ANZAC Day commemorates the date the Australian and New Zealand Army Corps landed at Gallipoli in Turkey on April 25, 1915, marking the first time the two armies fought together away from home for the noble ideas of freedom and democracy.

But what is the relevance of this to Greeks and Australians of Greek heritage?

The Gallipoli Campaign marked the beginning of enduring relations between the Greeks and Anzacs. During the Gallipoli Campaign, the Greek island of Lemnos became the headquarters of the battle, where ships were anchored, water and food was sourced, and hospitals were set up to look after the wounded. Only 25 years later, over 34,000 Anzacs returned to the Mediterranean for WWII and served with distinction in the Battle of Crete and the Greek Campaign.

To discuss this connection in further detail, The Greek Herald spoke with Nick Andriotakis, the Secretary of the Joint Committee for the Commemoration of the Battle of Crete and the Greek Campaign. This is what he had to say.

1. Nick Andriotakis, please tell us a little bit about the Joint Committee.

I am the Secretary of The Joint Committee for the Commemoration of The Battle of Crete and The Greek Campaign (Joint Committee). The Joint Committee is a non-profit organisation that is actively involved in commemorating the anniversary of the Anzac Battles of Crete and Greece for over 40 years. The Joint Committee was formed in the late 1970s by the Cretan Association of Sydney & NSW, the 2/3rd Field Regiment, the 6th Australian Division represented by Major General Sir Ivan Dougherty, Major General Ian Campbell, Major General Allan Murchison, Steve MacDougal, Bill Jenkins and Lew Lind.

The Joint Committee was associated with the: Federation of Naval Ships Association: Naval Association of Australia (NSW Branch); Ash eld RSL Sub-Branch and National Serviceman’s Association (NSW Branch) and the New Zealand Sub-Branch of the RSL. We have worked closely with The Returned Services League, the Department of Veterans Affairs, the Government of the Hellenic Republic, Anzac families and the community. In 1979, the Greek Sub-Branch of the RSL were invited to join the committee and in 1980, their secretary Evangelos (Angelo) Efstratiadis OAM became its chairman. In 2001, James Jordan, the current chair, accepted the position.

The Joint Committee’s aim is to commemorate the Australian men and women that served in 1940-1945 on the Greek mainland, in the Greek seas and later, on and around the Greek island of Crete. The Joint Committee honours the Australian and Greek servicemen and women and their Greek allies by keeping their memory and legacy alive and relevant to contemporary Australia and future generations. The Joint Committee hosts an annual wreath laying ceremony on the anniversary of these campaigns at Martin Place, Sydney, on or around May 20.

ANZAC is one of the most important aspects of modern Australian history. There were only two Anzac Corps – the 1st Anzac Corps being in Gallipoli in 1915 (used the Greek island of Lemnos as its headquarters, training grounds and hospitals), and then the 2nd Anzac Corps in Greece in 1941.

The Anzacs of Greece is an important Australian history that deserves to be known by all Australians and Greeks. Though it stands as the Second Anzac Campaign, the Battles of Crete and Greece are not so widely known and have been labelled the “Forgotten Anzacs.” Also, not so widely known is the participation and contribution in the Australian defence forces over the last 124 years of some 2,500 Australians of Greek heritage.

2. Can you describe your Cretan heritage and the influence of Anzac Day on you?

I was born in Crete and migrated to Australia with my family when I was six years old so therefore, my ancestors are all from Crete. However, I would like to share a story about the Australians that fought in Crete and how their experience influenced me.

When I was growing up in Sydney there were many Anglo-Celtic Australian families who attended the Cretan dances or socialised and visited Cretans in their homes and vice versa. The fathers of these families had fought in Crete and some of them were saved by the Cretan people until they escaped or were eventually captured by the Nazis. Some of them could even speak Greek. Meeting these families over time instilled in me a pride of being Greek for what the Greeks did at great risk to their lives to save and protect the Australians, but also an admiration at the Australians for fighting in the defence of Greece and how they and their families wanted to maintain this bond with the Greek people in Australia so many years later.

When I was about 18 years of age, I was in the Cretan Dancing Group of the Cretan Association and we were told that we had to march in our traditional Cretan costume on ANZAC Day, the most important day for all Australians. On this ANZAC Day, like so many before, the veterans put on their suits and proudly displayed their service medals and marched with their fellow soldiers and family within their own military unit association. Out the front, they had their standard (flag) and many had Greece or Crete as places of service. The streets were lined with tens of thousands of people to applaud and commemorate these war heroes.

