By Georgios Psomiadis.

In the northern part of Greece’s Kythera Island, there is a small village named Karavas. It is so remote, that visitors end up there either to visit a relative or in most cases because they pick the wrong turn off the main road.

Tucked away somewhere in the village, there is a traditional bakery carrying 90 years of history and a unique family story within its walls that intertwines Greece and Australia.

It was 1932 when young Dimitris Koronaios moved to Australia with his family. The migration wave had already started at the beginning of the century and the Kytherians who were returning to their homeland had started spreading the word that Australia was “the promised land”.

“The conditions there were ideal for someone to build a career,” Pavlos Koronaios, Dimitris’ grandson, tells The Greek Herald.

“The rumour started spreading. People started their migration journey and said goodbye to friends and family knowing that probably they would never see each other again.”

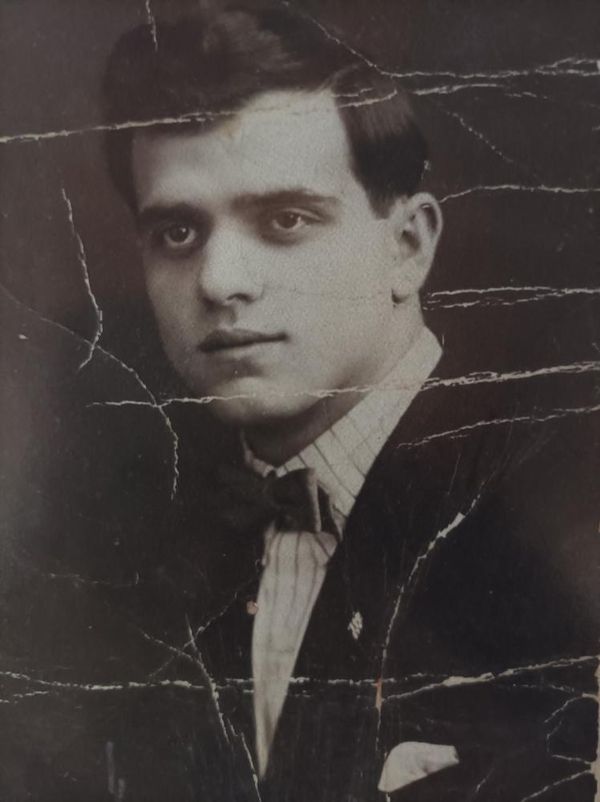

Dimitris, Pavlos’ grandfather, was a hard-working person and hungry for knowledge.

“Judging from what he would later create, he also had an amazing plan,” Pavlos adds.

The creation of the olive mill

In his 30s, having raised money and gained experience from doing odd jobs in Australia, Dimitris decided to come back to his birthplace. He left everything he had built Down Under and although at the time his decision would seem crazy to his friends, he never looked back.

“He did it because of the strong bond he had with his roots. He was missing Kythera and Greece,” Pavlos says.

“When my father, who later spent a part of his life in Australia too, talks about his time there, he says that there was not a day he would wake up in the morning without the desire to come back home.”

However, at the time, life in Kythera was hard. The island, a place of magnificent natural beauty, was isolated but this did not deter Dimitris from taking the risk to open the most modern olive mill of its time.

“What made it unique was neither its size nor the architecture, but rather the machines. It was the first mechanical-motion mill,” Pavlos explains.

