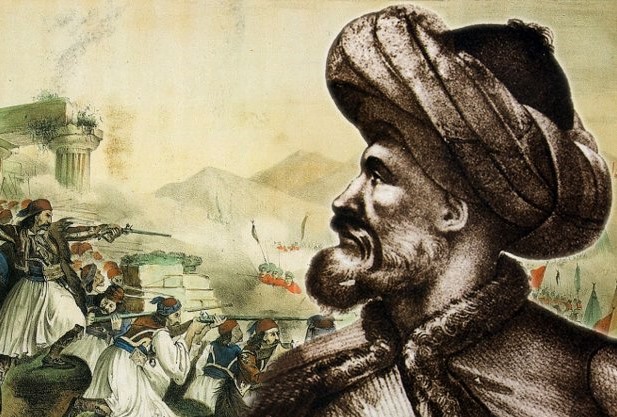

Mahmut Dramali Pasha was the leader of the Ottoman military campaign known as ‘The Expedition of Dramali,’ which took place during the Greek War of Independence in the summer of 1822. The campaign was a large scale effort by the Ottomans to quell the ongoing Greek rebellion.

But on this day in 1822, the campaign failed as Dramali’s army was defeated at the Battle of Dervenaki by a Greek army led by Theodoros Kolokotronis, Dimitrios Ypsilantis, Papaflessas and Nikitaras.

We take a look back at the history of this momentous event.

Background:

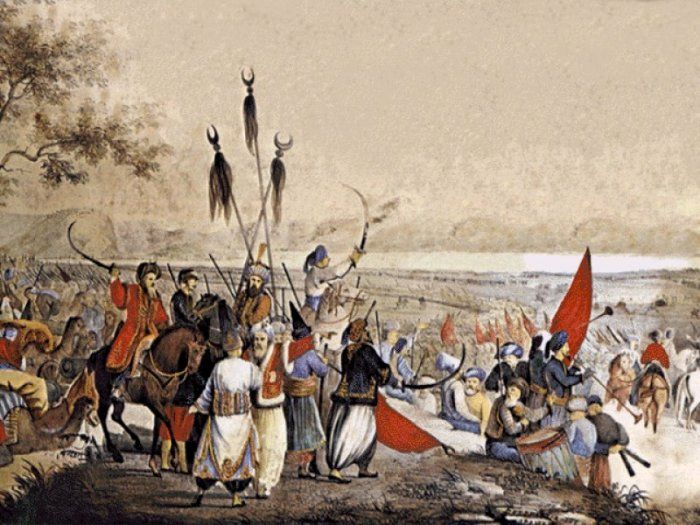

By the summer of 1822, the Ottomans were preparing to move southwards and crush the Greek uprising. They assembled an army of some 20,000 men and 8,000 cavalry with ample supplied and transportation at Larissa, which was entrusted to Dramalis.

Dramali was later appointed govenor of the Peloponnese with the rank of vizier, and undertook to form a military corps that would suppress the Greek Revolution.

Start of the campaign and retaking of Corinth:

In early July, Dramali set out from Zitouni (today Lamia) and found initial success. The Greeks, who were unprepared, left Dramali’s army largely unassailed and by July 17, Dramalis had retaken Corinth, which had been abandoned by its defenders.

At Corinth, Dramali held a military council to decide on future actions. Emboldened by the rapid progress and disintegration of the Greeks at the beginning of his campaign, Dramali decided to march his entire army towards Nafplio.

Trapped in the Argos:

Dramali and his army passed through the narrow gorge of Dervenaki and on 24 July reached Argos, where the Greek government had fled. Dramali left no guards behind him in the Dervenaki and he posted no forces where other gorges exposed his flanks.

On arriving in Argos, he found that its citadel, Larissa, was manned and that the Ottoman fleet, with which he had planned to rendezvous with at Nafplion, was actually at Patras. Instead, he launched an attack on the citadel.

The Greeks, under Demetrios Ypsilantis, held out for twelve days, waging a resolute defense before lack of water forced them to sneak out past the Ottoman lines in the middle of the night.

By this point, Dramali’s army had no more cattle, the burned grain fields supplied no subsistence, and the summer of 1822 was an especially hot summer, making water a scarce commodity. The plain south of Argos was a land of ditches, interconnected water lanes and vineyards, which hindered the Ottoman cavalry.

This gave the Greeks time to rally their forces.

Military leaders like Theodoros Kolokotronis and Petrobey Mavromichalis called for volunteers, who came flocking in, along with the kapetanei and the primates.

Kolokotronis pursued a scorched earth policy, aiming at starving the Ottomans out. The Greeks looted the villages, burned the grain and foodstuff they could not move, and damaged the wells and springs.

Dramali’s army was trapped in the sweltering Argolic plain at the same time as Greek troops surrounded them from all sides. On the hills extending from Lerna to the Dervenaki, Kolokotronis had 8,000 men. Around Agionori there were 2,000 troops under Ypsilantis, Nikitaras and Papaflessas.

Greek victory:

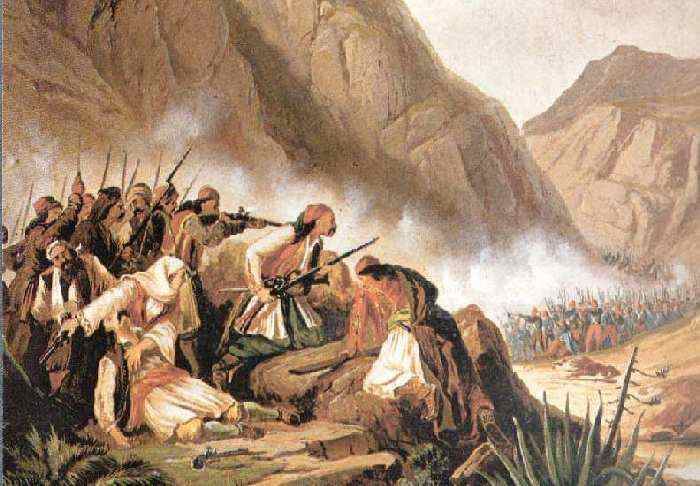

On July 26, Dramali dispatched an advance guard consisting of 1,000 Muslim Albanians to occupy the passes. The Greeks brought down devastating fire and then charged, slaying the Ottomans in vicious hand-to-hand fighting. Very few of the Ottoman light cavalry managed to escape.

On July 28, Dramali attempted to evacuate his main forces by way of the route through Agionori. Here he came up against the Greeks under Papaflessas who was holding the main defile (Klisoura).

Unable to proceed, he soon found himself assailed by Nikitaras and Ypsilantis who made a forced march from their positions at the village of Agios Vasilis and at Agios Sostis, where the Greeks again annihilated the Ottomans by ambushing them in a narrow defile.

Although Dramali himself with the main troop of delhis managed to force his way through and finally reach Korinthos, the Greeks captured all the baggage and the military chest, and they annihilated almost completely the unmounted personnel of Dramali’s army.

Dramali’s campaign resulted in a disaster of great magnitude: Out of the army of more than 23,000 with which he entered the Morea, barely 6,000 had survived.

The extent of the Ottoman defeat became proverbial in Greece, where a great defeat is still referred to as a “καταστροφή του Δράμαλη”, i.e. “Dramali’s disaster.”