By Kathy Karageorgiou

Growing up in Australia as a 2nd generation Greek Australian in the 70s and 80s, I had a limited knowledge as to what Greek Independence Day, celebrated on March 25th, was really about. I knew it had to do with Greeks in the various dress forms of the day, rising up against their Ottoman oppressors, enacting a Greek Revolution.

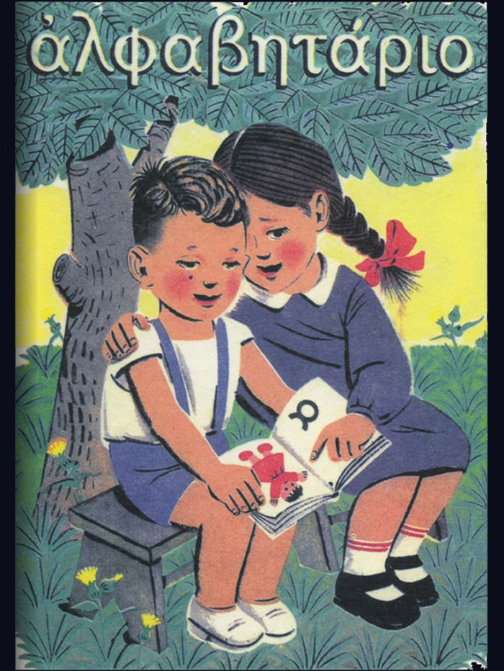

My weekly, four-hour Greek School lessons, did include history. We had textbooks straight from Greece’s Ministry of Education, and I was always fascinated by the Greek text with its intonation marks made up of various symbols, not to mention the grammar rules, and the great joy and pride I felt in my progress towards learning my mother (and father) tongue, Greek. Also imprinted in my mind from these Greek text books were their colourful and informative illustrations.

The inclusion of these pictures cannot be underestimated as complementary and entertaining, yet important learning tools. It was the pictures that enhanced the content of that first ever Greek school book ‘Alfavitario,’ that was for most of us our ‘official’ introduction in the 70s as Greek Australians to Greek culture through formal education.

Later on in higher classes of Greek school, came the history books whose pictures I still recall: The flags and dressed up men with large moustaches in fancy battle gear; Kolokotronis, Rigas Ferraios, Karaiskakis and others, whose names the teacher would painstakingly get us to repeat.

With the same verve, our Greek school teacher would try to explain these heroes’ roles in the Greek Revolution which resulted in Independence Day, and why it was celebrated annually on March 25th. We would recite poems on that day, in the hall of the Greek school and our parents could come and watch us.

I remember my eight-year-old brother hiding in a neighbour’s tree because he didn’t want to attend the celebration one year. We had looked everywhere. The only reason we found him in due time, was from the white foustanella costume he was required to wear for that day in honour of a revolutionary figure. The skirt part of the costume was sticking out amongst the heavy foliage of the tree!

Many decades later, as a mother having lived in Greece for over 25 years now, my sons have taught me more about the Greek Revolution than I recall (though this could be due to my lack of paying enough attention to Greek School teachers back in the day). Speaking to people of various ages in Greece, I realised that the Greek Revolution was taught in a basic, conservative manner which although conveying a sentiment of national pride, seemed somewhat rigid.

The 200-year anniversary of the Greek Revolution in 2021 changed this, thanks to creativity and technology. In my research to enhance my knowledge and appreciation of Greek Independence Day, I discovered an official site called: ‘1821 Observatory.’ This is a constantly updated site with information about the Greek Revolution from many perspectives – globally. Its plethora of interesting information ranges in scope from academic to arts and more.

Perusing this brilliant website, I discovered broader and more comprehensive views of what our ancestors and their friends – the Philhellenes – contributed to this fight for Greek emancipation from the Ottomans. I also began to see a new perspective; that of Greek Revolution’s significance on a global level.

The 1821 Observatory site directed me to the excellent Greek Community of Melbourne’s extensive online seminar /lectures, made during 2021, the Greek Revolution’s bicentennial.

