By Dr Themistocles Kritikakos (Historian)

In 706 BCE, Spartans arrived in what is now Puglia. They were not conquerors but exiles, cast out from their homeland. The Spartans established a settlement on the southern coast of Italy that would grow into the influential city of Taras (modern-day Taranto), named after the son of Poseidon.

The exiled founders, known as the Partheniae (“sons of virgins”), were the offspring of emergency unions between Spartan women and non-citizens (men considered to be of lower status) during the brutal Messenian Wars. Some sources suggest these unions were formed to maintain the population while the men were away at war. When these unions were later declared invalid, their children faced a choice: exile or rebellion. They chose exile, transforming their rejection into one of Magna Graecia’s success stories.

Taras: The rise of a Spartan city

Mythological accounts tell of oracle prophecies influencing Phalanthus, the divine hero, to colonise Taras. Tucked into the heel of Italy’s boot, Puglia, particularly around modern Taranto, stands as a testament to ancient Greek colonisation. While often overshadowed by the celebrated Greek sites of Campania, Calabria, and Sicily, this region nurtured flourishing Hellenic settlements that merged with local cultures.

Taras evolved into a maritime and commercial powerhouse, its position strengthened by the resolve of its Spartan founders. Situated between two natural harbours on the Gulf of Taranto, the city held a strategic position along important maritime routes connecting Greece, Sicily, and the wider Mediterranean. While Taras initially reflected Sparta’s military discipline and aristocratic traditions, interaction with local Italic tribes (the Messapii, Peucetians, and Daunians) created cultural fusion that merged Greek religious practices and artistic styles. By 500 BCE, the city had grown into one of Magna Graecia’s most significant and populous centres.

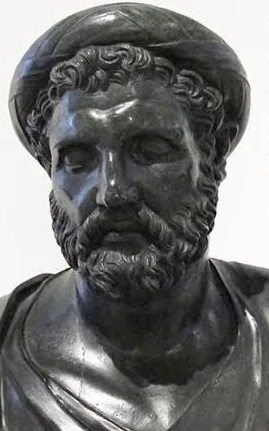

The city produced Archytas, a 4th-century BCE philosopher, mathematician, Pythagorean statesman, and military commander (strategos), whose pioneering contributions to mathematics and mechanics elevated Taras’ standing throughout Magna Graecia. According to tradition, Archytas saved Plato’s life by dispatching a ship to rescue him from the court of Dionysius II of Syracuse.

Artefacts in Taranto’s museum (pottery, jewellery, and terracotta figurines) reveal its vibrant material culture. Among the most prominent discoveries is the Tomb of the Athlete, where an Olympic victor was buried with his prize amphora and sporting equipment, demonstrating the city’s athletic prestige.

Though Rome eventually conquered Taras in 272 BCE following the defeat of Pyrrhus of Epirus, the city’s importance endured. During the Second Punic War (218-201 BCE), Taras again asserted its independence by allying with Hannibal, though this ultimately sealed its fate under Roman rule.

In the Salento peninsula, also known as Grecìa Salentina (Salentine Greece), at Puglia’s southern tip, this cultural persistence is tangible in the Griko dialect, still spoken in a handful of villages. This surviving dialect represents a living link to the region’s Greek heritage, although scholars debate whether its roots stem directly from the ancient Greek colonies of Magna Graecia or primarily from later Byzantine Greek influence. Griko demonstrates that the legacy of Magna Graecia is reflected not only in archaeological sites but also in living cultural practices. Today, as Taranto serves as Italy’s primary naval base, the importance of this ancient harbour continues, bridging its Greek past with its modern maritime role.

The Golden Grain: Metapontum’s story

Moving inland from Puglia’s coast, the neighbouring region of Basilicata also played an important role in the story of Magna Graecia. Founded by Achaean colonists around 720–700 BCE, the ancient city of Metapontum developed as an agricultural and trading centre, with its fertile plains producing the grain that sustained the city’s wealth. This economic success was symbolised by the ear of barley adorning its coins. Metapontum gained lasting fame through its association with Pythagoras, who spent his final years in the city around 500 BCE.

Metaponto’s Archaeological Park, featuring the famous Temple of Hera (Tavole Palatine), the theatre, and the agora, offers vivid glimpses into its rich Hellenic past. Although the city declined under Roman rule, its Greek cultural influence endured in the Byzantine monastic communities that later spread across Basilicata’s interior.

Across both Puglia and Basilicata, the interaction between Greek settlers and Italic peoples created a distinctive cultural blend. Religious worship, theatrical performance, and funerary art all reveal a creative dialogue between Hellenic and local traditions. Greek motifs (meanders, mythological scenes, and terracotta figurines) merged with Italic forms, leaving behind a rich material and spiritual legacy that archaeologists continue to uncover.

Puglia and Basilicata may receive less attention than Sicily, Calabria, and Campania, but they complete the mosaic of Magna Graecia. Together, these regions reveal a Mediterranean world shaped by exchange, where Greek settlers transformed southern Italy into a network of cities, sanctuaries, trade routes, and ideas. They remind us of Greek civilisation’s broad influence and how even exiles and outcasts could build cities that permanently shaped history, as the Spartans did in Taras.

Next Fortnight: Part 6 of the Magna Graecia series will bring the story to a close with a comprehensive overview, exploring the enduring legacies of Greek civilisation in southern Italy.

Links to the series:

Magna Graecia – Part 1: Hellenism beyond the homeland

Magna Graecia – Part 2: The Greek foundations of a new city

Magna Graecia – Part 3: Hellenism cast in bronze

Magna Graecia – Part 4: From Colony to Colossus: Syracuse and Hellenism in Sicily

*Dr Themistocles Kritikakos is a Greek-Australian historian, philosopher and writer. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Melbourne. His forthcoming book explores intergenerational memories of violence in the late Ottoman Empire, identity, and communal efforts toward genocide recognition, focusing on the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian communities in Australia.