*By Fotini Manikakis (originally published in Signals magazine)

Our family’s story of migration to Australia shares a common thread with the story of so many people across the globe who, propelled by seismic historical events, embarked on a journey to an elsewhere, hoping for a better life.

The world our parents left behind was rural, pre-industrial village life on the remote Greek islands of Limnos & Agios Efstratios, in the North-East Aegean Sea.

Greece, like most of Europe, felt the ravages of WWII and the Nazi occupation deeply. Afterwards, while most of Europe was rebuilding, it faced additional struggles – a further five years of civil war sparked by the recalibration of geo-political spheres of influence and the interference by foreign powers in its domestic affairs. The devastation that ensued forced an entire generation to flee poverty, political instability and persecution to seek economic opportunities elsewhere and plant seeds of regeneration and hope.

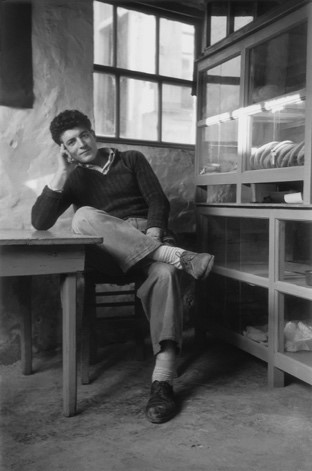

In our family, this responsibility fell to our father, George Manikakis, who at 22, was asked to make this sacrifice for the greater good of his family.

The difficult post-war years of intense poverty and political unrest were pivotal in shaping George’s world-view. He witnessed great inequality and human rights abuses first hand. The island where he was raised was one of the many remote islands used to banish and detain thousands of political prisoners who were involved in the pro-democracy movement, suspected or charged for being leftists or communists – a threat to the interim provisional government that had been installed by the British in lieu of free-elections.

George saw some of Greece’s best and brightest citizens: politicians, lawyers, teachers, scientists, academics, workers, resistance fighters, unionists, writers, musicians and artists, imprisoned, tortured and murdered for defending and speaking up for what they believed.

This chance exposure to the ocean of knowledge and ideas that descended on his small island shores was life changing. It fuelled his commitment to social justice and human rights movements throughout his life, including his 65 years in Australia. Here he contributed tirelessly to the labour movement, the anti-war and anti nuclear movements, the fight to end apartheid, the struggles for Australian Indigenous rights and to campaigns opposing the brutal establishment of military juntas around the globe.

On New Year’s Eve in 1956, after completing a full day’s work in the family bakery fulfilling hundreds of village orders for Vasilopita (Traditional New Year Cake), George hung his apron for the last time, farewelled his beloved family and with great sadness turned his back on his village and beautiful island home for what he feared would be the last time. He then embarked on a 19,000km journey by ship to Australia to find work to support his extended family and to feed, clothe and educate his five younger siblings.

His sense of duty to family was such that he did not question or argue, but found the resolve to make the voyage with purpose. After arriving in Australia on the “Skalkoum”, he picked grapes in Mildura, Victoria, then found work at a dairy farm near Parkes, New South Wales, before securing jobs in a myriad of inner-city factories in Adelaide then Sydney, where he often worked two jobs to make ends meet. Eventually, he became a waterside worker, employed on the wharves in Sydney until his retirement.

Our mother, Helen Manikakis, came to Australia as a proxy-bride, to marry a man she had not met. The union was arranged by their parents; a common practice among families whose young women, following the mass exodus of men, faced shrinking opportunities at home. Marriage and starting a family were cultural and social rites of passage, so arranged marriages were seen as the most viable option. The men who had moved to Australia were keen to marry a girl from home, and so matchmakers on both sides of the globe worked hard to secure successful unions.

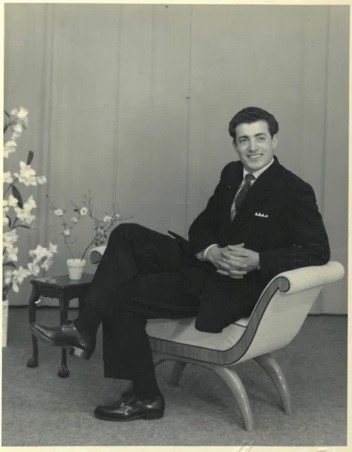

Mum remembers that she was working in the fields not far from her house when she was told to smooth her hair, straighten her clothes and head back home because prospective in-laws were arriving. The story goes that when our father’s parents saw our mother, they instinctively knew she was a match for him. They showed her his photo (he really did look like a Hollywood movie star), sparking a twinkle in her eye. A year of correspondence between them evolved into a formal engagement celebrated with family and friends – with George in absentia. In May 1959, Helen boarded the “Flaminia” to Australia to meet and marry him.

