By Dr. Themistocles Kritikakos (Historian)

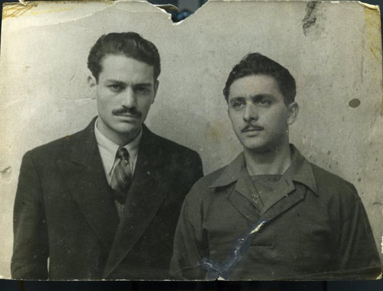

“Aera!” (Air!) roared Greek soldiers as they clawed over jagged rocks on the brutal Pindus Mountains of northern Greece during Italy’s 1940 invasion. My grandfather, Evangelos Kritikakos, fought alongside everyday men, farmers, and shopkeepers.

Torrential rain turned narrow mountain tracks into rivers of mud, where a single misstep could mean death. As October gave way to November, icy rain turned to heavy snow on the highest peaks. The cold cut through their threadbare clothing. With every charge toward Italian positions across this unforgiving terrain, they roared “Aera,” a war cry meaning to sweep the enemy away like the wind.

The cry of “Aera” rolled like thunder through mist-covered valleys as waves of Greeks surged over rocks and snowdrifts, pushing back invading troops stunned by their relentless force. Greek forces, familiar with the terrain, blocked and outflanked Italian troops advancing toward the strategic Metsovo Pass.

The Italians, mostly reluctant conscripts, poorly equipped and fighting for Mussolini’s imperial ambition, were increasingly demoralised. The elite Julia Alpine Division of the Italian army, trained for mountain warfare, was stunned by the Greek army’s refusal to fight against overwhelming odds.

October 1940 – March 1941: Defying Mussolini

At 3:00 a.m. on 28 October 1940, Italian ambassador Emanuele Grazzi delivered Mussolini’s ultimatum to Prime Minister Ioannis Metaxas demanding occupation rights across Greece. Mussolini reportedly boasted he would soon be drinking coffee at the Acropolis. Metaxas is said to have replied in French, “Alors, c’est la guerre” (“Then it is war”). Greeks in spontaneous unity embraced the symbolic “Oxi!” (No!).

By 13 November 1940, Greek forces had pushed Italian troops out of most frontier positions. Women and children from mountain villages transported supplies to the front along treacherous paths, often under fire. The Greek counteroffensive pushed deep into Italian-controlled Albania, capturing key cities such as Korçë (Korytsa), Pogradec, Sarandë (Agioi Saranta), and Gjirokastër (Argyrokastro).

Metaxas died on 29 January 1941 from terminal illness and was succeeded by Alexandros Koryzis, a former banker. When Mussolini personally supervised a final Italian offensive in March 1941, Greek defenders held firm across the Albanian front. Everyday Greeks had achieved one of the first Allied land victories in Europe during the war. Mussolini would never drink that coffee in Athens.

April–May 1941: German Invasion and Occupation

The Greek victory forced Hitler to intervene through Operation Marita to secure the Balkans and suppress British influence. Nazi Germany invaded from Bulgaria and Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941, and Greek troops in Albania were forced to evacuate.

On 18 April, as German forces closed in on Athens with overwhelming numerical and material advantage, Prime Minister Koryzis took his own life. King George II and his government fled to Crete on 23 April, and then to Egypt in late May, forming a government-in-exile.

Athens fell on 27 April 1941. As German troops entered the city, a story circulated: when soldiers ordered the Acropolis flag guard to surrender the Greek flag and raise the Nazi swastika, the young soldier Konstantinos Koukidis reportedly wrapped the flag around himself and leapt to his death, becoming a legendary symbol of defiance.

During the German advance, my grandfather fought against the Nazis. As gunfire erupted, a bullet meant for him ricocheted off his helmet just as he fell. His captain had pulled him down in time, saving his life. Around them lay the bodies of their fellow Greeks.

The Axis powers divided Greece into German, Italian, and Bulgarian zones of control. A collaborationist government was established in Athens. While parts of the Greek military in northern and central regions were forced to formally surrender to the overwhelming German advance by late April 1941, many soldiers evaded capture, went into hiding, or fled to join resistance groups. Greek resistance continued in numerous forms across the country, from guerrilla warfare to civilian-led sabotage.

On 20 May 1941, German paratroopers faced fierce resistance in Crete. Australian and New Zealand forces fought alongside Greek soldiers and civilians against the Nazis. Villages such as Kandanos and Kondomari were destroyed in reprisals, setting a pattern that would recur across Greece.

On the night of 30 May 1941, two students, Apostolos Santas and Manolis Glezos, climbed the Acropolis and tore down the Nazi flag. The act symbolised the resistance: spontaneous, civilian-led, and determined. Greeks fought in the mountains and countryside against the occupiers. Some historians argue that the resistance of Greece forced Hitler to divert forces to the Balkans, delaying Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union, by several weeks.

Winter 1941–1942: The Great Famine

The first winter of occupation (1941-1942) was catastrophic. Axis forces seized agricultural production and the Allied naval blockade prevented food imports. Distribution systems collapsed. Around 200,000–300,000 Greeks died from famine. People perished in the streets of Athens, families traded heirlooms for a piece of bread, and gaunt children scavenged for wild greens. Diseases, including tuberculosis and typhus, spread through malnourished populations. Nazi Germany forced Greece to fund its own occupation, draining the country’s resources, and triggering hyperinflation.

