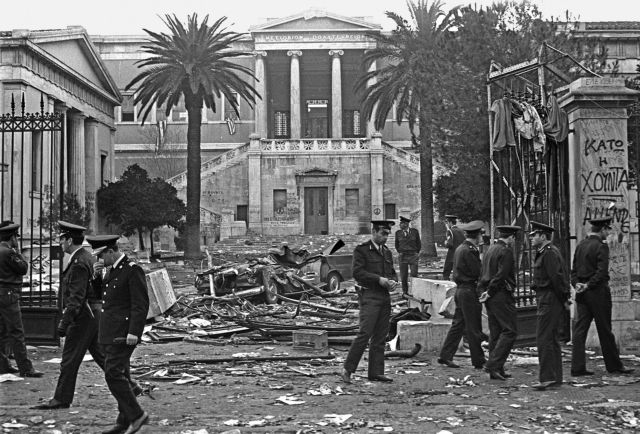

“As soon as the main gate fell and police and soldiers entered the Polytechnic University, I changed position to have a better point of view. At one point I perceived two policemen with sticks approaching me.

“They tried to hit me but I avoided the blows because I ducked in time. One of them pulled out a pistol and I started running zig zag because I thought he was going to shoot me. Luckily, he didn’t and today I’m here talking to you. I managed to get away.

I went back to the offices of The Associated Press to send the pictures of the tank’s invasion of the Polytechnic.”

“They cleaned the blood with hoses”

“Around 6am, I went out again. All Athens was covered by a heavy veil of smoke. The atmosphere was very heavy.

I went back to the Polytechnic University. It was messy. Discarded shoes, torn clothes, blood…

Police officers and firefighters were trying with hoses to wash the bloodstains that were on the streets and sidewalks”.

“My photos were irrefutable testimony”

“Around 11-12 in the morning the Deputy Prime Minister of the junta, Stylianos Pattakos, called journalists and photoreporters to tell us that absolutely nothing happened the previous night.

But a little later all the foreign newspapers were circulating with my pictures, which were irrefutable proof of the invasion of the Polytechnic.

Pattakos called us all back.

Greek and foreign correspondents and finally admitted it. “We had to step in to get rid of those brats,” he told us.

Fortunately there were these photographs, as was the film of the Dutch permanent correspondent in Athens, Albert Koeran, attesting to what had happened in Athens that night…”