By George Vardas

In late 2014 the eminent international human rights lawyer, Geoffrey Robertson QC and his legal team, which included Amal Clooney, went to Athens to meet Greek Government officials to advise on the Parthenon Sculptures removed by Lord Elgin more than 200 years earlier and currently on display in the British Museum. Robertson and his team met Greek Government Ministers and it was agreed that they be commissioned to research and prepare a comprehensive legal advice.

Shortly afterwards, the legal team had a secret meeting with the then British Museum director, Neil MacGregor, in London to discuss a possible resolution but as Robertson writes “all paths were blocked by his passionate insistence that the Marbles should stay forever in the museum’s possession”.

Undeterred the legal team eventually put together a 600-page legal advice which was delivered in mid- 2015 to the new Tsipras Government in Athens, only to be rebuffed by successive culture ministers who insisted that the Greeks would rely instead on diplomacy.

In short, in less than a year Robertson and his team had been rebuffed by both the British Museum and the Greek State. Although there had been attempts to pull back from this negotiating precipice, the damage was done. The British sense that the Greeks lack confidence in their own legal and moral case for return and respond accordingly. Robertson himself was almost resigned to the fact that the “gumptionless” Greeks would never get back their ancient gods.

With his new book, “Who Owns History: Elgin’s Loot and the Case for Returning Plundered Treasure”. Robertson makes a compelling legal case for the return of the sculptures. Greece has not learned the lessons from the past and Robertson’s book should be mandatory reading for the Greek political and cultural establishment if they indeed want their marbles back.

Although Robertson surveys other examples of cultural treasures that have been taken – in many cases simply looted – during colonial times the main focus of his book is the case of the Parthenon Sculptures.

But what is so special about the Parthenon Marbles? As one commentator noted, the sculptured pediments, metopes and frieze removed by Lord Elgin symbolize the “entire body of unrepatriated cultural property in the world’s museums” and constitute an “essential part of our common past”. In the more than two hundred years since their removal, the sculptures that were ripped from the Parthenon have become a paradigm for forcibly-removed cultural treasures and invariably the debate about their return raises the question: who owns history and how is the past interpreted?

Since 1833 Greece has repeatedly and consistently sought the return of the marbles, through public and private written and oral requests and exhortations. Over that period Greece and Britain have also met on countless times under the aegis of the UNESCO Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin or its Restitution in case of Illicit Appropriation but have failed to make any progress as the British Ministry of Culture has continuously stonewalled efforts to hold any meaningful dialogue.

For over 30 years the committee has met and encouraged both parties to continue to negotiate, but to no avail. This came to a farcical head in early 2015 when the British Government formally declined a UNESCO offer of mediation, restating a by now familiar line that the Elgin collection was legally acquired and there is no point in having any discussions until the Greeks acknowledge the British Museum’s legal ownership of the sculptures.

The British Museum remains steadfastly defiant and has withstood the type of scrutiny that Robertson now urges. In large part this is due to the circular defence that the Museum and successive UK governments have employed for decades. Treasures within the British Museum are locked away by law (section 3 of the 1963 British Museum Act) which effectively prohibits their de-accession unless they are found not to be fit for display (due to physical deterioration).

As a result, in answer to requests for repatriation of items, the Trustees traditionally and predictably respond that they are prevented by the British Museum Act from deaccessioning even though , Robertson points out, the British Museum has never sought to have the legislation amended. And, of course, the British government of the day routinely replies that it is a matter for the Trustees and that the government has no present intention to amend the legislation. A cultural Catch-22.

At the same time, the British Museum describes itself as the museum of and for the world, embodying the collective memory of mankind and permitting the display of works of art across national boundaries. This crude appeal to universalism has been further refined by attempts to isolate the Parthenon Sculptures in London from their original Athenian origins and context – their so-called ‘Elginisation’ – by arguing that they are now more constitutive of a British identity because they have been in London for more than 200 years. Furthermore, the current division of the sculptures between Bloomsbury and Athens allows for “different and complimentary stories to be told”.

