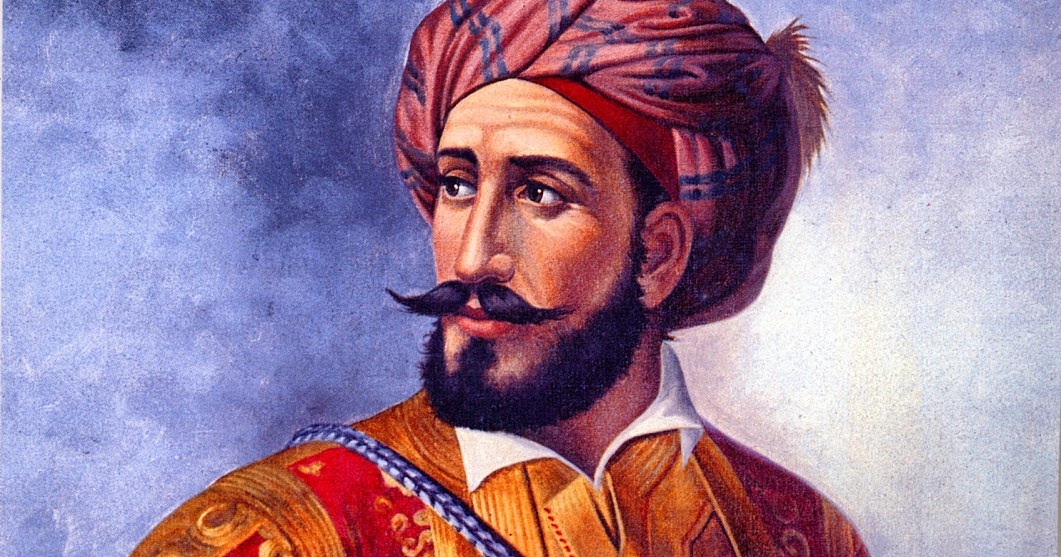

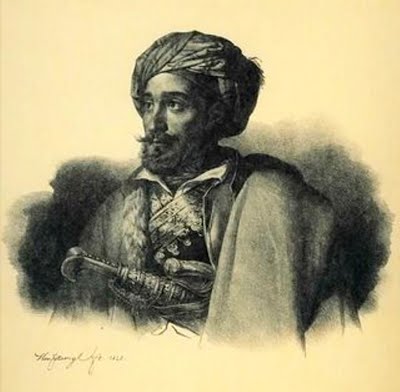

General Giannis Makriyannis is an important historical figure in Greece. People know him by many titles – Greek merchant, military officer during the Greek War of Independence and politician. But today, he is best known as the author of his Memoirs, which is considered ‘a monument of Modern Greek literature’ as it is written in pure Demotic Greek.

We’ve decided to look back at these impressive achievements to commemorate the death of Makriyannis on this day in 1864.

Early Life:

Giannis Makriyannis was born to a poor family in the village of Avoriti, a small village between Mount Oiti and Parnassus. His father, Dimitris Triantaphyllou, was killed in a clash with the forces of Ali Pasha. Makriyannis and his family were then forced to flee to Levadeia, where Makriyannis spent his childhood up to 1811.

At age seven, he was given as a foster son to a wealthy man from Levadeia, but the menial labour and beatings he endured were, in his own words, “his death.” Thus, in 1811 he left for Arta to stay with an acquaintance and became involved in trade which, according to his memoirs, made him a wealthy man.

Makriyannis joined the Filiki Etaireia, a secret anti-Ottoman society, in 1820 and decided to take up arms against the Ottomans under chieftain Gogos Bakolas in August 1821.

The Greek War of Independence:

Makriyannis’ most notable success during the Greek War of Independence has always been the defence of Nafplio in the Battle of the Lerna Mills.

For this battle on June 10, 1825, Makriyannis arrived in Myloi, near Nafplio, with 100 men. He ordered the construction of makeshift fortifications, as well as the gathering of provisions. Ibrahim Pasha, the commander of the Egyptian forces, was unable to take the position despite numerical superiority and the launching of fierce attacks on June 12 and 14. Makriyannis was injured during the battle and was carried to Nafplio.

Soon after the battle, he married the daughter of a prominent Athenian and his activities were thereafter inextricably linked with that city until his death. When Athens was captured by Ibrahim Pasha in June 1826, Makriyannis helped organise the defence of the Acropolis, and became the provisional commander of the garrison after the death of the commander, Yannis Gouras.

He sustained heavy injuries to the head and neck during the defence. These wounds troubled him for the remainder of his life, but they did not dissuade him from taking part in the last phase of the war: in the spring of 1827 he took part in the battles of Piraeus and the battle of Analatos.

Activities after Greek Independence:

After the war, Makriyannis worked with Greece’s new Governor Ioannis Kapodistrias. He was appointed ‘General Leader of the Executive Authority of the Peloponnese,’ based in Argos. But eventually, Makriyannis became disenchanted with the autocratic ways of Kapodistrias and, after refusing to offer what he considered to be a demeaning oath of loyalty, he was stripped of his command in 1831.

In 1832, Prince Otto of Bavaria was chosen as the first King of Greece. His arrival was hailed enthusiastically by Makriyannis, as he saw it as an opportunity to push for the creation of a new constitution. In the end, his efforts payed off as he became a key player in the formation of the constitution and a new cabinet.

While his story should have ended there, it did not. Enemies accused him of treason in 1852. He was tried, sentenced to death, put in prison for eighteen months, stripped of his military rank, and then pardoned in 1854.

Literary Work:

Makriyannis’ book Memoirs, written in Demotic Greek, was first published in 1907. In the text, one can see not only the personal adventures and disappointments of his long public career, but more significantly, his views on people, situations and events.

The work remained relatively unknown until the German occupation of Greece, when novelist Giorgos Theotakas published an article on Makriyannis and called his book “a monument of Modern Greek literature.” Theotakas believed the work not only reproduced the heroic atmosphere of the War of Independence, but was also a treasure-trove of linguistic knowledge concerning the common Greek tongue of the time.

Famous Greek poet, Kostis Palamas, also called his work “incomparable in its kind, a masterpiece of his illiterate, but strong and autonomous mind.”