By Haris Tsioupas, MSc, Aristotle University Thessaloniki, and Lazaros Spiropoulos.

Macedonian struggle:

The aspirations of foreigners, mainly Bulgarians and Serbs for our Macedonia, led to attacks from time to time. The Bulgarian attacks against the Greek element of Macedonia began after the establishment of the Bulgarian Exarchate in 1870, and intensified from 1900 after the unfortunate war of Greece with the Turks in 1897 in Meluna of Thessaly. The Supreme Council of the secret Komitatos [Italian word: guerrilla or revolutionary organisation], was convened by the Bulgarians which pursued certain purposes, with terrorist acts, with the aim of Bulgarizing Macedonia.

Thus began the Macedonian struggle during which, the Greek element of Macedonia, then aided by the hesitant – then fearful Greek Government, took up the defence against the Bulgarian plan, whose propaganda and actions exceeded all limits with funding – blackmail – executions, etc.

However, the first reaction from the Greek side, against the Bulgarian Komitatos, manifested itself in 1903. Ion Dragoumis (1878-1920), who was serving at the time, at the Greek Consulate in the Monastery (now Bitola) area of Skopje, together with other Macedonians, formed a committee of patriots, which, immediately, created two corps of Macedonian warriors led by the captains Vangelis and Kottan from the province of Kastoria.

Similar actions were then taken by the hitherto hesitant government of Athens, with the dispatch of a few officers and soldiers led by Pavlos Melas [1870 – 1904, born in Marseille, France], which had immediate results. The contribution of the leaders and men of the Macedonian struggle, which lasted until the summer of 1908, was great in terms of the advance of the Greek army in 1912 in Macedonia and its liberation.

Ion Dragoumis, born in Athens (1878-1920), was the son of Stefanos Dragoumis who served as Prime Minister of Greece in 1910. The family was originally from Vogatsiko, Kastoria.

He was murdered in 1920 at the age of 42, by men of the “Special Security Companies” of Pavlos Gyparis, a well-known Macedonian fighter, trusted and ardent supporter of Eleftherios Venizelos.

Hellenism was thus deprived of a man who combined beauty, education, selflessness, writing talent, diplomatic intelligence and vision.

Ion, who said that freedom is conquered, is not given away by others.

Ion, who said to the then-reluctant Greek Government after the defeat at Meluna in Thessaly in 1897 by the Turks: “Know, that if we run to save our Macedonia, Macedonia, the shield of Greece will save us. If we run to save our Macedonia, we will be saved”

The first Balkan War began in October 1912 in which Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro engaged in a war with Turkey, a war that ended with the signing of the Treaty of London on May 30, 1913. As a result, Turkey renounced all claims to Crete, but the status of the Aegean islands was not determined.

Greece was organised into a state during the reign of King George I [(1845 – 1913) – (king from 1863 – 1913)]. He was assassinated in Thessaloniki on March 18, 1913.

The Second Balkan War (in 1913) began with the attack of Bulgaria against Greece and Serbia, Bulgaria was defeated and then Romania joined the war, against Bulgaria, due to a dispute over the Dobrudja region on the Danube River.

The Second Balkan War ended with the Treaty of Bucharest, signed on July 26, 1913. With this treaty, Greece took Eastern Macedonia and its borders reached the Nestos River, while Romania captured Dobrudja from Bulgaria on the Danube River.

Dobrudja arranged for the ceding of its southern region to Bulgaria, something that to this day causes friction between the two countries.

World War I (1914–1918) began on July 28, 1914, with the assassination of the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand and his wife in Sarajevo on July 28, 1914, and the attack of Austria against Serbia that followed.

The war ended on November 11, 1918, with a victory of the Triple Alliance [Entente – i.e., England, France and Russia) and their allies, Greece, etc., against the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary and their allies, Turks and Bulgarians. The end of the First World War found Greece counting its wounds.

Battle of Skra: In the battle on May 17, 1918, the Greek army, with heavy losses of 4000 dead, crushed the Bulgarians in Skra Kilkis, which the Bulgarians had captured in the spring of 1916 and had held with the support of the German forces.

