By Anastasios M. Tamis*

In the last eight years I have turned my attention to contemporary Philhellenism (1945-2023) with particular emphasis on the Eastern Hemisphere, and this is due to the complete lack of relevant bibliography. On the contrary, regarding Classical Philhellenism, comprising Ancient, Hellenistic, Roman, Byzantine, as well as the form of the world movement that Philhellenism took in the mid-170th century, based in Germany, England and France, a rich bibliography had been developed in all the languages of the world.

With my book The Aegis of Hellas: The Continuing Vigour of Philhellenism, I aimed to highlight, analyse, and highlight the phenomenon of contemporary philhellenism, to:

(a) to refute the critics who claimed that Philhellenism is dead after 1945.

(b) to highlight the contribution of the Greek Diaspora as a permanent and consistent focus for the cultivation of global philhellenism in their host countries,

(c) to propose that the Diaspora and Philhellenism are the two main and fighting pillars for the revival of the humanities, which have been led since the mid-1960s to decline and eradication in the field of both teaching (the process of transferring and promoting knowledge) and learning (the acquisition of knowledge).

For the economy of this article, I identify two main manifestations, which for the sake of simplicity I will call “Classical Philhellenism” and “Contemporary Philhellenism”, noting that there is a strong interactive relationship between them.

By Classical Philhellenism I mean the study and appreciation of ancient Greek society, the ancient Greek world and with all that this implies, that is, its tradition, cultural heritage, history, literature, art, philosophy, natural sciences, mathematics, and other sciences. Obviously, such philhellenism is admiration for a lost society, and some idealisation can be traced from time to time. It is also a source of inspiration and lifestyle, it is an idealised model, of an ideology. We often omit the fact of androcracy and slavery, events that characterised the famous democracy of Athens, as well as most societies at that time, but these social weaknesses should not distract us from the enormous contribution of the Greek world, which taught over time the systems and mechanisms of governance of human societies. Any weaknesses of the ancient Greek world, which was and still is the idol of hundreds of thousands of philhellenes, should not alter, trivialise or destroy any surviving images of political men of the time.

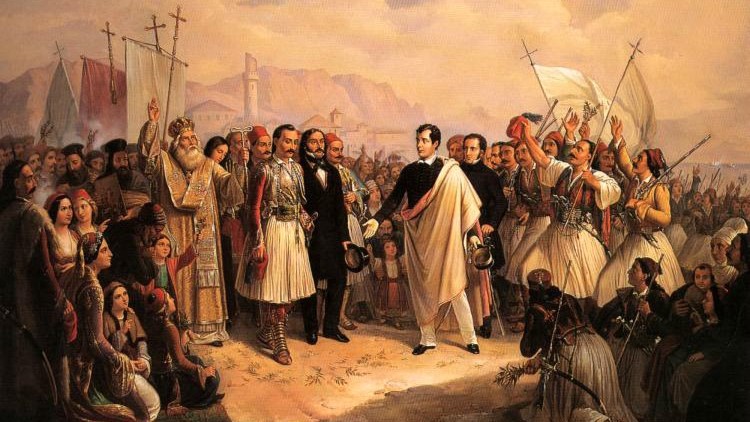

By Contemporary Philhellenism I mean the study of modern Greece, the teaching of Modern Greek language and literature, contemporary culture and the support of policies favorable to Greece. Such manifestations of Philhellenism developed strongly in and after the struggle for independence from Ottoman rule, although change did not come quickly in the university sector – for example, at the University of Oxford, where Classical Studies had long been available, Modern Greek was first introduced only in 1908 and endowed with a chair in language and literature in 1915. It remains the only Modern Greek programme in Britain to be a component of a BA degree.

Professor and Rector Michael John Osborne, when presenting my book at the Hellenic Museum in Melbourne, stressed that classical philhellenism prevailed in Europe early on and found visibility in the writings of famous writers and philosophers, and from the 17th century in the establishment of Departments of Classical Studies (i.e., Greek and Roman society) in most major universities. Indeed, classical studies became the dominant subject in universities, in Britain, France and Germany, and most political luminaries, writers and educated people were fully imbued with knowledge of Greek history, myth, literature and philosophy. At the University of Oxford, a leading exponent of classical education, there were in 1870 no fewer than 140 professors of classics (as opposed to a handful in the natural sciences).

Such dominance was strongly criticised by the great scientist, Thomas Huxley, at the end of the 19th century, but it is important to appreciate that, unlike modern critics of the Classical Sciences, he was in favor of continuing their presence and simply advocated greater diversity, so that the natural and social sciences would not be neglected. His hopes were fulfilled long ago, and only in the 1960s did a transformation begin, and, as I will note briefly, did not take the form that Huxley preferred, and the result was detrimental to the humanities.

There is, of course, a broader problem for the Humanities here. Because governments (and their institutions associated with them) are increasingly denigrating the Arts and Humanities, insisting that universities need to be much more attuned to the needs of the economy and workforce and devote much more time to teaching and training – and this has already brought about the elimination or marginalisation of many old fields of study that inform us about the foundations and history of Western civilisation. Let me add that LEARNING should be the primary characteristic of a university, and teaching should only be an element of this, not a replacement.

The Greek Diaspora, which lives in all neighbourhoods of the world, was the main cause of the formation of mechanisms for the promotion of Greek culture. The Greek Diaspora identified, cultivated and collaborated in identifying and promoting the philhellenic element in favor of Greece’s positions (political, social, cultural). The Greek Diaspora has nurtured tens of thousands of philhellenes to integrate and serve the modern Greek world, helped establish and operate Greek language chairs and departments around the world, contributed to the teaching and learning of diachronic Greek history and culture. Philhellenes have been the most effective functionaries of diffusion and promotion of Greek culture and modern Greece in the world.

*Professor Anastasios M. Tamis taught at Universities in Australia and abroad, was the creator and founding director of the Dardalis Archives of the Hellenic Diaspora and is currently the President of the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies (AIMS).