Robertson dismisses this claim by the British Museum as absurd because the Parthenon sculptures are part of the glory that was Greece and their inspiration certainly transcends cultural boundaries but for reasons which can only be fully understood and appreciated when they exhibited together, as Pericles and Phidias intended, and beneath the Parthenon. Robertson is particularly dismissive of the British Museum’s claim, noting that the so-called “different” story which the museum tells is actually a string of carefully constructed lies and half-truths about how the marbles were ‘saved’ or ‘salvaged’ or ‘rescued’ by Lord Elgin. And it is certainly not complimentary to the true narrative in the new Acropolis Museum.

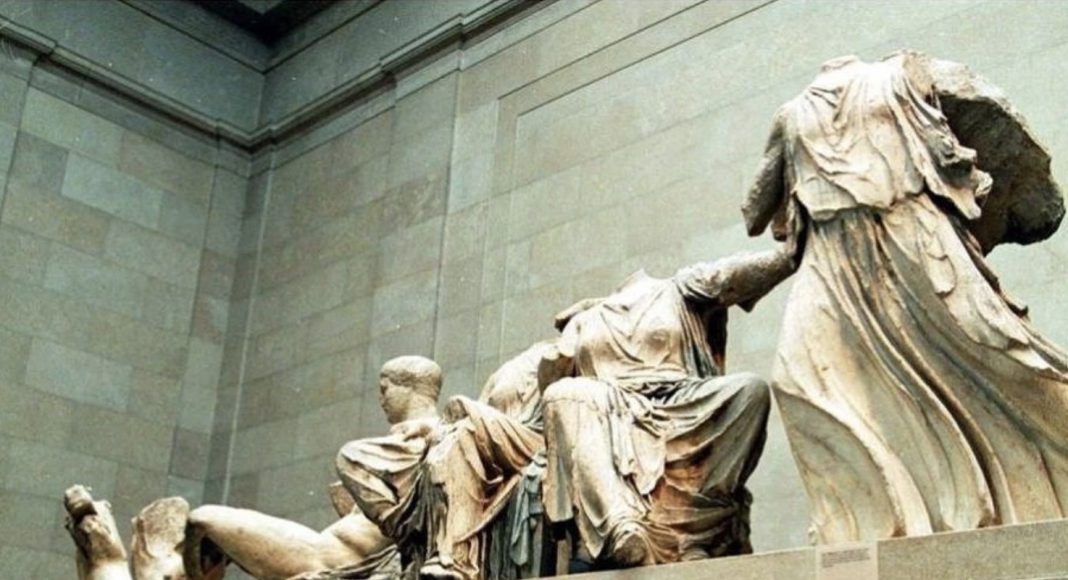

The full power and beauty and architectural context of the sculptures can only be appreciated if they are reunited with the surviving sculptures in Athens. In London, the sculptures are anachronistically displayed under artificial light in the Duveen Gallery. They give the impression of an old newsreel. The “unique wonder of the marbles” refutes the so-called slippery slide excuses by the museum. The Parthenon is unprecedented in human history. It is a “wonder of the world to be appreciated in the most natural way possible”.

As for the British Museum’s claims that it is a world museum, a ‘something for everyone’ pluralistic museum, Robertson points out that in the case of the sculptures the museum has jumbled artefacts from all over the world in a display that has no coherence. In the British Museum the marbles are simply “titbits in a cultural smorgasbord” whereas in the New Acropolis Museum they would literally come to light.

Some years ago Neil McGregor published “The History of the World in 100 Objects” which conveniently surveyed 100 artefacts in the possession of the British Museum. If you want to see the cultural world, just go to British Museum, was the mantra. According to Robertson this book could equally have been described as a “detective’s guide to stolen heritage in the British Museum”.

The highly contentious ‘loan’ of the pedimental sculpture of the River God Ilissos to the Hermitage Museum in late 2014 also attracts Robertson’s forensic investigation. This writer suspects that the British Museum did not obtain an acknowledgement from the Hermitage Museum or Russian authorities as to its ownership of the sculpture (in contrast to the demands it made of the Greeks when the issue of a temporary loan of some sculptures was raised earlier this year).

