By Dean Kalimniou

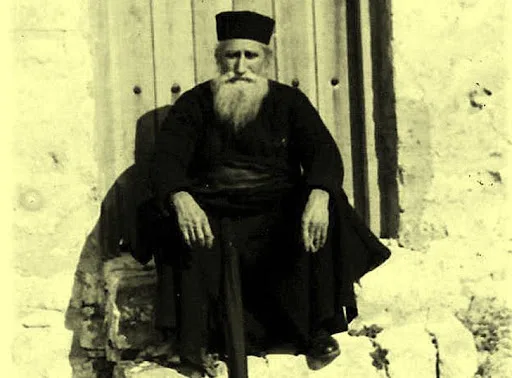

In July 2025, the Holy and Sacred Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate formally added the name of Saint Dimitrios Gagastathis to the calendar of saints.

The canonisation of this revered married priest and confessor, whose holiness was long attested by popular piety, represents a continuation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s venerable commitment to discerning and proclaiming the presence of sanctity within the life of the Church. It reflects a tradition of spiritual discernment anchored in patristic wisdom, ascetic vigilance, and pastoral sensitivity.

Notably, Saint Dimitrios Gagastathis was the father of nine daughters, a detail which underscores the significance of his sanctification as a step toward affirming the sanctity that can emerge through the lay and familial life.

And yet, a broader pattern in the canonisations of the past decade invites theological and ecclesiological reflection. While the Orthodox Church possesses a deeply rooted understanding of the sanctity accessible to all the baptised, the official recognition of saints has recently centred predominantly upon those who are monastics or ordained clergy. This emphasis, while coherent within the context of Orthodox spirituality and tradition, risks underrepresenting the sanctifying potential inherent in the lay state.

By contrast, the Russian Orthodox Church has, over the past century, canonised not only hierarchs and new martyrs but also laypersons whose lives bore the unmistakable imprint of divine grace.

One moving example is the canonisation of the companions of the last Imperial Family of Russia, including not only the Tsar and his family but also their faithful attendants: Dr Eugene Botkin, the royal physician; Ivan Kharitonov, the cook; Anna Demidova, the maid; and Alexei Trupp, the footman. These were not monastics, nor were they ordained. They were ordinary Christians who, in the final hour, bore witness with courage and loyalty, sanctifying their deaths through solidarity and fidelity.

Similarly, the Roman Catholic Church, while doctrinally distinct, has elevated the sanctity of lay life to a visible theological principle. It has canonised individuals such as Saint Gianna Beretta Molla, a physician and mother who sacrificed her life for her unborn child; Saint José Sánchez del Río, a fourteen-year-old martyr of the Cristero War; Saint Isidore the Farmer, whose piety and simplicity became a model of rural sanctity; and Louis and Zélie Martin, the parents of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux, whose married life was a profound testimony of holiness. These figures exemplify how sanctity may unfold not in monastic seclusion but amidst the routines and burdens of modern life.

It must be emphasised that Orthodox theology is unequivocal in its affirmation of the sanctity of the lay state. From the earliest centuries, the Church has recognised soldiers like Saint George, physicians like Saint Panteleimon, and rulers like Saint Constantine as vessels of holiness. The theology of theosis, so central to the Orthodox understanding of salvation, envisions all the faithful as participants in divine grace.

As Saint Gregory Palamas taught, the divine energies are not the exclusive inheritance of the ascetic few, but are offered to all who struggle toward likeness with God, however unassuming their vocation.

Sainthood, in this light, must be understood not merely as exceptional heroism, but as the fruit of cooperation with divine grace within the concrete and often hidden circumstances of everyday life. The late Father John Meyendorff, building on the patristic legacy, spoke of sainthood as the manifestation of the transfigured person within the ecclesial body. This vision affirms that holiness can arise in any context, urban or rural, professional or domestic, visible or obscured. The sanctification of the layperson is not a peripheral anomaly; it is intrinsic to the catholicity and incarnational logic of the Church.

The sociological implications of this theological truth are profound. As Father John Chryssavgis has incisively asked, should we not question why so few women or laypersons are advanced for canonisation, and why the aura of sanctity is so often confined to the male, monastic, and clerical domains? He challenges us to expand our ‘radar for sanctity,’ asking why we privilege solitaries over spouses, monastics over seculars, miracle workers over those whose lives radiate empathy, decency, and practical solidarity with the suffering. He goes further, questioning whether our reverence for saints might sometimes obscure rather than aid our spiritual growth. Drawing on Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor, Father Chryssavgis warns against a spiritual economy fixated on miracle, mystery, and authority, those same temptations Christ refused in the desert.