The Treaty of Neuilly was signed on November 27, 1919, in the town of Neuilly sur Seine in France. With this treaty, Bulgaria was obliged to return Eastern Macedonia and Western Thrace to Greece, from Nestos to the Evros River, which had been occupied by the Bulgarians and their allied German forces in August 1916. The final annexation of the region to Greece was ratified by a special treaty ‘on Thrace’ signed in Sèvres on 28 July/10 August 1920. This treaty also provided for the voluntary exchange of Greek and Bulgarian populations.

Eastern Rumelia: It should be noted that the Bulgarians, in 1885, took the then-autonomous Eastern Rumelia in a coup d’état within the Ottoman Territory, a coup d’état that was recognised by the Treaty of Constantinople.

With the Treaty of Peace in Paris on January 21, 1920, the Smyrna Zone remained under Greek control. It should be noted that after the decision of the Allies on April 23, 1919, the Greek army, from May 2, 1919, landed in Asia Minor with approval – order of England and France, to prevent the occupation of Smyrna by Italy, and that’s when the Asia Minor adventure began.

The decision for the Greek presence in Smyrna, which would have been temporary, was more of an initiative of Britain, which wanted control of the Straits in the Hellespont, and by the Greeks, after the anti-war climate that prevailed in their country, as well as in France, from the great losses of the First World War. Faced with a strong internal anti-war climate in their country, the British and French made it clear that they would not help Greece militarily, which had to impose on its own the terms of peace that would be set with Turkey. Something that was accepted by Eleftherios Venizelos, who mistakenly believed that Greece could do it.

Despite the efforts of Eleftherios Venizelos, in 1919, none of the Greek claims had been realised.

With the inter-allied conference in San Remo, Italy, it was decided that the Greek Government would undertake to exercise the sovereign rights of the Ottoman state in the wider region of Smyrna for a five-year period, after which the fate of the region would be definitively decided by referendum. This arrangement was immediately opposed by the British high commissioner in Constantinople, Admiral John de Robeck, and Lord Corzon, saying that the Turks would resist.

On the night of 14th to 15th July 1920, Kemalist forces attacked a British battalion in the area of Nicomedia. Concerned about the security in Constantinople and the Hellespont Strait, Field Marshal George Francis Milne asked for reinforcements.

The inter-allied conference, which met in Boulogne, France, asked Greece for military assistance and addressed Eleftherios Venizelos. The Greek Prime Minister took the opportunity and offered a division. In return, approval was given on June 9, 1920, for the advance of the Greek army in Asia Minor. After the occupation of areas beyond Smyrna, such as Bursa (on June 25, 1920 ) and up to the Sea of Marmara in the Propontis, with the retreat of the Turks of Kemal Ataturk, the Treaty of Sèvres was signed, on July 28 / August 10, 1920.

With this treaty, Turkey was limited to Constantinople and a small area extending as far as the suburb of Catalta, which was a mistake as it turned out later. The remnants of the Ottoman state should then become a continental Turkish state, with no way out to the sea.

The rest of Eastern Thrace, as well as the Vilayet of Smyrna, was awarded to Greece, while Greek sovereignty was recognised in the islands of the Eastern Aegean, Tenedos and Imbros [the birthplace of the current Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople, Bartholomew].

With the Treaty of Sèvres, the Ottoman Empire was dismantled and then, among other events, the Great Greece of the Five Seas was created.

This policy, however, depended on the fate of the Hellenism of Thrace and Asia Minor, on the then dispositions of the great powers that acted on the basis of their interests: the big powers pressure whoever they want while they caress for their interest whoever they want, as is now the case with the aggression of Turkey in the Eastern Aegean. With the Treaty of Sèvres (28 July/10 August), Armenia gained its independence and Kurdistan a right to autonomy. At that time, France was taking the Adana region and the sovereignty of Syria. Italy, the Dodecanese and Libya. While England, part of Iraq Mosul, Palestine and Cyprus.

Cyprus, which by an article of the Treaty of Lausanne (24 July 1923), recognised its annexation to England. Cyprus, which on June 4, 1878, was ceded by the Turks to England in exchange for promised military aid to Turkey.

