Two hundred and four years have passed since 25 March 1821- the official date of the Greek Revolution. This was when Greeks at last co-ordinated, fought in the Peloponnese. Here they gained the first major milestone in their independence from the Ottomans who invaded Hellenism’s Byzantine’s capital Constantinople in 1453.

So much history, so many memories can be rather baffling to a Greek Australian like myself who was born and bred in Australia; a ‘younger’ nation. But this measuring and narrating of ‘official’ history leaves out much: A primarily politically enacted and defined history, often overlooking the fact that common people become pawns.

We are at last recognising politically motivated biases in history, acknowledging for example that Australia means Aboriginal Australia as well. And, here in Greece (where I have been residing for almost 30 years), overdue recognition is being given to the underestimated contributions by Asia Minor Greeks to the Greek Revolution of 1821, culminating in the survival of Hellenism.

Perhaps I myself am suffering from bias in delving into this complex topic, as my grandmother was an Asia Minor Greek. I was fortunate enough to meet her when I was a fresh-faced Aussie arriving in Greece aged 16 in 1984. My surprise at hearing her converse in a strange tongue with another elderly Greek lady hadn’t yet manifested into intrigue to make me want to ask why these two were speaking in Turkish.

“She came to Greece from there (now Turkey) when it was ours, and she was only 13 and came with her elder brother as the others were lost there, when the Turks kicked us out in 1922,” was the narrative I recall getting from a cousin.

I wish I had looked more into her history, my history, Greece’s history, before she died.

I questioned my mother, her daughter, many years later, but she herself didn’t have much to say, nor know much about her mother’s origins.

“I think she was from Constantinople. Your poor grandmother had many children – I was the 7th and last. She was always busy washing, cooking…”, was her response.

I did learn from my mother that my grandmother had brought customs with her from Asia Minor, such as spiced aromatic food, and giving her babies “a little bit of milk from the poppy plant to help us sleep.” Very exotic stuff!

Perhaps my grandmother couldn’t or didn’t want to put into words the trauma of her fleeing from her Asia Minor homeland, from a homeland of millions of Greeks for over 3,000 years until Ottoman domination. I wonder in what forms inter-generational trauma carried through in many subtle but powerful ways to the second and third generation of Asia Minor Greeks like myself.

I live close to a suburb here in Athens called Nea Filadelfia, 6 kilometres north of the city centre. It is an Asia Minor refugee area founded just after 1922. This was the year of the ‘Megali Katastrofi’ – the ‘Great Disaster’ – an event originating from the ‘Megali Idea’ – ‘The Great Idea’ – for Greeks to be freed from Ottoman rule. The plan included a desire to restore Greece to its 1453 pre-Ottoman occupation borders, but went wrong due to awry foreign and Greek political decisions.

Though the Greek Revolution of 1821 succeeded in mainland Greece, things in Asia Minor were a lot tougher. Attempting many times to revolt within the approximately 400 years of Ottoman invasion, the Asia Minor Greeks were swiftly and barbarically put down by the Ottomans who outnumbered them.

Finally, culminating dramatically in 1922, the largest expulsion of Asia Minor Greeks happened with over 1.5 million arriving as refugees in Modern Greece. Nea Filadelfia is one of several suburbs in Athens – and other parts of Greece – named after the Asia Minor refugees’ origins. (Original Filadelfia was a town in Asia Minor established in 189BC.)

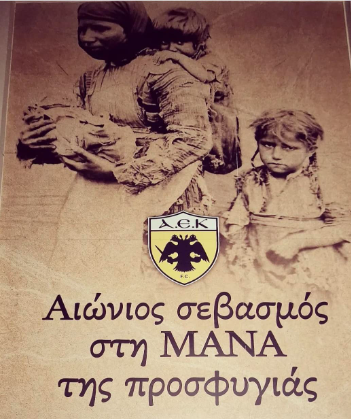

Nea Filadelfia is also the home of one of Greece’s most popular soccer teams – AEK, a Greek acronym for Athletic Association of Constantinople. Their fans are very passionate and still consider Asia Minor their former homeland with its stadium’s architecture resembling Aghia Sophia Church from Constantinople, adorned both inside and outside with historical reminders of Asia Minor heritage, as well as housing a museum.

I meet up here with 3rd generation Nea Filadelfia resident, also historian and researcher at the Centre of Asia Minor Studies, Dr Dimitris Kamouzis. We talk about AEK amongst many things, and he explains that Asia Minor people tend to be more politicised than the mainland Greeks because when they arrived in mainland Greece, they had to fight to be accepted, they had to work harder to prove themselves as Greeks.

