By Ilias Karagiannis

My first night in Yerevan ended intoxicatingly. The wine, the conversation with Maria and Aram, all pieces in the puzzle of my stay in Armenia’s capital had been carefully placed.

A city that hesitates between Western and traditional character. A collective struggle for dominance, which certainly won’t heal the wounds. Memories that even today “bleed.”

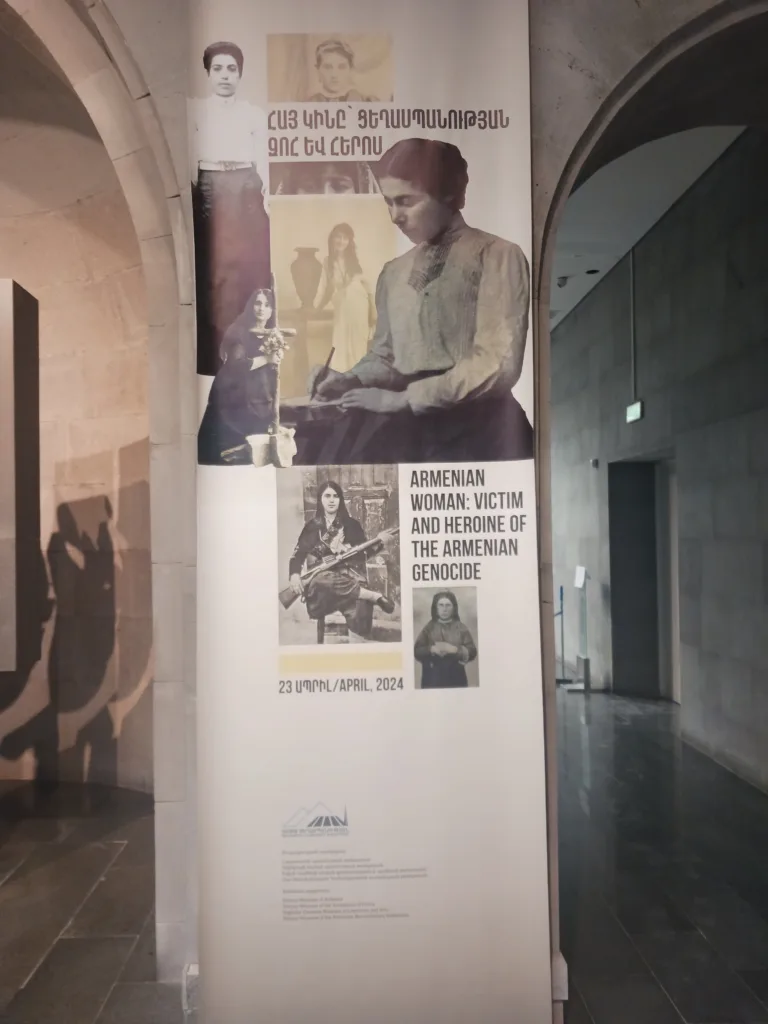

It was the 23rd of April 2024, and Aram, in our discussion, tried to convince me to visit Tsitsernakaberd the next day. The 24th of April was dawning, the day of remembrance for the Armenian Genocide by the Turks in 1915, and a strange, electrified atmosphere had spread like a shroud over Yerevan. It cocooned the Armenians.