Eleftherios Venizelos lost the elections of November 1, 1920, left Greece and went into self-exile in Paris. Following the referendum on November 20, 1920, with a percentage of 99 per cent, King Constantine I [(1858-1923) (king 1913-1917 and 1920-1922)] was restored to the throne and arrived in Athens on December 6, 1920. As a direct result of the defeat of Eleftherios Venizelos in the elections of the 1st November 1920 and the return of King Constantine I to the throne in November 1920 there was a cooling off in the relations of the allies with Greece, since the Anti-Venizelists and King Constantine I followed a Germanophile policy in the First World War (1914-1918).

The return of Constantine I to the throne, as well as the rapprochement of the Kemalists with the Bolsheviks and the signing of friendship pacts with financial and military aid that alarmed the Allies of the Entente, now gave the Allies, starting with the French and the Italians, of economic and geostrategic interests in the former territories of the Ottoman Empire, to come to an understanding with Kemal and to revise the Treaty of Sèvres at the expense of their ally Greece, which, for them, paid a heavy toll of blood with the great losses it suffered in the First World War.

At the same time, our allies froze credits to Greece, causing huge financial difficulties that were necessary for our country and the Asia Minor campaign.

All this, such as, among other things, the poor economic situation of the families and political controversies, brought our country to a dead end, diplomatically and militarily.

Subsequently, the new government that emerged from the elections of November 1, 1920, although they had promised demobilisation and an end to the war, continued the Asia Minor campaign, now led by King Constantine I and other officials, to enforce the terms of the Treaty of Sevres militarily. The campaign of the Greek army, with an advance towards Ankara in 1921, did not start well, with a repulse by the Turks in January 1921. After this failure, the political and military leadership found itself in a dilemma – to advance or defend. In the end, the advance was preferred, despite the objections of Eleftherios Venizelos, which led to the collapse of the Greek army in the area of Smyrna. A collapse which Venizelos had feared.

In March 1921, despite the successes with the capture of Kutahya – Eski Sehir – and other areas, the main goal, which was the entrapment of the Kemalist forces and their crushing defeat, was not achieved, so the dilemma to advance or defend returned. It was decided to advance on Ankara on August 1, 1921.

In the Sangari River, the Greek army was held back by the fierce resistance of the Turks led by Mustafa Kemal, the so-called Ataturk (Father of the Turks) and on August 29, 1921, the commander-in-chief Anastasios Papoulas [(1857-1935) ( leader of the Greek forces in Asia Minor until 1922 )], ordered the retreat to the line Eski Sehir – Afyon Karahisar.

The battle on the Sangarios River that lasted from 10 to 29 August 1921, marked the end of the advance of the Greek army which suffered significant losses (4000 dead – 19,000 wounded and 376 missing).

The last Greek military success was the repulsion of the Turkish counterattack at Afyon Karahisar in September 1921.

The retreat to the Sangari River meant for Greece the end of hopes that they would impose a military solution on Kemal. Militarily, Greece could not hope for anything at the time, but only diplomatically with diplomatic efforts that also ended in a stalemate, even for the withdrawal of the Greek army from Asia Minor. Meetings with the “big powers” who put their best interests first had no effect.

On August 13, 1922, Kemal Ataturk’s counterattack on Afyon Karahisar took place, with the assistance of the Bolsheviks, France and Italy. Italy, who was a thorn in the side of Greek interests and a key opponent of Greek territorial expansion.

The Greek front broke and from that moment began the retreat of the Greek army, with the dramatic events afterwards, for the unfortunate Greek population in Turkey, as well as the Armenians, but also for the Greek Army there, which then after the great casualties with dead wounded and captured, found itself in Mytilene, Chios and Thrace. The first army corps, with 5000 men and the head Trikoupis, surrendered.

The Greek army left 23,000 dead and 18,000 missing soldiers in Turkey. Also left were thousands of Greeks in Asia Minor at the mercy of the Kemalist army – the Chetes – and the local Muslim population.

On the morning of August 27, 1922, the Turks entered Smyrna and the surrounding area which led to the atrocities that followed under the gaze of the Allied ships that were present. On August 29, 1922, Kemal entered Greek Smyrna and on the same day, the Metropolitan Chrysostomos (1868-1922) – (Metropolitan of Smyrna 1910-1922) was martyred by the Turkish mob.