1942–1944: Resistance and Terror

Resistance emerged quickly. The National Liberation Front (EAM) and its armed wing, the Greek People’s Liberation Army (ELAS), expanded rapidly from 1942, while other groups such as the National Republican Greek League (EDES) also fought the occupiers. The most famous act of sabotage came on 25 November 1942, when resistance fighters and British agents blew up the Gorgopotamos Bridge, cutting the railway between Athens and Thessaloniki.

Greek women played a crucial role. They smuggled food, organised soup kitchens, maintained households, and served in resistance networks as couriers, nurses, and intelligence agents. Lela Karagianni, a mother of seven, founded the Bouboulina network, providing forged documents and safe passage for Allied soldiers and Jewish families until her execution in September 1944.

Iro Konstantopoulou joined the resistance at 14, sabotaged German ammunition trains, and was executed at 17 after weeks of torture, refusing to betray fellow fighters.

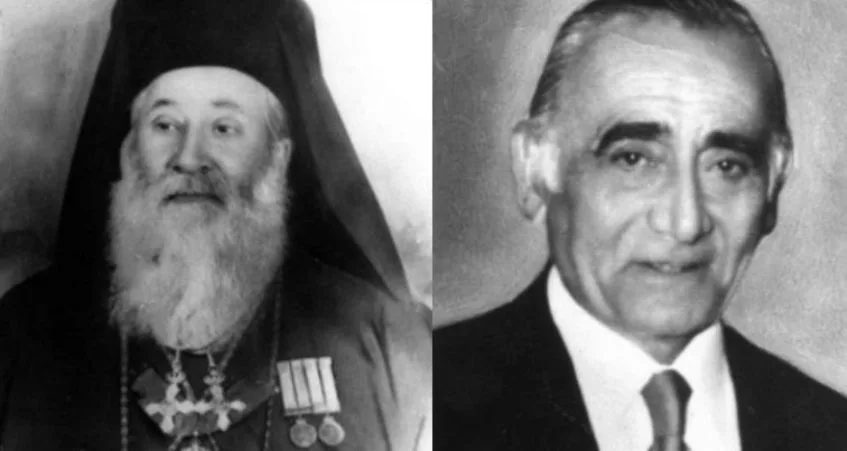

Before the war, approximately 75,000 Jews lived in Greece, including 50,000 in Thessaloniki. Between March and August 1943, Nazi authorities deported nearly all to Auschwitz-Birkenau. Fewer than 10,000 survived, among them about 1,800 from Thessaloniki. Across occupied Greece, clerics and civilians risked their lives to save their Jewish compatriots. Metropolitan Gennadios of Thessaloniki appealed in vain to halt the deportations, while Archbishop Damaskinos of Athens instructed priests to issue false baptismal certificates. Chief Rabbi Elias Barzilai of Athens destroyed community records to protect his congregation. On the island of Zakynthos, Metropolitan Chrysostomos and Mayor Loukas Karrer refused to surrender a list of the island’s Jewish population, instead submitting only their own names. With the quiet cooperation of civilians who hid and sheltered Jewish families, the Jewish community of Zakynthos survived the Holocaust.

Following Italy’s surrender to the Allies in September 1943, German forces occupied former Italian-controlled territories, including the Dodecanese. Italian troops were ordered to join Germany or face imprisonment or execution. On Cephalonia, over 5,000 Italian soldiers were massacred after resisting for over a week. Some survivors escaped to join Greek partisans.

By late 1943, much of rural Greece was under partisan control, with resistance networks numbering 1–1.5 million. The Nazis responded with brutal reprisals: around 1,600 villages in Greece were destroyed. In Kalavryta (December 1943), hundreds of men and boys were executed, and the town burned; nearly 700 civilians were killed overall. At Distomo (10 June 1944), over 200 civilians were killed. Similar atrocities occurred at Viannos, Kandanos, and Chortiatis. Greeks persisted in resistance until the German withdrawal.

Liberation and Aftermath

Athens was liberated on 12 October 1944, but for most Greeks, liberation brought exhaustion rather than celebration. In December 1944, violent clashes broke out in Athens between the forces of EAM–ELAS and British troops supporting the government of Georgios Papandreou, which had returned from exile. The Dekemvriana left thousands dead, exposing political divisions. Occupation and war had already claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in a nation of seven million. Civil war erupted between 1946 and 1949, claiming over 100,000 more lives and deepening political divisions for generations. Economic devastation forced mass emigration.

My father, like many Greeks of his generation, grew up amid the horror of occupation and war. My grandfather rarely spoke of those years. When he returned home, my grandmother barely recognised him: his hair and beard had grown wild, his frame hollowed by war. He had missed the early years of his children. The family understood he had witnessed horrors few could imagine, but no one pressed for details. My brother once asked him about the war when visiting him in our village of Elos in Laconia. His eyes fixed on something ever-present—the weight of memories he could not fully share. And yet, in the shadows of those memories, the cry of “Aera” endured, a symbol of the courage and resilience that carried him and many others through the war.

Surviving did not mean forgetting. The same men who had roared “Aera!” across the mountains of Pindus and resisted the Nazi occupation returned home in silence. This silence was shared with civilians, including women and children, who had endured the occupation, famine, and loss. Their traumatic experiences were passed on to the next generation, imprinted not in stories but in the silences between them.

Coming the week of November 3: The next article explores how the war reached Greece’s remotest islands, the Dodecanese, focusing on Kastellorizo.

* Dr. Themistocles Kritikakos is a Greek-Australian historian and writer. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Melbourne. His forthcoming book, Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Genocide Recognition in Twenty-First Century Australia, will be published by Palgrave Macmillan in December 2025.