On 28 October 1940, Greek leader Ioannis Metaxas refused Mussolini’s ultimatum to occupy Greece, an act of defiance now commemorated as Ohi Day (No Day). It was a moment defined by one powerful word — “No” — reminding us how language and names can shape national identity.

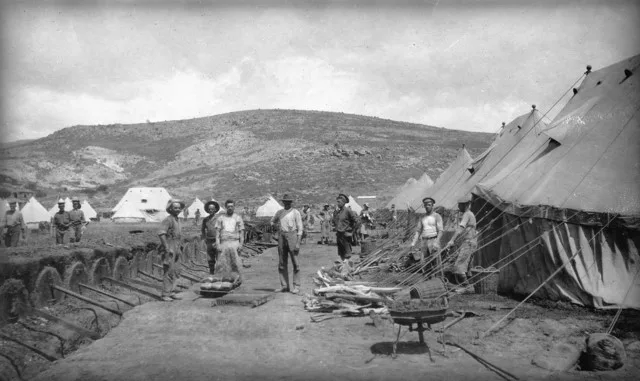

Around that same time, my maternal grandfather, Nicholaos Apistolas, from the island of Imvros (renamed Gökçeada), was conscripted into the Turkish army. His island, a naval base for the Allies during World War I, had aided the ANZACs at Gallipoli. By World War II, it was ceded to Turkey under the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, and its Greek inhabitants, like my grandfather, were forcibly classified as Turkish nationals.

In Constantinople, my paternal grandfather Theodore Sinanidis was adjusting to another imposed renaming, the 1930 law that made “Istanbul” the city’s official postal name. By 1942, it wasn’t just a matter of semantics, he lost a large part of his fortune through the punitive “wealth tax” targeting citizens marked as Rumlar (Romans) on their Turkish IDs.

My family were all Rumlar (Romioi) the Turkish name for Romans, used to obscure their Hellenic roots. Though they spoke Greek and practiced Orthodoxy, they were politically redefined as remnants of the Byzantine Empire, cut off from modern Greece. This reclassification dictated not only their citizenship but also their sense of self.

It is from this imposed label that my connection to Romiosyni, that thread of cultural endurance, was born. It continues to remind us: “We are still here.”

Yet, where we were was a kind of cultural no man’s land. Post–World War II, Turkish policies deepened the distance, while rejection also came from Greece itself. My mother recalls being called Tourkospori (Turkish seed) and hanoumaki (Turkish lady) while studying in Athens. The alienation came from all sides.

This struggle over names, imposed, reclaimed, and reinterpreted, lies at the heart of modern Greek identity. Of course, to outsiders, we are simply Greek.

As a word, ‘Greek’ was popularised by the Romans after encountering a small tribe called Graikoi. The irony endures: the nation that defied Italy on Ohi Day still carries the name bestowed by its Roman conquerors.

Professor Vrasidas Karalis, Modern Greek and Byzantine Studies Lecturer at the University of Sydney, notes that both words, Greek and Hellenic, carry emotional weight in different contexts.

“For Westerners, Greek is the name they came to know us as a nation since the Greek revolution. It resonates with a revolutionary past and the struggle for freedom,” he says.

Karalis adds it was a name cemented globally during World War II, following the spirit of the famous (if debated) expression: attributed to Churchill himself: “Heroes fight like Greeks and not Greeks as heroes.”

For Hellenes, Ellinas expresses continuity. Karalis points to Greece as a nation with many names: Graikoi, Yunan, Romioi, but a single essence. “We must not forget Athanasios Diakos, when killed by the Turks, sang: ‘Εγώ Γραικός γεννήθηκα, Γραικός και θα πεθάνω.’ (I was born Greek, and Greek I will die).”

“Names do matter,” adds Professor Joseph Lo Bianco, President of the Pharos Alliance. “But they’re context-dependent, think Burma versus Myanmar. Each name reflects a different era and power dynamic.”

He points out that languages and identities rarely align neatly: “We don’t say Deutschland in English; we say Germany. We once said Pekingand now say Beijing. The Finnish call their country Suomi. It’s all shaped by history and habit.”

Similarly, Turkey’s insistence on being called Türkiyesince 2021 was more than branding — it was linguistic sovereignty. “When Erdogan pushed for the change, the simplest reply would have been: Turkey is the English equivalent of Türkiye,” says Lo Bianco. “So why can’t we have Greece and Hellas?”

People who push to call our homeland Hellas instead of Greecepoint to this as an act of decolonisation, an accuracy when it comes to our identity. Lo Bianco says, “What a nation calls itself versus what others call it is steeped in power and struggle.”

