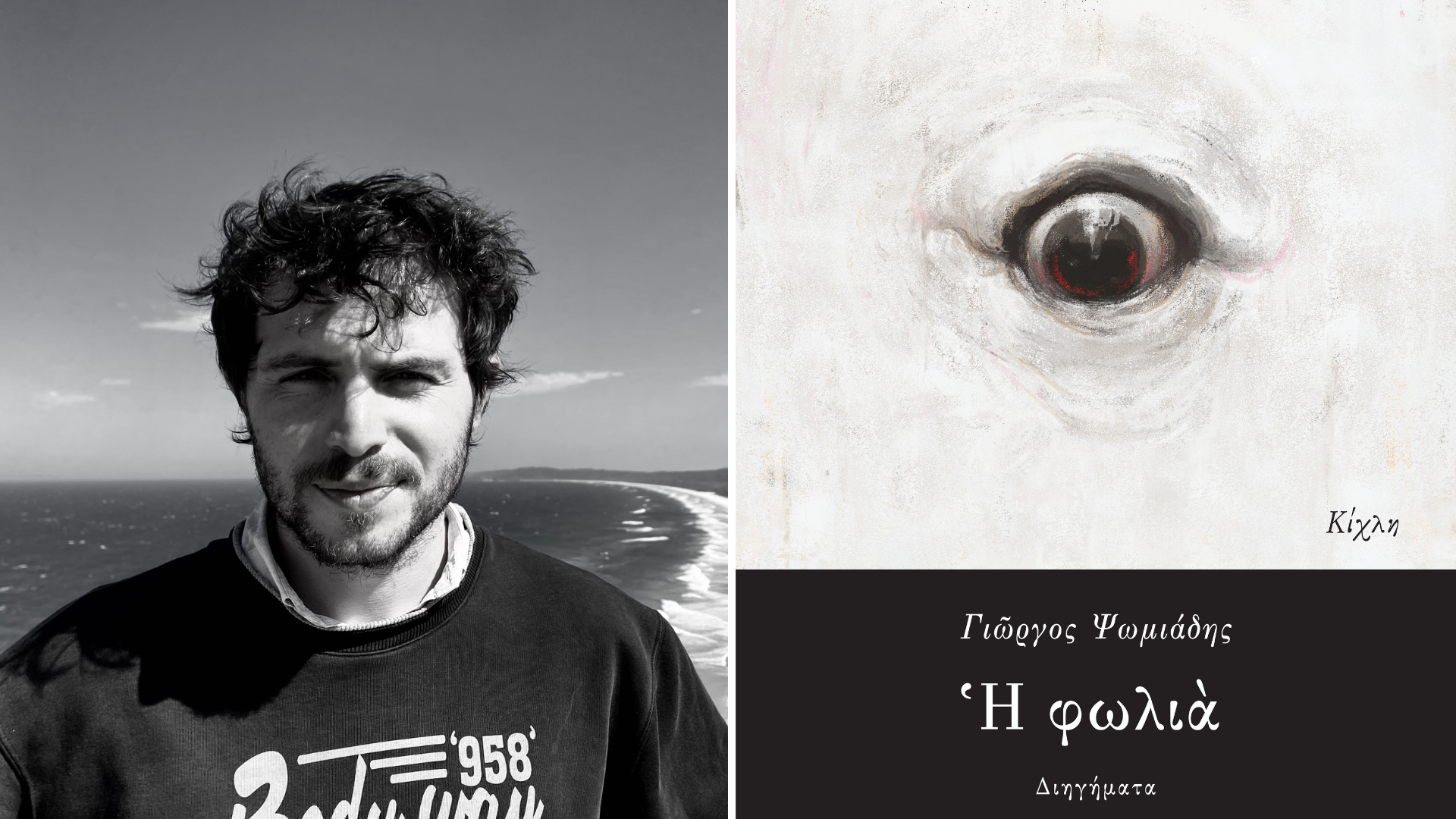

In his debut book, The Nest, Giorgos Psomiadis sketches six characters living on the edge of a personal or collective dystopia – a world that is already present, harsh and often inhospitable.