As we assembled at the beginning of the march route, one man in a suit and wearing his medals, called out to me in confident yet playful Australian slang, “You’re from Crete, aren’t you son?” to which I replied rather softly, “Yes sir.” He then said, “Come with me lad and stand next to me and march with me.” So I went over and stood next to him – after all, that is what we were supposed to do – march.

One of the organising security marshalls saw this and came over and said to me, “Sorry son, you cannot stand here,” to which the Anzac interjected, “Why not mate? The boy is marching with me.” At this point the marshall explained that I had to go to the back and march with all the other ethnics (immigrant groups). The Anzac looked at him fiercely and said, “Mate, these people saved my life and the boy is marching with me!” A verbal argument broke out but eventually rules are rules and I did go to the back with the ethnics.

That experience never left me and the facts have stayed with me vividly. With time, maturity and wisdom some thirty years later, after I had my own children, I wondered what would be the relevance of any of the legacy of a “Greek-Australian” for a new Australian generation? How relevant or what does it mean to be an Australian of a mixed Greek heritage? Are the classic stereotypes of migrant workers, milk bars and fish and chip businesses going to be the main things that will define us?

I thought about that unknown Anzac on Anzac Day. I realised that he was fighting for Greeks in 1941 and it dawned on me he was still fighting for them through me, a young immigrant kid, some nearly 40 years later on Anzac Day in Sydney. That epiphany made me join the Joint Committee and inspired me to fight for all these unknown veterans, many of whom had passed away. Why was their service in Greece not that well known in the wider community? What was it that created this special bond? To answer these questions, I thought one had to get involved in an underdog situation and go from there.

So my aim was to learn a lot more and be able to educate and honour that unknown Anzac and his brothers and sisters through the collective commemoration of all the Anzacs of Greece and Crete, so that the legacy of the bonds of the Anzacs and the Greek people in Greece during WWII and post-WWII are not forgotten but are made relevant in the future for all Australians.

This quote from Paul Kougias of the Joint Committee sums up exactly why the Anzacs of Greece is relevant and guides the Greek Australian narrative:

“ANZAC’s of Greece projects on the surface are about ensuring the legacy of the ANZAC spirit in Greece is not forgotten. From the staging of the Gallipoli campaign on Lemnos Island during WWI to the dogged resistance of the Nazi invasion of Greece that inexorably turned the tide of WWII, Australia and Greece share a history of strength and dignity against incredible odds. The sacrifices made by the youngest democracy in the world defending the oldest democracy should not be forgotten.

At its core however, these projects are also about the ongoing journey of a migrant community to define its story of what it means to be Australian. The offering of its home country’s culture through food and entertainment were the first few steps, but it’s the shared stories of heroism & courage of the ANZACs of Greece that has the strength in narrative to bring forward a deeper meaning in what it means to be an Australian of Greek heritage and further enhance the already successful Australian multicultural story.”

3. According to historians, the strong alliance between the ANZAC’s and Greece goes back to the First Anzac Campaign in Gallipoli during WWI. Some 87 Australians of Greek heritage fought in this campaign and later in Crete and Greece in WWII, earning the name ‘dual ANZACs.’ Can you tell me a little bit more about these men?

In fact, the military alliance between Australians and Greeks begins with Australians of Greek heritage serving with the colonial forces in the Boer War in South Africa (1897-1900).

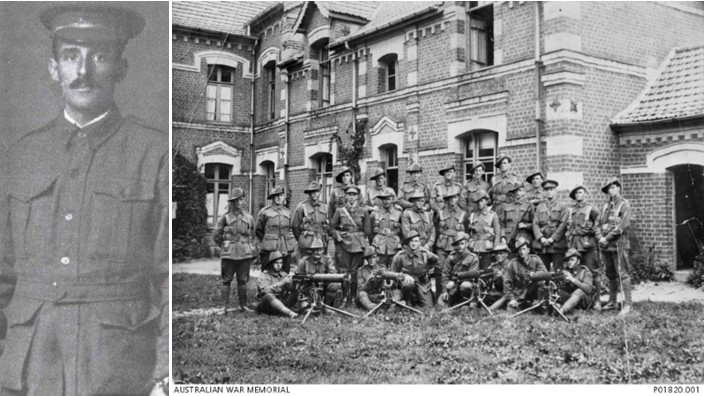

In WWI, over 100 Australians of Greek heritage served in the first Anzac Campaign on Gallipoli and later in Western Europe. One of these, Peter Rados, was killed in Gallipoli, having been born as a Greek in the nearby Turkish town of Erdek. He migrated to Australia, enlisted in the army and ended up in Gallipoli.