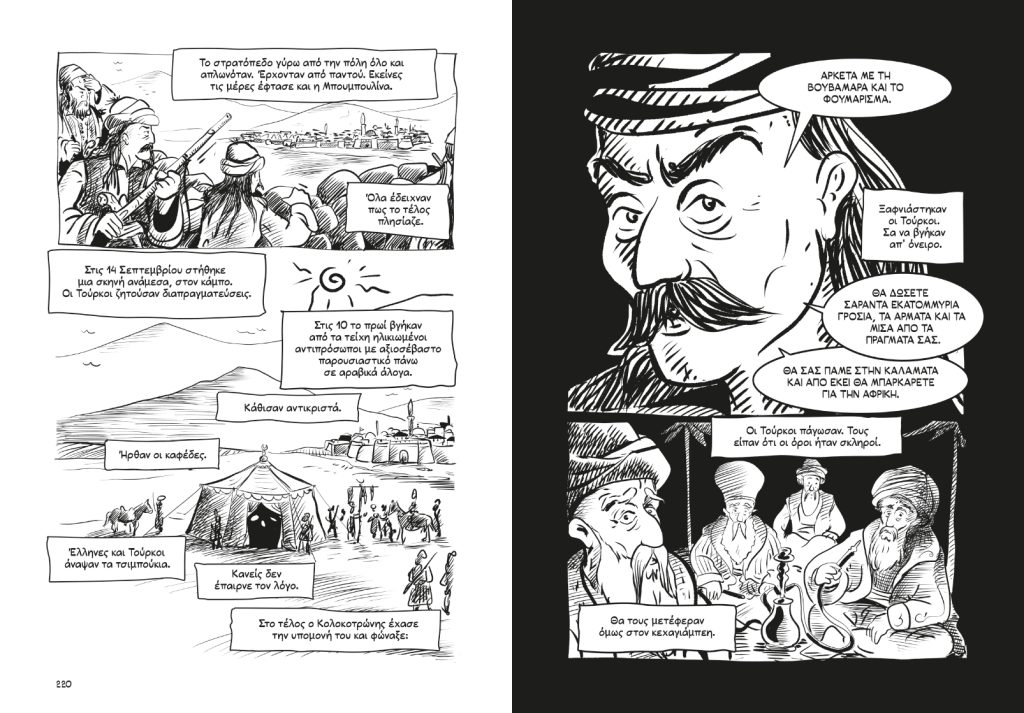

I also came across an over 700-page, graphic novel. It’s titled ’21: The Battle of the Square’ and portrays the Greek Revolution in an interesting, informative and unique way, reminding me of my previous reference to the power of illustrations combined with words.

To find out more, I spoke with the creator of this graphic novel,’ the popular Greek cartoonist Soloup (real name Antonis Nikolopoulos).

Apart from ’21: The Battle of the Square,’ Soloup has published many cartoons in local newspapers. He has also written and illustrated other graphic novels, for example ‘Aivali’ regarding the 1922 Asia Minor Disaster, while his latest – ‘Zorba’ is in keeping with the spirit of Kazantzakis’ original novel.

Soloup is also a doctor of the University of the Aegean and a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Communications and Technology there, while also teaching cartoon design and comics at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Smiling, he tells me about Greek Australians he’s met during summer holidays on the island of Kythera.

“They’re friendly, open hearted and always nostalgic for Greece. Having experience with other diaspora Greeks in Brussels, Monaco and recently in Canada, they’ve shown me another, more conscious-level Greece outside her actual physical borders,” Soloup says.