Might our yearning for saints endowed with supernatural powers reflect a deeper human fragility, a desire for emotional certainty and external validation? When we venerate miraculous charisma more eagerly than sacrificial compassion, we risk domesticating holiness into something predictable and palatable. Lay saints, those who embrace suffering with faith, who bear injustice without bitterness, who love without recognition, embody these moments. They are not exceptions but prophetic signs of the Church’s potential to speak to the deepest human longings.

Peter Berger, too, reminds us that for religion to remain existentially plausible, it must articulate the sacred within the structures of ordinary life. Berger’s vision of “plausibility structures” in religious belief reveals how saints of the everyday restore credibility to the sacred by inhabiting the world with reverent transparency. Their holiness is not imposed upon the world, but drawn from within it, revealing the presence of God in the mundane and the marginal.

Canonisation, therefore, is not merely a retrospective recognition of sanctity. It is a forward-looking proclamation of what kind of life is capable of bearing divine light. In recognising lay saints, the Church does not relativise the monastic vocation, but extends the monastic spirit into the hearth, the marketplace, the hospital ward, and the schoolroom. It bears witness to the radical unity of Christian life across all vocations. Spiritual vigilance, or nepsis, becomes not only a monastic discipline but a universal mode of attentiveness—possible amidst the cries of infants, the fatigue of labour, the noise of history.

The canonisation of Saint Dimitrios Gagastathis, in this sense, is emblematic of a sanctity that does not retreat from the world but transforms it from within. His life as a father of many daughters, a parish priest rooted in the soil of his people, a spiritual father open to all, reveals that the ascetical life can be lived in the very texture of the familial and the pastoral. Grace does not require isolation. It transfigures relationality, reconfigures fatigue as prayer, and renders every gesture capable of becoming Eucharist.

As Orthodox theologian Christos Yannaras has insightfully argued, the Church is not merely an institution but a mode of existence—a way of being that unfolds in love, freedom, and truth. In this ontology, the saint is not defined by role or status, but by participation. The sanctity of the layperson is not an exception. It is the sign of a Church alive in every limb, responsive to every whisper of the Spirit.

From a theological perspective, the renewed attention to lay sanctity would deepen the Orthodox vision of conciliarity and catholicity. It would reaffirm that holiness is diffused throughout the body of Christ, as Saint Paul wrote: “Now there are varieties of gifts, but the same Spirit” (1 Corinthians 12:4). The dogmatic teachings of the Church affirm this variety of grace; canonisation makes it visible.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate, as the primatial see of global Orthodoxy, carries the weight and dignity of a witness that shapes the entire Orthodox world. Its discernment of sanctity is therefore not only pastoral but ecclesiological. A broader embrace of lay sanctity would not dilute this witness. Rather, it would broaden its resonance, revealing that the Spirit blows where it wills, and often in unexpected quarters.

In a world disillusioned by clericalism and craving authenticity, the proclamation of lay saints would offer a theologically robust and spiritually compelling model of divine-human cooperation. It would testify to a Church that remains in the world without becoming of it, a Church that does not idealise the cloister but sanctifies the courtyard, the classroom, and the kitchen.

Perhaps the next saint to be recognised will be a mother who taught her children to pray through silence, or a neighbour who gave bread to the stranger, or a worker who resisted injustice with gentleness and perseverance. These lives, luminous and hidden, remain among the Church’s most precious gifts.

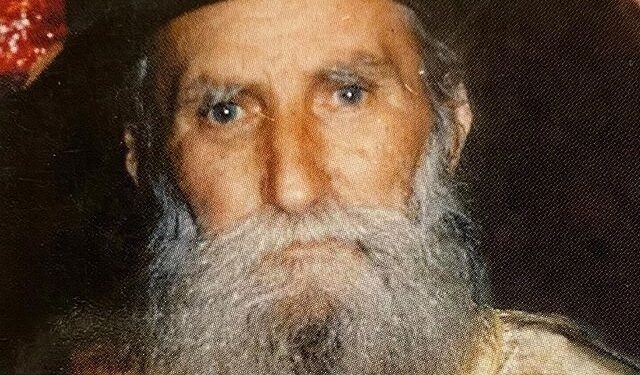

Among such examples is Saint Dimitrios Lekkas, a lay Orthodox Christian known for his unwavering humility, deep prayer life, and tireless service to those in need. His memory endures as a quiet yet profound inspiration, reminding us that sanctity does not always wear a cassock or dwell within monastic walls. Lives such as his are not only spiritually edifying but also theologically vital, offering the faithful tangible models of holiness lived amidst the ordinary rhythms of the world. The time has come to bring them to light, with reverence, theological precision, and ecclesial love.