Over 2,400 Australians of Greek heritage served in WWII and many served in Greece in the second Anzac Campaign.

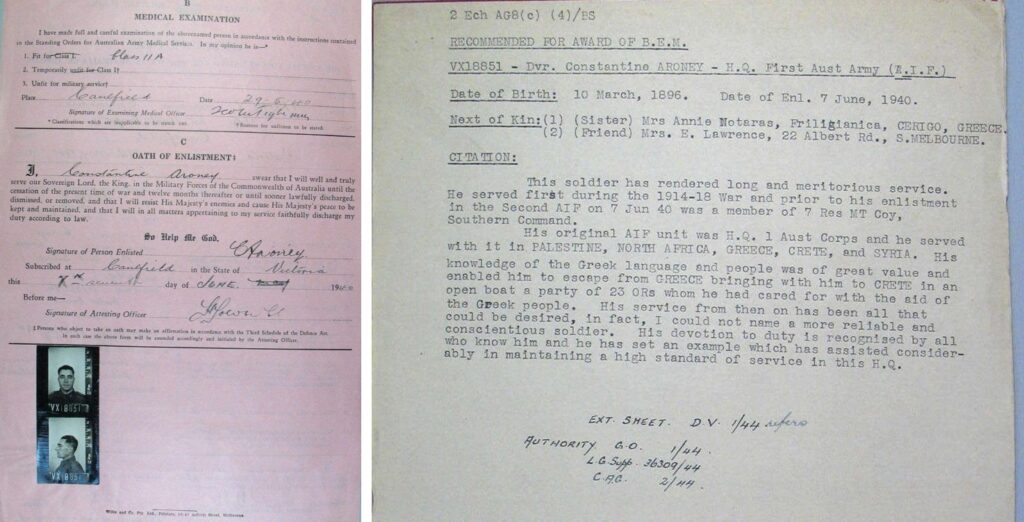

After serving in WWI, in the 1st Anzac Corps in Gallipoli, veteran Constantine Aroney enlisted and served in the 2nd Anzac Corps on mainland Greece and Crete. He is a rare ‘Dual Anzac.’

Mr Aroney was born in Kythera in 1893 and at the turn of the 20th century, he came to Australia and was living in Melbourne. He served Australia in both World Wars, enlisting in the First Australian Infantry Force in 1915 at age 20 years and 11 months. He served as a private in the First Anzac Campaign at Gallipoli and then onto France and Belgium as part of the 24th Battalion. In October 1939, he enlisted in the Commonwealth Military Forces and seven months later, he transferred to the 2nd Australian Imperial Forces, serving in the second Anzac Campaign in Greece and Crete, as well as Syria, Palestine and North Africa. While serving in Greece, Aroney’s cultural background proved extremely valuable with his knowledge of the Greek language and customs. Following the debacle on mainland Greece, when the Allied forces were overrun by the German army, Aroney managed to escape to Crete in an open boat, taking 23 Anzacs with him, whom he cared for with the help of Greeks on Crete – a heroic feat for which he was awarded the British Empire Medal.

Probably the most decorated Greek Australian in WW1 was Sergeant Nicholas Rodakis MM, DSC (US), AIF. Mr Rodakis was born in Athens in 1880 and enlisted in the First AIF in February 1916. He fought in the Western Front and was attached to a United States army unit, and in September 1918, Rodakis’ platoon was cut off behind enemy lines. As the unit fought to survive, Rodakis rescued an American officer in no-man’s-land before capturing a German machine gun. He then defended his position for hours, before returning to the allied lines under cover of darkness, picking up wounded as he went. For his actions, Rodakis was awarded the Military Medal and the United States Distinguished Service Cross – the American equivalent of the Victoria Cross.

4. The Greek island of Lemnos also became the headquarters of the Gallipoli campaign on 4 March, 1915. What was the importance of this island to the Anzac campaign?