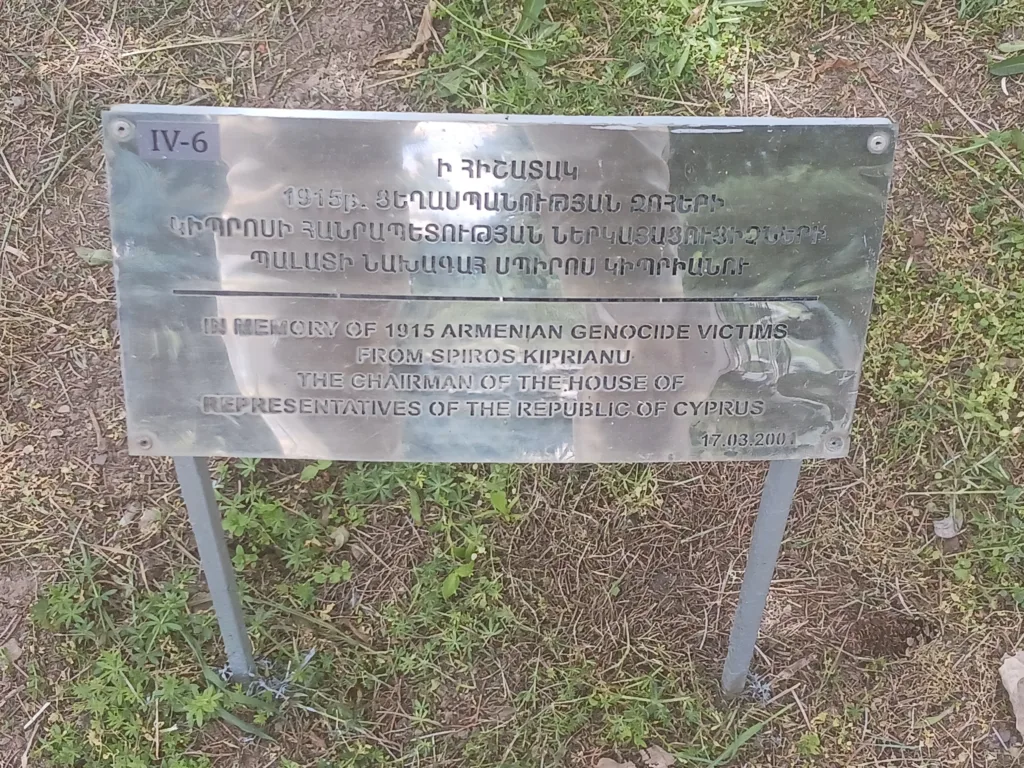

After an hour’s walk the next morning, I reached the hill of Tsitsernakaberd, where you can see a panoramic view of the entire city, and there stands the Genocide Museum and Memorial.

The stone mass of the Memorial looked heavy as it stood proudly on the hillside. A monument of pain and memory for the genocide.

Children laid flowers before the Eternal Flame, as they do every year on this day.

This year marked 109 years since the days when Armenians began commemorating “Red Sunday,” the day when the Turks launched a pogrom of persecutions and murders against Armenian intellectuals, essentially marking the beginning of the Armenian Genocide, which would result in approximately 1.5 million dead.

On the 24th of April, 1915, the Ottoman Empire’s Minister of Interior, Talat Pasha, ordered the arrest of all Armenian intellectuals in Constantinople, as well as members of the upper Armenian classes. About 2,000 people would be taken to Ankara and executed. The aim was to deprive the Armenian population of the Empire of its natural leadership. Few would escape.

Silence and mourning in the Museum

Passing the entrance of the Museum, located in an underground space, I irrevocably left behind the noise of the city. I entered a world of silence and mourning, where every object, every photograph, every testimony “screamed” the atrocity.