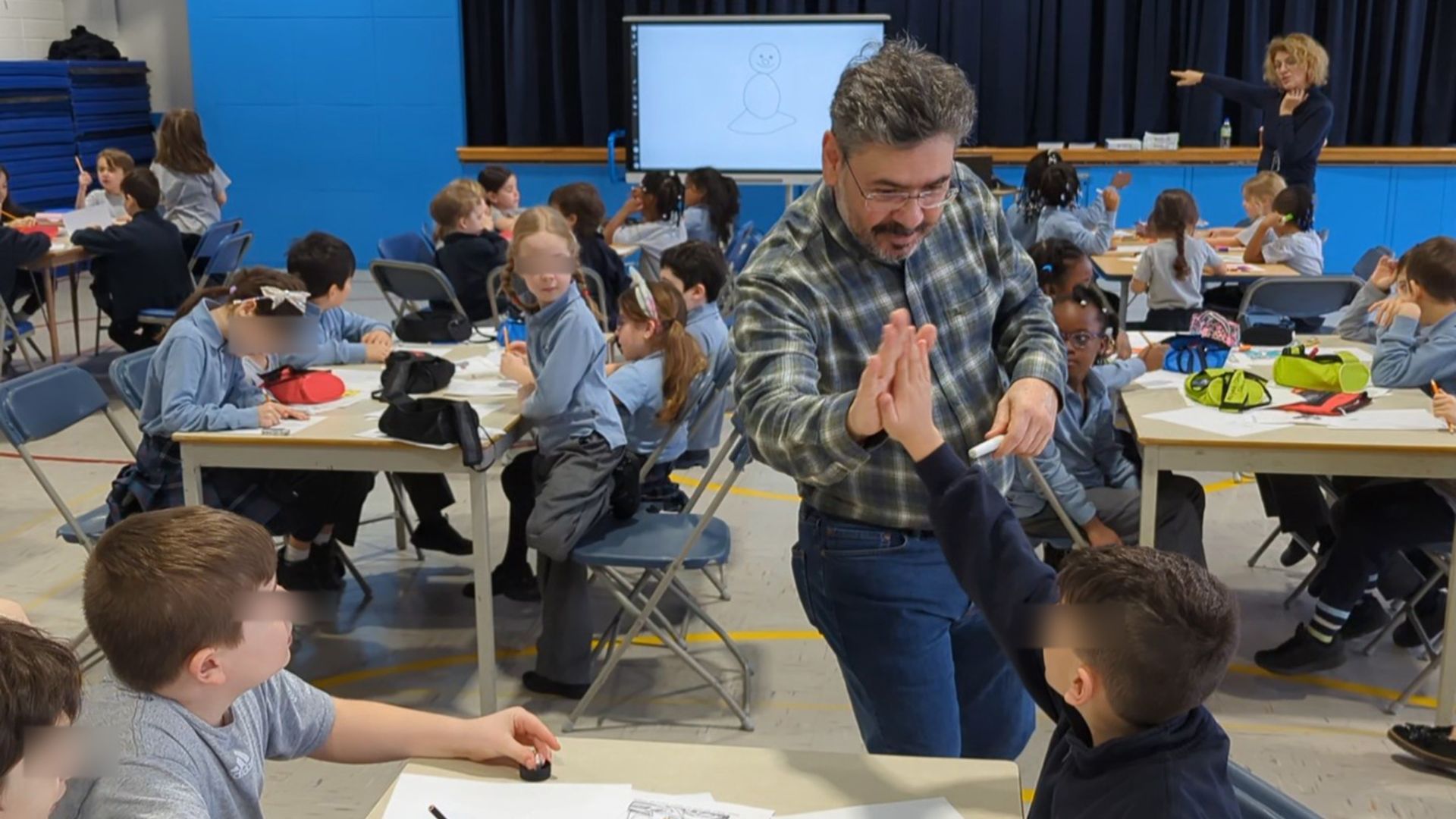

He goes on to describe his recent visit to Canada in February this year, on invitation by the Greek Embassy and Greek communities of Ottawa and Montreal.

“I did workshops with 1,200 young people there – 2nd and 3rd generation Greek Canadians. And like the Greek Australians I’ve met, I was really impressed at how alive Greece’s presence is for them, including the desire to be involved in all things Greek, even though most of them visit Greece in summer for holidays to see relatives,” he says.