Greece was a neutral country in the early part of WWI due to the disagreement between King Constantine, who favoured neutrality, and the pro-Allied Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. However, they did allow the British to use the island of Lemnos for the Gallipoli Campaign. Finally, Greece united and joined the Allies in the summer of 1917.

During the first Anzac Campaign in Gallipoli, the Greek island of Lemnos played an important strategic and operational role. Moudros Bay was large enough to harbour the vast British and French naval fleets and the island was used for obtaining supplies (including the famous donkey known as Simpson’s Donkey), training grounds and temporary tent hospitals, and to bury those that could not be treated and died.

The role of the Australian nurses was very significant and not as well noted as the role of the Anzacs in the Gallipoli Campaign. Moudros’ importance receded, although it remained the Allied base for the blockade of the Dardanelles during the war. In late October 1918, the armistice between the Ottoman Empire and the Allies was signed at Moudros.

From my perspective, Lemnos was the last place of normality for the Gallipoli Anzacs, the last place of peace, fresh water, clean air, bright sunshine, fresh brewed coffee, a Greek meal – all before the horrors of the Gallipoli Campaign. Lemnos was the last paradise. After they left Lemnos for Gallipoli, the lives of the Anzacs had changed for ever and so did Australia. Many of the wounded from Gallipoli were treated at the hospital base on Lemnos and some 250 Anzacs died and lie on Lemnos in the two Commonwealth cemeteries at Portianou and Moudros.

The town of Lemnos, Victoria, Australia, established in 1927 as a soldier settlement zone for returning First World War soldiers, was named after the island.

5. What was the role of the Anzacs in Greece during WWII?

Every year on October 28, the Greek people, including the diaspora, commemorate ‘OHI’ (NO) Day – the anniversary of the historic response of Greeks against Nazism, Fascism and Totalitarianism in WW2. On October 28, 1940, Greece said ‘NO’ to an Italian Fascist invasion and pushed them back and gave the Axis Powers their first defeat. This victorious defence destroyed the notion of Axis invincibility and gave hope to a battered and suffering world.

However, the result for Greece saying ‘NO’ created one of the most devastating impacts on any country in Europe. During WWII, Greece lost 11 percent of its population due to military conflict, civilian resistance, crimes against humanity and war resulting in famine and disease. Greece lost 80 percent of its Jewish population.

As a result of OHI and the Greek victory against the fascist Italians, the Nazis invaded Greece and consequently, the Allies came to its aid. In early April 1941, the Second Anzac Corps was established in Macedonia and followed the earlier victorious Australian naval engagements in Greek waters by HMAS Sydney in the Battle of Spada and HMAS Perth in the Battle of Cape Matapan. Greece, with the support of the ANZAC and Commonwealth Allies, resisted for over 210 days the invasion of the Axis forces. This resistance has been sighted by military leaders and historians as taking up valuable Axis power resources and delaying the Nazi invasion of Russia into a cold and harsh winter. The defeat of the fascist Italians and the delay of the Nazis in Greece is acknowledged as turning the tide of victory in the favour of the Allies.

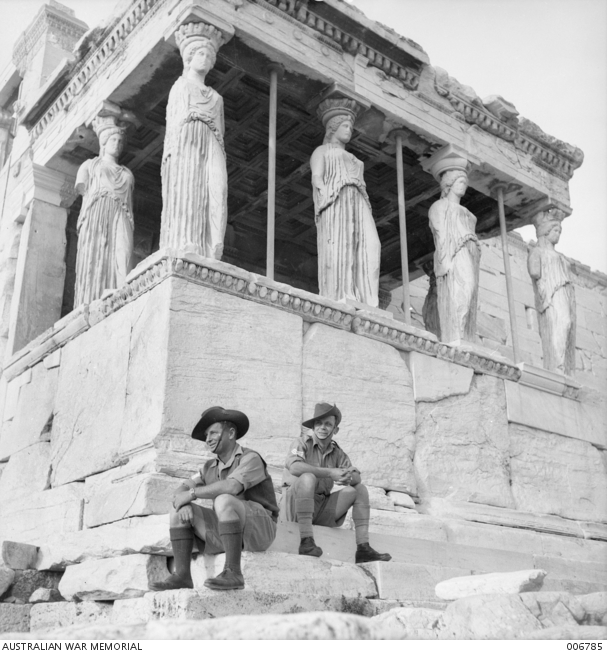

The Second Anzac Campaign in Greece and Crete involved a second generation of Anzacs adding fresh pages to the history of their forefather’s service some 26 years earlier in the Dardanelles. Together with the Greek people, the Anzacs confronted overwhelming odds with determination and the Anzac ideals of courage, mateship and self-sacrifice. In 1941, over 34,000 Anzacs fought in Greece and about half were Australian. They fought and walked nearly 1,000 kilometres of Greece’s mountainous terrain and engaged in the Battles of Vevi, Tempe, Thermopylae/ Brallos and finally, in the Battle of Crete.