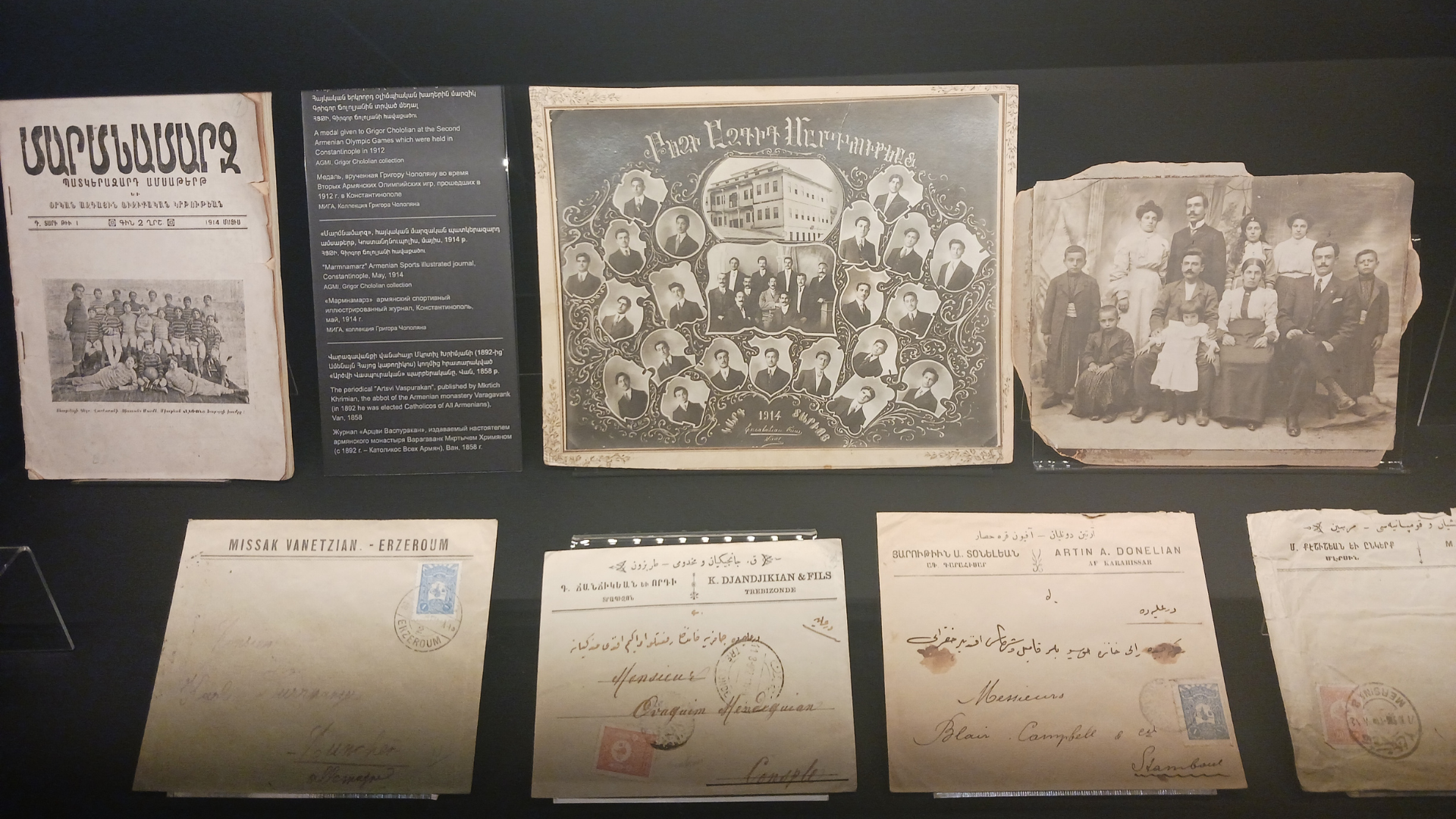

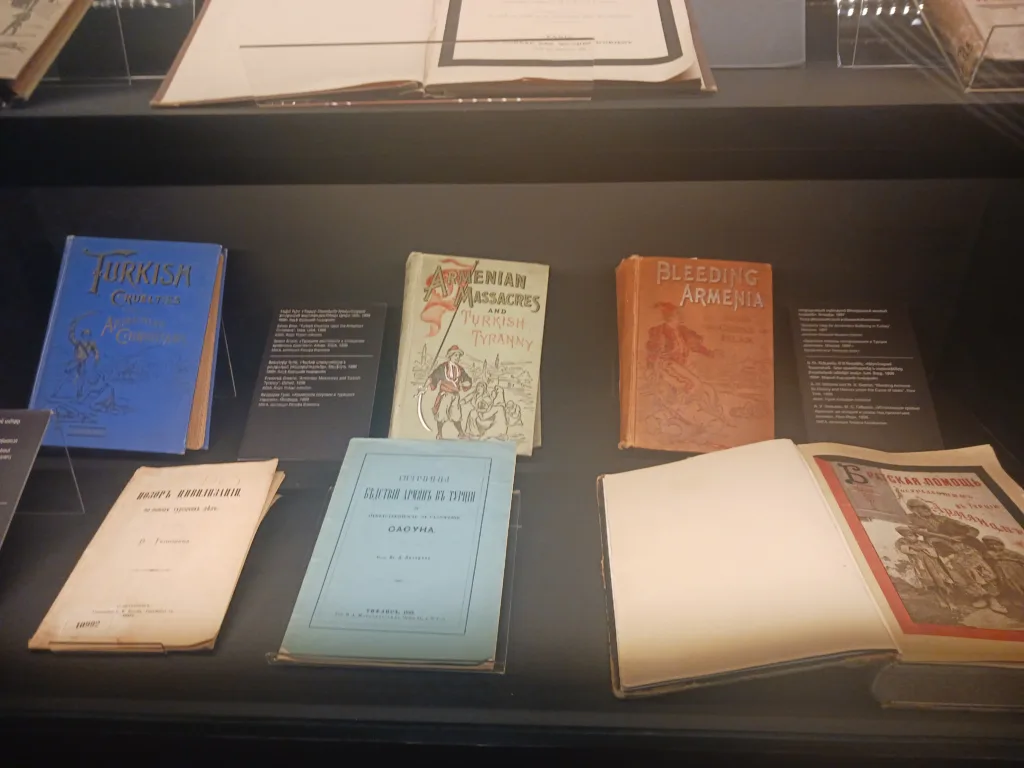

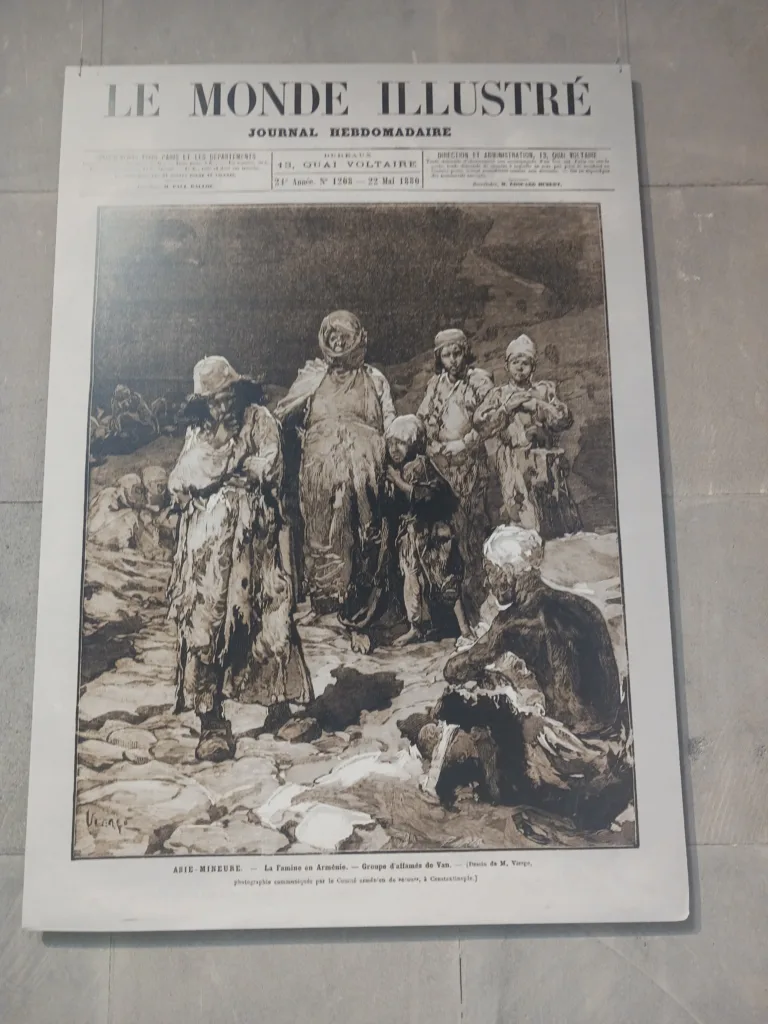

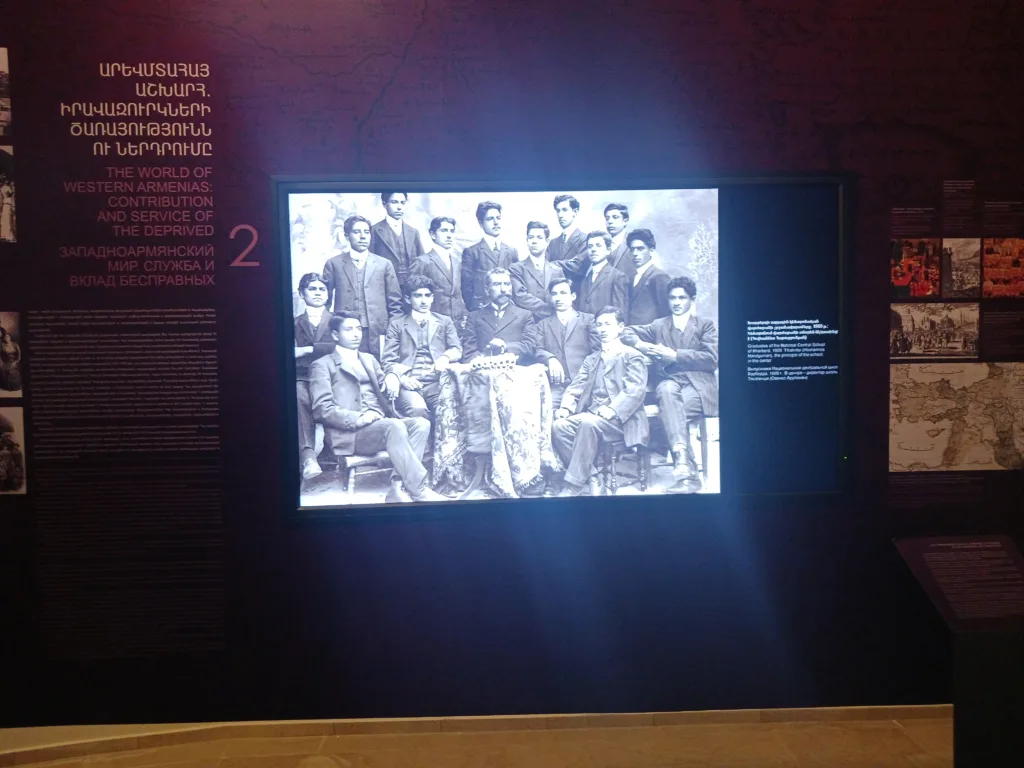

In the first room, the history of the genocide unfolded before me like a nightmare. Maps, dates, documents, all spoke of the rise of the Ottoman Empire and the barbarity that humans are capable of committing just to extend the influence of their power.

In a glass case, I saw a ledger full of names. It was the death list of a village, written in ink faded by time. Each name, a life extinguished, a family annihilated.

Next to it, an identity card, rusty and torn, as if violence aimed to erase even the identity of the victims.