According to Soloup, the many themes in ’21: The Battle of the Square’ did not only teach the young diapora Greeks in Canada about previously unknown aspects of the Greek revolution, he claims that it taught him many things too.

“As the book/graphic novel was supported by the Hellenic Research and Innovation Foundation and the University of the Aegean, under the auspices of the National Historical Museum, I too for example, discovered new facts: Details about the Exodus of Missolonghi, and about the destruction of Chios. The oppressive terms of Greece’s money lenders were revealed to me, as well as the events around the near execution of Kolokotronis during the first period of the Bavarian reign and council of King Otto,” he says.

“Modern Greeks today have the curiosity and insight to want to see their history without romanticising and glamourising it. This is what my graphic novel does by combining the joy of comprehension through my comic/cartoon illustrations with words – backed by academic researched documentation, in an entertaining and accessible manner for all people regardless of age.”

Wanting more information from the ‘1821 Observatory’ site regarding its constantly updated ideas on the Greek Revolution, I also spoke with academic Konstantina Tortomani; a team member of the Observatory.

Konstantina, in her 30’s, is also a University Lecturer at Greece’s Democritus University’s Department of History and Technology. Her expertise and interest in Philhellenism in the context of the Greek Revolution is what led her to join the 1821 Observatory team headed by Associate Professor Athena Syriatou.

Like Soloup, Konstantina is particularly interested in highlighting new perspectives of the Greek Revolution that may have been ignored in the past. This occurs through the 1821 Observatory’s site collating and disseminating local and international information on the Greek Revolution. The fact that this is an ever-evolving process, suggests both the pivotal role of the Observatory, but also of the Greek Revolution itself, an event prompting continuing thought and debate.

“Bringing up extra information as the 1821 Observatory does is very useful for the public because the Greek Revolution is not dead, not just something in the past, like a statue. Those involved in the Revolution were people, and so our thinking moves away from a black and white restricted interpretation,” Konstantina explains.

“For example, before joining the Observatory, I just considered the 1821 Greek Revolution as the birth of the Modern Greek state, nothing more, nothing less. But since joining the Observatory I realised it had global influence. The Greek Revolution was an idea that not only unified Greeks, but everyone – for equality.”

She stresses that modern historiography doesn’t see the Greek Revolution as an integrated continuation of the American or French Revolutions before it, but as an integral part of the global puzzle and as extremely important and unique in many aspects.

“The Greek Revolution was a sign-post of the modern world, in which newspapers, pamphlets and literary works played a huge part, as did Philhellenic societies around the world in where women, particularly in the USA, were involved for the first time. Their social and political involvement, such as charity work in collecting funds for the Greeks for example, lead to the beginning of women’s emancipation movements,” she says.

The wide global interest and influence of the Greek Revolution reached nations as far as Haiti, India, Japan and others, apart from the USA where the anti-slavery movement was ignited, Konstantina tells me, adding: “At the end of the day, people don’t always agree with their government’s stance… the international public’s interest in the Greek Revolution then, was like our current interest with Ukraine and Palestine is today. People care about what happens in the rest of the world.”

“Sometimes we think that the global is a threat to the local, but that’s not necessarily true, because in the Greek Revolution, locals fought alongside foreigners whether on the battlefield or on an ideological level for freedom.”

She clarifies that the Greek Revolution was not just nationalistic in scope, but influenced “the so-called Age of Revolution.”

Quoting the renowned British historian Eric Hobsbawn, “The struggle for social justice is a never ending battle, but one worth fighting for,” Konstantina adds: “There are still revolutions in the 21st century such as Black Lives Matter and Me Too.”

As for the Greek Revolution leading to Greek Independence, Konstantina proudly states: “We, the Greeks won, in terms of forming the first modern Greek Nation. Because of the Greek Revolution, Greece became the first nation that freed itself from the Ottoman Empire’s rule. It is unique because we had written Constitutions during the struggle, signifying the will of the people for equality; for a democratic state.”