In Mytilene, the army declared a “Revolution” against the government of Athens led by colonels Nikolaos Plastiras [(1883-1953) (twice Prime Minister of Greece)] and Stylianos Gonatas [(1876-1966)(president of the government 1922-1924)], which overthrew the government of Nikolaos Triantafyllos, which had succeeded Petros Protopapadakis after the collapse of the front at Afyon Karahisari and the Asia Minor catastrophe.

The ‘Revolution’ called for the dissolution of the Parliament, the formation of an Allied friendly Government, the strengthening of the Thrace front and forced King Constantine I [(1868-1923) (King 1913-1917 and 1920-1922)] to leave Greece, who died in Palermo, Italy, and brought to trial the six anti-Venizelists responsible for the disaster, who on November 15, 1922, were sentenced to death and executed on the same day:

- Dimitrios Gounaris (1866-1922) – (Prime Minister 1915 and 1921)

- Petros Protopapadakis (1859-1922) – (Prime Minister 1922)

- Georgios Baltatzis (1868-1922) – (Minister of Foreign Affairs 1908-1909 and 1922)

- Nikolaos Stratos (1872-1922) – (Prime Minister 3 May 1922 – 9 May 1922)

- Nikolaos Theotokis (1878-1922) -( Minister of Military Affairs 9 May-28 August 1922)

- Georgios Chantzanestis (1863-1922 ) – (Lieutenant General, Army of Asia Minor from May 1922 (who succeeded Anastasios Papoulis ) until August 24, 1922).

An execution that, from a moral and legal point of view, was corrupt. Eleftherios Venizelos then assured Panagiotis Tsaldaris (March 5, 1868 – May 17, 1936) leader of the People’s Party after the execution of Demetriou Gounaris that he did not consider them guilty.

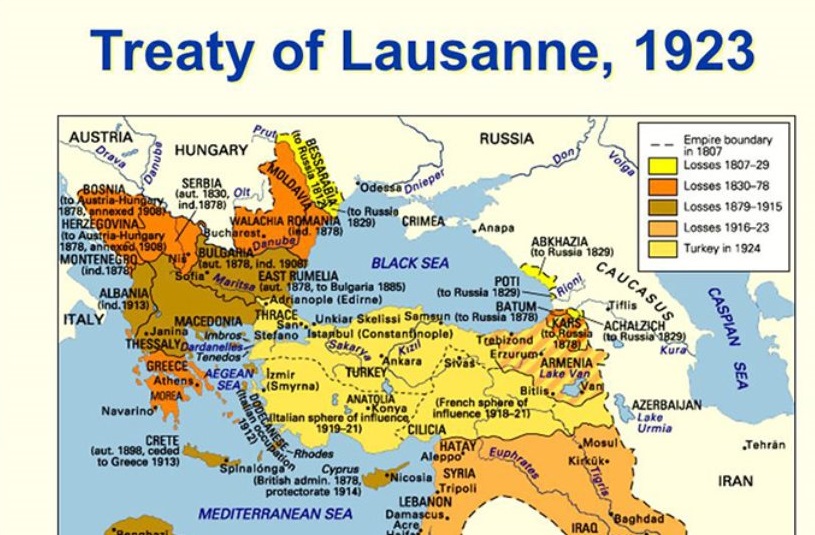

Treaty of Lausanne – 24 July 1923

Eleftherios Venizelos (as previously mentioned) left Greece after his defeat in the elections of November 1, 1920, and went to Paris with grave misgivings for the future. Although far removed from active politics, he warned as early as April 1921 of the disaster he saw coming, and he undertook to salvage what was possible and resorted to lead the negotiations in Lausanne.

The conference in Lausanne began its work on 7/20 November 1922. For Eleftherios Venizelos, the two big issues he was going to face were the border with Turkey in Thrace and the ownership of the Eastern Aegean islands.

A referendum in Western Thrace (with a large Turkish-born population) was not accepted while the demilitarised zones along the Evros River were imposed, which were a test for the demilitarisation of the Straits in the Hellespont.

Italy refused to discuss the status of the Dodecanese but, Chios, Samos, Ikaria and other islands of the Eastern Aegean were definitively given to Greece, as well as that, the islands of the Eastern Aegean, except for Tenedos and Imbros (which was wrong), were recognised as Greek territory.