Through short yet tightly woven stories, Psomiades explores the loneliness of metropolitan life, workplace exhaustion and the alienation brought about by technological dominance, constructing a dark, almost cinematic landscape.

And yet, within this psychological wasteland, his characters persist in searching for something elemental and deeply human: warmth, a sense of family, a refuge. Their own nest.

In his interview with The Greek Herald, Psomiadis – who previously worked as a journalist for the publication during his time in Australia – reflects on the cities that shaped his writing, the influence of diaspora and displacement, and the balance between dystopia and hope that runs through his first book.

Your book «Η φωλιά» (The Nest) presents six characters trapped in various forms of personal or collective dystopia. To what extent did your own experiences living and working in major cities – both in Greece and during your year in Australia – shape the atmosphere of these stories?

Images and experiences I’ve encountered over the years living in those cities are each, in their own way, playing a role in the stories, sometimes clear and sometimes more complex.

Athens appears directly in some of the stories as the location where they take place; the unique character of certain neighbourhoods felt like an ideal backdrop for my protagonists and their inside worlds.

Other stories were written during my time in Melbourne. Being far from home opened up a whole new world for me – one where I wrote daily, wandered through neighbourhoods that often felt like film sets, and allowed what I was witnessing to blend with my past experiences.

Your time as a journalist for The Greek Herald placed you within the Greek diaspora community in Australia. Did that encounter with displacement, belonging and identity influence the way your characters search for a “φωλιά” (nest), a place of emotional refuge?

The Greek presence in Australia is remarkably strong, and observing how the community has shaped its life there showed me how people can create a home away from home.

As a journalist, I witnessed firsthand the love Greek Australians have for their home country and the way they preserve and share values. I would say that the whole “down under” experience at that time of my life provided an environment that benefited the book in a broader sense, creating a distance from my past.

Reporting on diaspora life was a valuable journalistic, real-world experience – not part of the fictional world of the stories, but still a very interesting one.

«Η φωλιά» explores loneliness, technological alienation and the psychological weight of modern life. As a young writer and journalist, what compelled you to turn these anxieties into fiction, and why now?

Some of these stories reflect challenges that we face in our times. We inhabit a reality where lived experience often comes second. It’s a world where we often search for friendship and love through screens, where respect in working environments is not guaranteed and affording the rent for an apartment in a big city is a proper challenge.

Fiction felt for me like the right space to explore some of these anxieties and use them in different ways in the stories of the characters, sometimes also deploying fantasy.

Many of your protagonists cling to small pockets of hope-human connection, memory or imagination. How important was it for you to balance the dystopian tone of the stories with this insistence on resilience and possibility?

The coexistence of dystopia and hope feels natural to me. Darkness often brings fundamental human instincts to the surface. For me, dystopia can become fertile ground for imagination, for dreams, and for unexpected ways out.

Your prose is often cinematic and atmospheric. How did your journalistic background – working with real people, real pressures and real stories – shape your approach to crafting fictional worlds?

I wouldn’t say my experience in journalism shaped the way I crafted these stories. Of course, the two practices require different ways of working, and they should, because reporting on the experiences of real people requires respect for the values and responsibilities of the journalistic profession.

Writing fiction draws from a different place inside me; it blends different influences and emotions. Still, journalism has helped me encounter a wide range of personalities, learn their stories, explore their ways of thinking, and broaden my perspective.

This is your first book. What did writing «Η φωλιά» teach you about yourself?

I learned that publishing a book requires patience and determination – and that you will benefit if you give yourself the space to let inspiration grow into a story. Through working on the book, I learned how to handle the whole creative process, and took lessons that for sure I can use in the future.

You can buy a copy of Georgios Psomiades’ new book here.