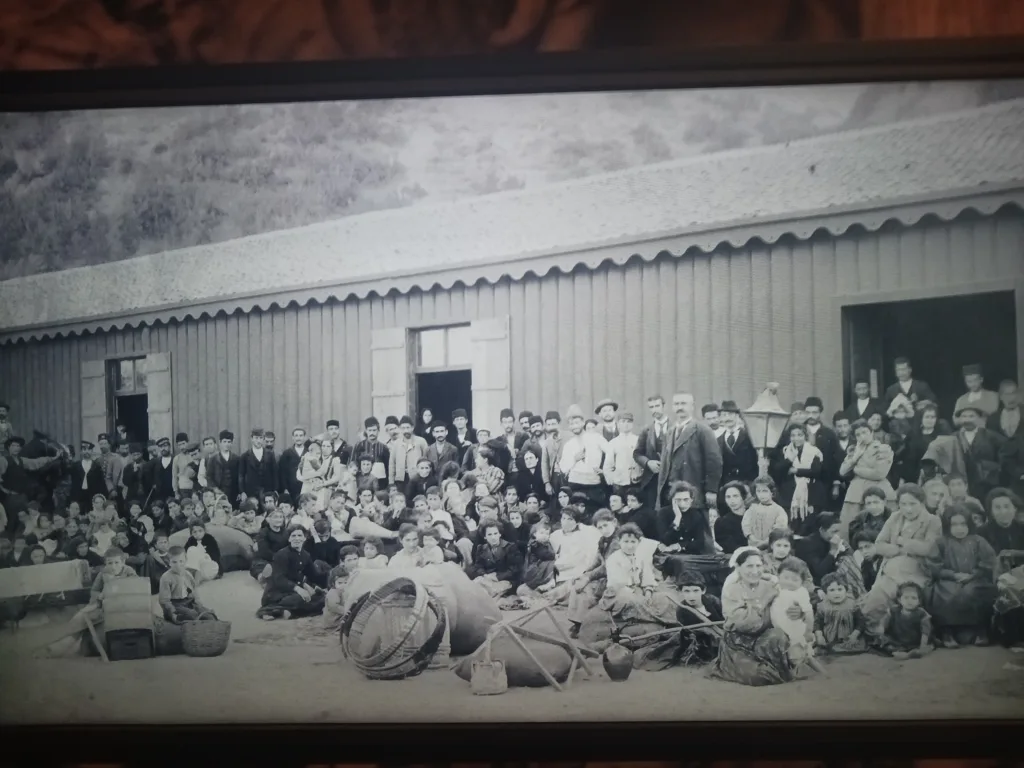

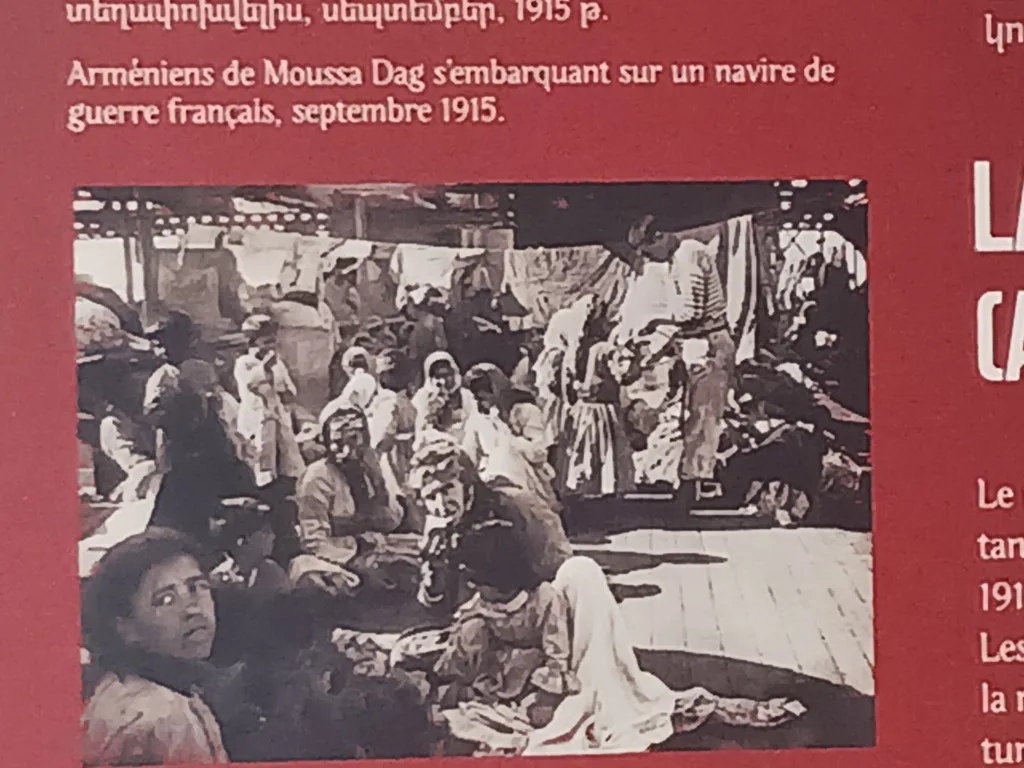

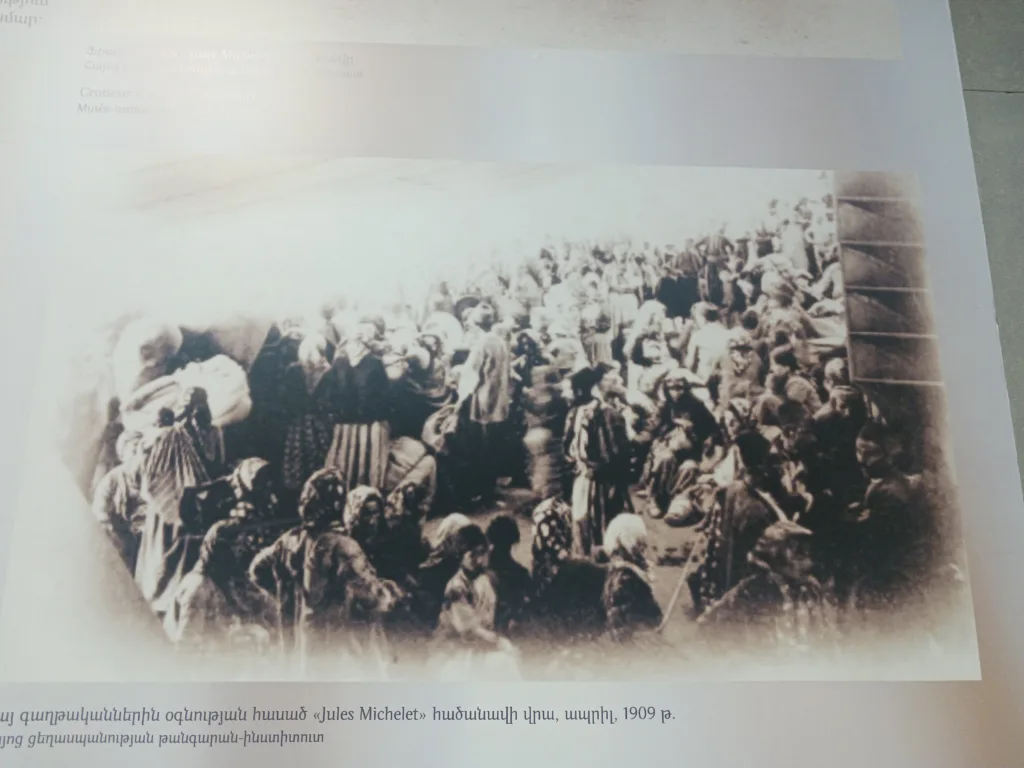

Moving on, I found myself in a room dedicated to atrocities. There, I saw photographs of massacres, looting, and rapes. I took some photos and observed the eyes of the other visitors who could not bear the horror.

In a corner, I stood before a showcase with children’s shoes. Tiny, worn, witnesses of lost innocence. Next to them, a doll with a broken arm, as if violence had touched even the children’s toys.

In another room, I saw personal belongings: watches that stopped at the time of the massacre, family photos full of smiles that had faded, letters from loved ones who never got to see each other again. Each item a story, a cry of pain, an unbearable testimony.

A ray of hope

In the last room, I saw a ray of hope. Where once death reigned, life now blossomed. Photos of survivors, stories of resilience and rebirth, testimonies of a people who refused to bend.

Everything passes, I thought as I left. Today, on the 19th of May, Pontians honour their Genocide Day. A similar story of horror. You could simply change the names from Armenian to Pontian and you would have the same lament, the same wounds that bleed.

But also the rebirth. Because, as the poet Dinos Christianopoulos says: “and whatever you did to bury me, you forgot that I was a seed.”

And so they blossomed again. The Armenians, the Pontians, the peoples who suffered barbarity and carry it with them, sometimes as a burden for their development, other times as a reminder of the sufferings of their ancestors, who gave them freedom.

Leaving the museum, I saw the Armenians with heavy hearts. But in my eyes, they seemed stronger. The wound still “bleeds,” but the memory lights the way to the future. They must not forget…