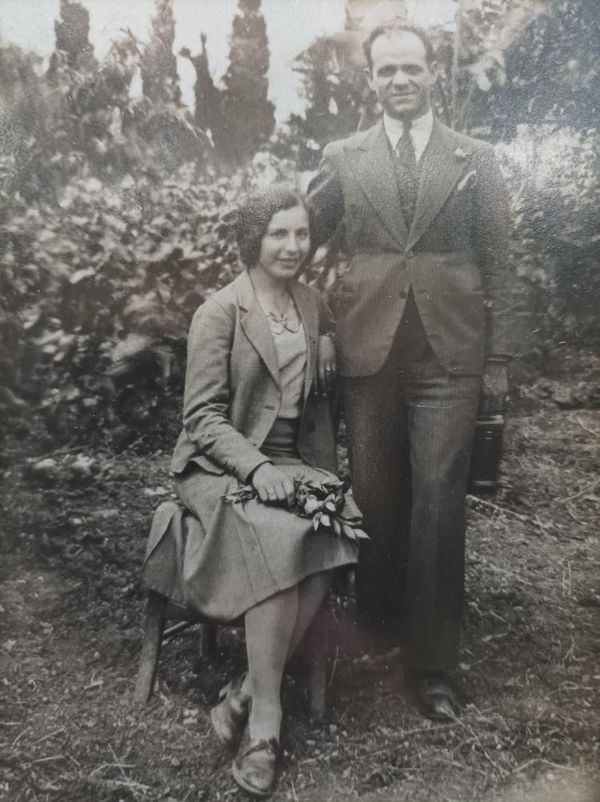

When Dimitris, who by then had become an influential figure on the island, passed away at the age of 57, his son, Giannis Koronaios, had already started his own journey to Australia.

At the time, another migration wave had begun and businesses on the island started closing. The olive mill, which had already changed hands, closed its doors in 1964.

For 40 years it was a building with old machines.

“A warehouse full of memories and garbage,” says Pavlos.

When he was born, the mill was next to his home and he has fond memories of growing up around the abandoned building.

“I would get inside and try to guess what was in there. It was like a treasure hunt for me,” he adds.

Back to the family

The abandoned mill would be Pavlos’ father’s painful desire for many years. The first time he went to Australia his sister was already there and he worked in restaurants.

“He taught us not to be afraid of trying to do something we loved even though we didn’t know how,” Pavlos says.

When he came back to Athens, his father became a fuel tanker driver. Later on, he moved to Kythera where he opened a souvlaki restaurant. Three years after Pavlos’ birth, in 1983, the family returned to the capital of Greece.

“My father was sad because his father’s heritage was deteriorating,” Pavlos reflects.

“I remember him making plans about how the building could be used. He was talking about the olive mill with love. There was something he had to fulfill first. Find his way back to the island”.

When Giannis heard about an opportunity to be a partner at one of the three bakeries of Kythera, he didn’t think twice. In 1992, he returned home. This was his first contact with oil rusks (paksimadia).

Pavlos grew up with his father’s dream. He visited Kythera every summer for three months. One night, in 1992, he helped him until he fell asleep exhausted on a bag of flour.

“One of the most magical characteristics of a bakery is its smell. It reminds you of home, and the figures of pappou and yiayia,” he recalls.

He was 23 when, fed-up of the fast-paced life in Athens and urged by the desire to give back to the community, he moved to Kythera shortly after.

Present and past united

When the first ‘European development’ funding programs started in Greece, Pavlos and his family had the idea to restore the old olive mill and turn it into a bakery.

“Until our opening in 2006 we were facing the same doubts that my grandfather faced. People said it would not succeed. Everyone was saying that it was an amazing idea, just in the wrong place,” Pavlos remembers.

But it was not. The Karavas bakery took off – proving that dreams can indeed come true.

When the collaborations with big supermarket companies began, oil rusk would become a symbol of change for the Kytherian village.

It was a local product, exported to many countries around the world. Karavas bakery would become a fundamental part of life on the island, giving jobs to 20 islanders, producing daily more than 1.5 tonnes of rusk and making the village known for its authentic products. People would come just to take a look at the olive mill, smell the pastries and taste a little part of history.

As for the Kytherians in Australia, the taste of home would get back to them in a package.

“Australia was a ‘must’ export destination. Around 60,000 Kytherians live there,” Pavlos explains.

At the beginning of the pandemic a collaboration started and now Greeks in Australia can find Karavas’ bakery oil rusks in fruit shops and restaurants around Sydney, Canberra and Melbourne.

“I know that we have created a very strong connection with Australia and even though it has faded a bit through the years, it is now strong again through the… path of the rusk. It is the perfect way to do it,” Pavlos concludes.

“People say ‘an image is worth 1000 words. But let me tell you, a bite is worth a million.”