Of the 17,000 Australian soldiers, airmen and sailors that served in Greece, 1,001 were wounded, 5,174 taken prisoners and 646 now rest in the Commonwealth War Graves at Phaleron (Athens), Rhodes and Suda Bay, Crete. Most people are also unaware that 83% of 6,203 Australians captured in the Second World War came from the Greek and Crete campaigns.

6. What was the feeling in Greece at the time of the arrival of the Anzacs?

The Anzacs were greeted with enthusiasm as defenders and liberators of Greece and the roads in Athens were covered with the flowers thrown at them in their honour. Unlike other Commonwealth forces, the Anzacs had an egalitarian ethos with no class distinction, and this endeared them to the Greek people. Generally, negotiations with the Greek villagers were amicable however, there was minor fifth column of Greek spies that were Nazi sympathisers. But the significant majority of Greeks refused to bow to the Nazi superiority and this impressed the Australians.

7. How would you describe the relationship between the Anzacs and Greece during WWII?

The significant majority of Greeks supported the Anzacs after the Nazis had overrun the country and they were welcomed as liberators and defenders of Greece.

During the battles, the Anzacs defended many Greek civilians caught in the crossfire. Later, after the war was lost and many Anzacs had escaped into the mountains of mainland Greece and Crete, they were fed, clothed and hidden by the Greek people. However, a tiny minority of Greeks were Nazi sympathizers and would reveal to the Nazis this support of the Anzacs and many Greeks suffered. In addition, many Anzacs felt guilty at this suffering and many were also captured and became Prisoners of War (POW). This guilt and the experience at being POW’s never left them and created a silence in their lives after returning to Australia. They just would not talk about the atrocities seen in Greece and the conditions of being a POW.

A 90-year-old Cretan was asked a few years ago why he protected the Anzacs at great risk to himself and his family and he said, “And? So what? They came from far away to defend us, defend our freedom, democracy and all for the love of their country.” Another Cretan was asked how he felt when his house was burned by the Nazis after helping Anzacs. He replied, “The burning of our family home was our proud contribution to the war effort.”

The Tzangarakis family of Rethymno supported Australia’s First Indigenous Officer, Captain Reginald Saunders, with food and shelter for months.

Many of the Anzacs believed what they were doing was just and had great respect for Greece and its people. Anzac Reginald Tresise had a lot of respect for Greece being the only nation in Europe helping the Allies fight for democracy.

My experiences with Anzac Dick Plant and his family also reveal how the experiences of the Anzacs laying their down their lives for the defence of Greeks and the Greeks reciprocating by supporting them at a large potential personal cost of losing their lives and their property, is a very special bond based on courage, philotimo and philoxenia and that it continues to affect the next generations and this really deserves to be always remembered.

On a brighter note, there were [also] some romances between Anzacs and Greek women and they married after the war.

8. There are so many tales of bravery from both the Greeks and Anzacs during WWII. Can you tell us which one stands out for you the most and why?

Constantine Aroney [who is described above] and General Paul A. Cullen DSO who served with bravery and distinction in World War II in the Battles of Greece and Crete [to name a few].

Captain Reginald Saunders:

Anzac Captain Reginald Saunders, Australia’s highest decorated Indigenous serviceman, was supported by the Tzangarakis family from the village of Labini in Rethymno prefecture. He evaded capture on Crete for almost one year until he finally escaped to Egypt.

Captain Saunders served Australia even though Australia did not allow him and all Indigenous Australians the right to vote until 1967. Outside the army he was considered a second-class citizen, but in the army he earned the respect of all his men. The Cretan people saw him as a fellow human being and risked their lives to support him. Captain Saunders later served Australia again in New Guinea and in the Korean War.