Helen speaks of the fear and immense pain of leaving family, but also a sense of excitement and curiosity about what lay ahead. She promised herself that if he wasn’t what he seemed, she would turn around and come straight back home. They married as planned, however, and both worked very hard to support relatives in Greece, buy their own home and start a family. With time their union became a love match.

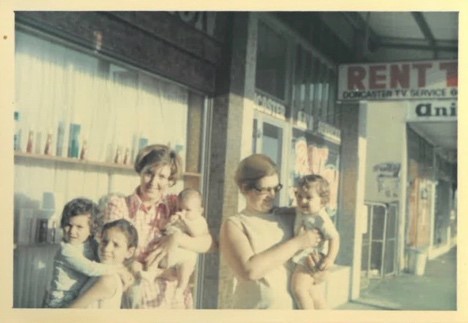

George and Helen laid the foundations for other family members to make the journey – George’s sisters Elizabeth and Fani, then Helen’s brothers Nikolas and Pantelis, and later her parents George and Fotini. With family settled in Sydney and their letters filled with stories about life in Australia, the journey for those who followed was not as precarious. Family helped other family make the transition and supported them to establish new lives.

For instance, when Elizabeth arrived as a newly trained hairdresser, George and Helen found a shop for her to start her business, and they all moved in together above the premises. They renovated the shop to create Elizabeth’s Hair Salon in the Sydney suburb of Kensington. In the 1960s and early 70s, women queued for hours to be styled by Elizabeth, who had arrived with a selection of the latest European hairdos including the conical beehive and the bouffant, but expanded her repertoire in no time to master local favourites such as the blue rinse perm. Fani had trained as a beauty therapist joining the business a few years later, before transferring her clients to Helen when she decided to pursue tertiary studies.

Elizabeth’s Hair Salon was run with the spirit of community typical of a Greek village (with kids in tow) and the essence of Greek hospitality or filoxenia; good coffee flowed freely as did generous helpings of homemade sweets. A visit to the salon was more akin to an intercultural party, where relationships were forged and great friendships made. Customers loved the sense of care, belonging and connectedness they encountered at the salon, and for Elizabeth and Helen, as working mothers of young children, it provided a bridge to a new world. Customers helped them navigate their new life in Australia: providing advice on schooling, sporting activities and academic pursuits; explaining the meaning of expressions like ‘bring a plate’ or customs like the Easter hat parade; extending invitations to the annual Melbourne Cup luncheon; and giving hints on how to enter yiayia’s (grandmother’s) treasured embroideries into the Royal Easter Show.

John Ziros who became Elizabeth’s husband, arrived in Australia in May 1960 on board the Patris. They met at the Greek Atlas Club while performing in one of the many plays that were staged there. John worked as a taxi driver for many years before studying and qualifying to become a medical interpreter for the NSW Department of Health.

Together they all helped their sister Fani to realise her dream to study science at Sydney University and become the first family member to secure a tertiary education.

In Australia, this story is not a singular one. Our family was one of thousands who, in their shared plights and experiences, quests and objectives, found solace, camaraderie, strength and purpose – the village ethos transplanted to the suburbs of Sydney with a spirit of generosity and possibility. Migrants helped one another, forging new connections that cemented and set the foundations for a broad, active and vibrant community in Australia.

George, Helen, John, Elizabeth and Fani, along with many others worked tirelessly for their community. They raised funds to build churches and schools; helped to create advocacy and welfare groups that provided information, translation services and language classes; and organised cultural and social events such as dances, musical performances, theatre productions, picnics, feast days, national days and festivals. They were a few of the many who sowed the seeds for a two-way cultural exchange that helped to transform Australia, and whose legacy is enmeshed in the fabric of our nation’s story.

Honour our Greek immigrants on Australia’s National Monument to Migration at the Australian National Maritime Museum. Register by 30 June 2022 to be part of the next ceremony in October. To register please visit this website or call (02) 9298 3777.