Robertson correctly points out that the delivery of the sculpture to Russia raised interesting legal issues because the loan required an export license and the granting or withholding of such licenses is clearly a matter of government concern and its capacity to intervene. This whole episode belies the UK government’s repeated claim that it has no power over the actions of the British Museum Trustees. It did have power to permit or refuse the export of the River God through its agent, the Arts Council England, but obviously chose not to. It could also influence the trustees to enter into non-binding mediation over the future of the marbles that UNESCO had sought., but meekly sided with the British Museum in rejecting mediation.

The colonial mindset and nostalgia for an imperial self-esteem persists. So how does Greece actually recover its sculptures apart from the usual talkfests?

At the outset, Robertson expertly demolishes the myth about Elgin’s supposed authorisation or firman to remove the sculptures or, as some scholars later attempted to argue, the retrospective approval by the Ottoman authorities in allowing the ships containing Elgin’s plundered booty to leave the port of Piraeus bound for London.

Robertson correctly points out that in in 1780 the French had sought to take moulds and the Ottoman authorities in Athens gave a limited permission but on strict terms not to remove any sculptures. How was it then that Elgin managed to desecrate the monument twenty years later? Elgin clearly abused his diplomatic office and through his agents in Athens he bribed local officials and persuaded the Ottoman Military Governor of Athens to allow Elgin’s workers to remove parts of the structure.

Robertson is also buoyed by the recent Sarr and Savoy report commissioned by the French president, Emanuel Macron, “The Restitution of African Cultural Heritage: Toward a New Relational Ethics” examining the fate of cultural property ‘acquired’ by France from Africa during its colonial wars on that continent and recommending that those cultural treasures should be returned from the “museums of blood”.

But he also recognises that the British will not be so forthcoming although an opportunity through Brexit presented itself in 2017. As Robertson explains, since the Parthenon had been declared by the European Union in 2007 as the most important cultural monument on the continent, it might have been thought that Article 3 of the European Union Treaty, which imposes a duty on European Union to enhance Europe’s cultural heritage, and Article 167, which requires that all EU negotiations must take into account the objective of conserving and safeguarding cultural heritage of European significance, would have made the surrender of Elgin’s ill-gotten gains a part of any deal with Britain. But as we know this came to nothing.

The way forward is through the customary international law if the Parthenon Sculptures are to be restored to their rightful place. There is an increasing jurisprudential recognition of the critical value of cultural treasures to national sovereignty, self-identity and dignity and consequently a developing recognition of the right of nations to possess and enjoy the keys to their ancient history by way of recovering from foreign museums and private collections their national cultural symbols. Such cultural treasures are deserving of protection under international law which is evolving and which recognises the sovereign right to claim unique cultural property of great historical significance taken in the past.

The British Museum Act has effectively locked up all legal remedies by the strict prohibition on deaccessioning and so Greece has to look to international legal remedies through either the European Court of Human Rights or the International Court of Justice. As Geoffrey Robertson once declared: “without litigation the Parthenon Marbles will remain in the Duveen Gallery forever”.

The least problematic way of doing this is for Greece to lobby UNESCO or the UN General Assembly to seek to have the International Court of Justice deliver an advisory opinion on the legal questions raised by the case of the Parthenon Sculptures and are cultural treasures that have been looted or plundered. Even an advisory opinion, whilst not strictly binding, can be very influential, particularly as other member States are invited to make submissions to the court in what would be an international cause célèbre.

Robertson’s own view in the end is uncompromising. The Parthenon was conceived as a unity and the sculptures were designed as an integral part of the temple. The Parthenon Sculptures are the expression of the local culture and evidence of the history of Greece, the country of origin and are essential to an understanding of the culture itself and its origins. They are an indissoluble part of Greece’s cultural patrimony and their restitution is fundamentally based on a respect for human rights and an appreciation for the culture that produced it.

Robertson’s book is a timely reminder that the reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures that once adorned Greece’s pre-eminent monument, as artefacts of unparalleled beauty, are part of a rich history that that does not deserve to be abused or re-written by the descendants of Lord Elgin.

Greece has the right to interpret its own glorious past.

George Vardas is the Fmr Secretary of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures and also Research Fellow of The Acropolis Research Group (www.targ.org.uk)