The Asia Minor Greeks who fled slaughter (around 1 million Asia Minor Greeks left behind didn’t) and arrived in mainland Greece, with only the clothes on their backs, faced the wrath of many Greeks here. Called ‘tourkospori’ – turk seeds – and ostracised for their poverty, as they had to leave hurriedly to save their lives even though many led much more cosmopolitan lives than the mainland Greeks, their integration was made difficult by the above-mentioned defensive and ignorant attitudes.

Dr Kamouzis considers an important, definitive event of the Asia Minor Greeks’ involvement in the Greek Revolution of 1821 – the Turk’s slaying Patriarch Gregory V who to the Ottomans served as a scapegoat representative of the Greeks’ struggle for independence. This is indicative of the Ottomans’ many torturous reprisals towards the Greeks of Asia Minor as they bravely planned, enacted and struggled for their independence.

We know that Alexandros Ypsilantis from Constantinople was one of the first to attempt revolt before 25th March 1821. Ypsilantis formed the ‘Philiki Etairia’ – the ‘Society of Friends’ – a movement that spread the seeds and deeds of Greek independence to areas such as Constantinople, Cappadocia, Ionia (mainly in Smyrna), Cydonia-Aivali and Pontus. There was also Adamantios Korais (1748-1833), an intellectual from Smyrni who energetically, and internationally, advocated for a Greek Renaissance, greatly influencing Philhellenism. And these were only two men in a plethora of Asia Minor Greeks contributing to the Revolution in many ways.

A special army was formed by Asia Minor Greeks – the Column or Phalanx of the Ionians (1826 -1828) – which gave its combative presence to the Revolution. There were also the many Asia Minor Greeks who immediately joined the military corps of chieftains, such as Nikitaras, Makrygiannis, Gouras, and Kolokotronis in mainland Greece.

Much money and weaponry were donated by Asia Minor Greeks for the Revolution, including a ship full of ammunition to the Peloponnese enabling the Revolution to first succeed in Kalamata in March of 1821, and then spread to the rest of Greece.

Asia Minor women showed their patriotism and love for freedom in many ways too. The actual banner held up by Bishop Germanos signalling the beginning of the Revolution was made by a woman from Asia Minor, and donated to Greece in the 17th century.

This brings to mind what Dr Kamouzis tells me about the old, now abandoned factories in Nea Filadelfia where textiles were made and where many of the 1922 Asia Minor refugees worked, as they excelled in artistic textile design.

“The area with its carpet and cloth, including silk factories, was known as ‘Little Birmingham,’ due to its industry,” Dr Kamouzis says.

But the Asia Minor Greeks also excelled in many, many fields such as administration and trade, stemming from their geography and ensuing Byzantium culture dating back to antiquity.

Another signifier of their cultured, cosmopolitan Asia Minor ways, Dr Kamouzis refers to, is parks. Yes, parks.

“Nea Filadelfia has a big ‘Alsos’ park, and note the other Asia Minor suburbs such as Neas Smyrni also have these beautiful, green leisure spaces,” he explains.

We also discuss that much of the tasteful architecture in Nea Filadelfia, unique to Greece, is based on the refugees Asia Minor abodes.

“These houses were built just after 1922 in consultation with the Refugee Settlement Commission,” Dr Kamouzis says, testifying to their administrative prowess.

My mum, not wanting to return to her homeland Greece but content to remain in Australia, often refers to Greece as ‘Psorokostaina.’

The real name of ‘Psorokostaina’ was Panoria Chatzikosta, the wife of wealthy merchant Kostas Aivaliotis, and the mother of four children. She lost them all in the years of the Greek Revolution when the Turks massacred the area of Aivali from where she hailed. Ending up in Psara then Nafplio, she became a poor beggar. Nasty, taunting children there nicknamed her ‘Psarokostaina,’ which evolved to ‘Psorokostaina.’

During the siege of Messolonghi (1826), a fundraiser took place, whereby she was the first to donate her only possession, a golden wedding ring. This humble act moved the other Greeks, resulting in the table then being loaded with offerings.

She was eventually hired as a volunteer laundress at an orphanage in Aegina where she died much-loved, where the orphans there washed her with their tears and accompanied her to her grave. The term is a metaphor for the economic situation of Greece. It’s also symbolic of the fate of Greece after the woes of our history (foreign powers’ manipulations included), but is nonetheless also indicative of our love for freedom, independence and sacrifice for our country and our people.