On November 11, Remembrance Day 2015, Captain Saunders was honoured at the Australian War Memorial with a new gallery bearing his name. It was the first time a room at the National War Memorial was named after a person. The ceremony was witnessed by his extended family and members of the Cretan and Greek communities. In May 2016, the 42nd Street Memorial plaque was unveiled in Chania, Crete, to commemorate the Battle of 42nd Street. Captain Reginald Saunders fought in this battle along with the Maori Battalion, who performed a haka before the onslaught against the Nazis. The Saunders family, along with journalist Michael Sweet and private donors from the Greek Australian community, have been instrumental in the creation of this memorial.

Sergeant Richard Tanner MM:

Sergeant Richard Sydney Turner was born in Sydney in 1916. He enlisted on October 28, 1939 and served with 6 Division Supply Column, Australian Army Service Corps. After service in Africa, he was captured by the Germans near Megara during the Greek Campaign in June 1941 but escaped from the train taking him to Germany between Lamia and Levadhia.

He was initially sheltered by the Greeks but this became too dangerous when Italian troops offered large rewards for the capture of Allied soldiers and threatened to shoot anyone harbouring them. Turner and a companion hid in the mountains south of Thessaly during the winter of 1941-1942. Weak from malnutrition and malaria, he was considering giving himself up when he met Ioannis Kallinikos from the village of Livanatas, who sheltered him for the next year and a half.

Turner joined the Greek resistance in the summer of 1943 and led a band of fifty Greek andartes (guerrillas). He later joined the British Military Mission in Greece (Force 133), which operated behind German lines. He was awarded the Military Medal for his endurance and service in Greece. In tragic circumstances, Turner was killed by Greek communist insurgents, during the civil war which broke out in Greece following the withdrawal of the Axis forces on 17 December 1944, while in a truck on his way to Athens airport to be repatriated to Australia.

Anzac Reginald Tresise:

[Author’s note] In Dr Maria Hill’s book, Diggers and Greeks, it is described how after withdrawing from Florina in northern Greece and sheltering in a schoolroom in the town of Kozani, Reginald Tresise noticed a Greek flag amongst the rubble of the bombed classroom. He rescued the flag and many years later, wrote a moving letter to the Mayor of Kozani about why “as an Australian soldier who has faith in Greece as a staunch ally of Western Democracies and especially of our British Commonwealth,” he wanted to return the flag.

Greatly touched by the letter, the Mayor replied and after Tresise sent the flag back to Kozani, the Mayor held an official ceremony at the school to “restore” the flag to its rightful place. Anzac Reginald Tresise was one of many Australian soldiers fighting in Greece who strongly believed that they were there to defend democracy against fascism.

9. Is there anything else you’d like to say?

Australians and Greeks have been interwoven for more than a century as solid, dependable allies and friends. Since the South African War (1899-1902), when Greek Australians fought in the Boer War, Australians and Greeks have been allies in all major world conflicts defending democracy, freedom, the rule of law and human rights. Both countries were involved in conflicts large and small, most famously the Anzac Campaigns of World War I and World War II. About 2,500 Australians of Greek heritage served Australia in WWI, WWII, Korea and Vietnam.

Some 1,686 Anzacs from both world wars lie in Greece and of these, nearly half were never found or their remains identified. They all now rest amongst their friends, comrades and their Greek allies in this ancient land.

OHI DAY is a much more relevant historical connection to all Australians than any other Greek Commemoration Day.

The fact that Greeks said ‘NO’ to the passage of the Italian Army on October 28, 1940, resulting in the defeat of the Italians and the first defeat of the AXIS powers in WWII, triggered a series of events. These events included the Nazi invasion of Greece which was the catalyst for the defence of Greece by the Second Anzac Corps and other Commonwealth units. The final result was a destroyed country with 11 percent of its people dying from starvation, war, executions and disease. After the war, politically, financially and physically wounded with regards to its infrastructure and institutions, Greece could not support its people. Hundreds of thousands of Greeks migrated to Australia and other places.

In summary, OHI day is the genesis of the Anzac involvement in Greece in WWII and the consequences resulted in the post WWII migration of Greeks to Australia and other places. It is important to acknowledge, commemorate and honour this historical and unique tie OHI has resulted between Australians and Greeks.

The Anzac legacy and OHI day should continue to be commemorated remembered with honour by Australians and Greeks around the world. 2021 represents the 80th anniversary of Anzacs in the Battle of Crete and the Greek Campaign and also the bicentennial of the Greek War of Independence. The story of Anzac Reginald Tresise and the Greek flag as described is really relevant here.