The insistence of the Turks on the concession of the Greek fleet and on the payment of compensation for the damage caused to Turkey by the Greek army was not accepted.

On January 30, 1923, the convention between Greece and Turkey was signed in Lausanne, Switzerland, imposing the compulsory exchange of populations between the two countries, an exchange that took place involuntarily and based mainly on religion, a proposal that was accepted by the British Minister Lord Corzon in Lausanne on December 1, 1922.

(Eleftherios Venizelos had already proposed at the Peace Congress in Paris in 1919, an exchange on a voluntary rather than a compulsory basis).

The status of the Straits in the Hellespont, Kurdistan, Armenian Asia Minor, the oil-bearing region of Iraq, the Ottoman debt and other issues, were the subject of negotiations with the Great Powers.

The Lausanne Convention would be followed by the signing of the peace treaty of the same name on July 24, 1923, which settled the outstanding issues in the relations between Turkey and the Allies.

The signing of the Treaty of Lausanne in Switzerland put an end to the Asia Minor catastrophe and the Greco-Turkish War (1920-1922).

Under the terms of this Treaty, Greece gave to Turkey Eastern Thrace, the Vilayet of Smyrna, the islands of Tenedos and Imbros, while Turkey renounced all claims to Cyprus and the Dodecanese.

Finally, the exchange of populations between the two countries was agreed.

Despite the reactions and the contrary opinion of Theodoros Pangalos [(1878-1952) (1924-1926 dictator) and Ioannis Metaxas [(1872-1942 ) ( who ruled dictatorially from 1936-1942 )], the settlement of the Treaty of Lausanne, considering the difficulties Greece faced in 1923, was the best possible outcome with what the country achieved (such as the establishment of the borders of Greek status in the islands of the Eastern Aegean) keeping the Patriarchate in Constantinople and preventing Bulgaria from having access to the Aegean Sea.

The Treaty of Lausanne which Venizelos signed without hiding his deep melancholy should be added to his achievements. The treaty effectively abolished the Treaty of Sèvres (signed on 28 July/10 August 1920). He signed it for the good of the Nation after the Asia Minor catastrophe and the diplomatic isolation of Greece, but also to avoid another devastating war with Turkey.

While, with the reorganisation of the army, achieved by the ‘Revolution’ in 1922 in Mytilene, it achieved peace, which allowed the Nation to end the war period (1920-1922) and devote itself to the task of internal reconstruction.

The disaster of 1922 was the most important event in modern Greek history from the creation of the modern state in 1830. This event ended a period of successive expansions of Greece’s boundaries and seals the completion of irredentism for greater Greece. The country turned to internal reconstruction and development.

The treaty of Lausanne brought an end to the 3000-year Greek presence in Asia Minor.

The events of 1922 are an open wound with debates about who is to blame for the disaster, who is to blame for the last chance to create Greater Greece.

Asia Minor and the Pontus are an integral part of our collective memory and identity. However, the centuries-old civilisation of the Greeks of Asia Minor has left an indelible mark on the World Political heritage, a mark that cannot erase any genocide and any uprooting.

The discussions about what happened then do not cease – they burn us, as do the reports every now and then with boasts of the leadership of Erdogan’s Turkey.

The Greek political and military leadership overestimated the country’s capabilities, something that the Great Powers knew at the time. The Greeks underestimated the Kemalist forces whose moral was high and were also better equipped, with Turkey strengthened diplomatically and militarily and supported by the Bolsheviks, France and Italy. And that is why the defeated and militarily neutralised Turks, allies of the German Axis, achieved what they achieved, against Greece, the ally of the victors of this First World War.

The advance towards Ankara – towards the great depth of Turkey of the Greek army was a grave mistake.

The Greek political and military leadership ignored the occasional initiatives, mainly by Britain and France, to mediate an end to the war and sign a peace at the expense of Greece.

And to know that no one, then, as now, as any of us who believes that there is a Nation on earth that wants – that prefers to undertake all the sacrifices required for the liberation of another Nation. Ion Dragoumis (1878-1920) said “Freedom is conquered is not given away by others.”