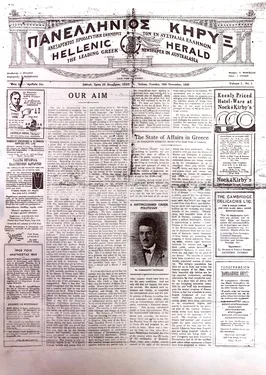

Councillor Helen Politis, founder of the Greek Australian Forum on Facebook, deliberately chose ‘Greek’: “I wanted to connect second, third and fourth-generation Greek Australians, and invite non-Greeks to engage in civic life.”

Father Armandos Manafis, administrator of the Hellenic Australian Forum, took another path: “Hellasmeans ‘land of light’, from Hel (light) and las (land). It speaks to enlightenment and resilience.”

The Hellenic Museum was aptly named thus to reach closer to the ideals of philosophy, democracy, and beauty that our ancestors cherished beyond Greece’s borders. “I think the notion of Greekness really depends on what period you are looking at,” Hellenic Museum CEO Sarah Craig told the Greek Herald in a previous interview. “The geographic borders have continually shifted over time so that is why we are the Hellenic Museum rather than the Greek museum.”

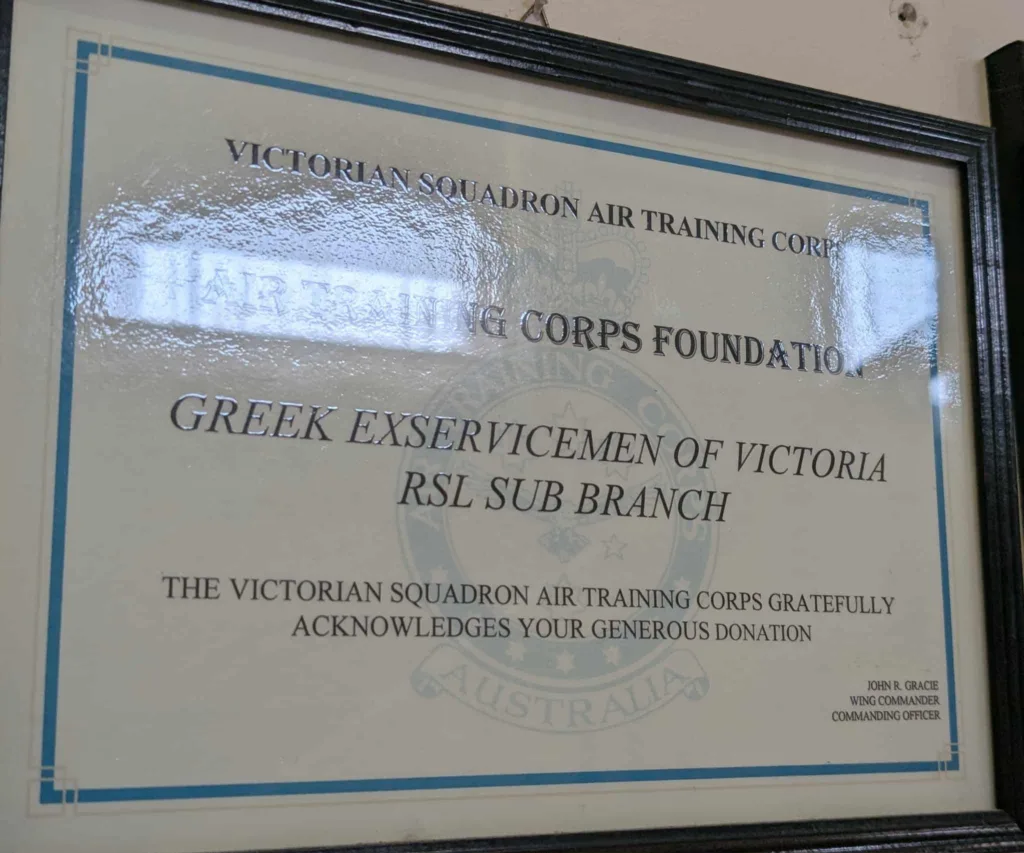

The Hellenic RSL chose its name to align with Greece’s armed forces — theHellenic Army, Navy, and Air Force. Secretary Terry Kanellos notes, “Even NATO uses ‘Hellenic.’ It reflects history and pride.”

Hellenic RSL President Manny Karvelas adds, “It’s inclusive of all Greeks from Greece, Cyprus, and the diaspora. Hellenic represents shared lineage beyond borders.”

During WWII, Greeks fought for Hellas, and I asked my grandfather what that meant for him, forced to wear a Turkish uniform at the time. Was he ashamed? He replied “No” because neither uniforms nor ID cards could define him.

He said he was Romios, guided by the flame of Romiosyni, burning with the same quiet defiance that answered “’Οχι’” in 1940. “Greek. Hellenes. Yunan. Romioi. Whatever name history gives us, we are still here.”