By Mary Sinanidis

The Hellenic Returned and Services League (RSL) sub-branch in South Melbourne is described as a “hub” by the Greek Australian ex-servicepeople who frequent it. Connected by a deep reverence for history, they share stories forged on battlefields from Rhodesia and Korea to Afghanistan and Vietnam when they meet each Saturday for a coffee, a game of cards and some social connections.

Dennis (Dionysis) Patisteas, a former Oasis coffee merchant, served as an officer from 1961 to 1963. He tells The Greek Herald: “We talk about everything, share viewpoints, and these days we talk a lot about how we will organise ourselves in the ANZAC Day parade. We are the only Greek Australian organisation represented on ANZAC Day and are extremely proud of this.”

On ANZAC Day, Mr Patisteas says he is moved by the deep connection he feels for his two countries.

“Our mother homeland is Greece which we yearn for, but we feel a deep love for Australia because it is the country that welcomed us and gave us so many opportunities,” he says.

Hellenic RSL President, Manolis (Manny) Karvelas, points to the ANZAC Day march protocol with the Australian army, Commonwealth armies, followed by allies of Australia in different wars. The Turkish RSL also marches though technically the Diggers fought with Turks in Gallipoli.

“Turks were enemies in World War One, but not in Korea,” he says. “They were Australian allies at some point and that’s what matters.”

“By rights we can march with our own troops and with the Hellenic RSL.”

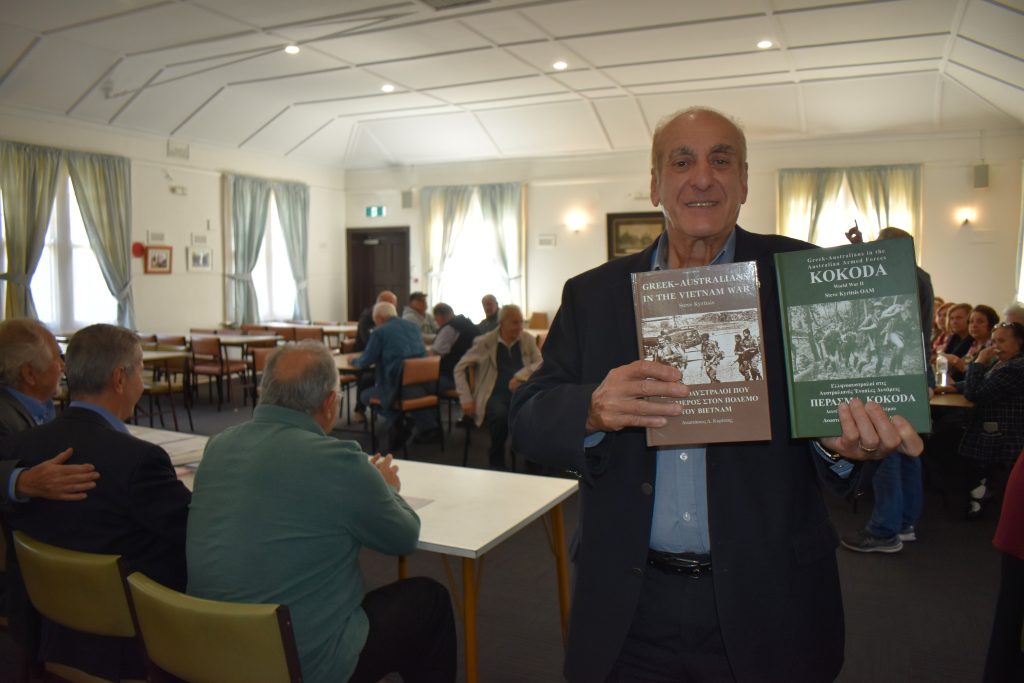

Former Hellenic RSL president, Steve Kyritsis, will do just that when he marches with Vietnam veterans before running back to jump in with his Greek Australian cohort.

Sydney-born engineer Arthur (Athanasios) Baoustanos, who served in the Greek army from 1987 to 1989, says that he feels “proud of the appreciation Australians have for the Greeks that helped them during WW1 and WW2.”

“Serving in the Greek army is a great experience, where I learnt discipline, made connections, and enjoyed a great culinary experience in Thessaloniki where most of my service was. I’m encouraging my son to do this even though he doesn’t have plans to live there,” he says.

At the Hellenic RSL clubhouse, those who served in the Greek army mingle with Australian veterans. Though some served in times of peace and others in war, they were all willing to put their lives on the line for kin and country.

The ones who went to war

Dimitris Varnas, a carpenter who served in the Greek military in 1964, was ready for war with Turkey when his troop went to Evros on the Greek-Turkish border.

“Our thoughts were on how we would beat the Turks, that’s all,” he says. “I had no fear. I was 20.”

There’s a reason why young men go to war, says Peter Stathopoulos – a former sub-inspector of the British South African Police in Rhodesia from 1967 to 1969.

“You are more likely to follow orders when you are young. At 30, they question your directions, but at 22 they just do what they are told,” he says. “When you see people marching, they aren’t just doing this to keep fit. When they listen to an order they are being trained to hear and follow directions.”

Mr Stathopoulos understands the importance of this from his experience in the Civil War in Rhodesia.

“I was born in Greece, brought up in Australia, and went to Rhodesia in an exchange in the police force in 1966,” he says.

“I was in charge of 40 men, dealing with guerrilla warfare with hit-and-run tactics and ambushes, but I can tell you this: I wasn’t as worried about the bullets as much as I was about the snakes – the deadliest. You step on a minefield and you die or get medication, but when you get bitten by a snake it is a slow and torturous death even if a doctor is right next to you. Snakes are worse than bullets.”

Some talk about war teaching them discipline, but Mr Stathopoulos remembers learning “how to live off the land, how to survive.”

He came back to Australia to continue working in law enforcement.

“I don’t have PTSD,” he says. “For my time in Rhodesia, I get $5,000 Zimbabwe a month pension which is $32.20 and costs me $30 to access.”

He laughs at the irony.

Ioannis Michanetzis, who served in the Greek Navy for 21 years from 1987 to 2008, listens to Mr Stathopoulos carefully. Having lived in Rhodesia for the first 10 years of his life, he feels a familiarity with some of the war tactics though he served for Greece.

“I knew my career had reached its end in 2008, when I was posted as a governor of a warship. Were I to stay on, I would then move onto a desk job and did not want the politics which comes with that,” he says.

“I served in Yugoslavia where there was direct combat and was part of numerous anti-terrorist missions. I miss the good times, the adventure. It was the largest part of my life, and the training helps you easily surpass your fears. Twenty-one years of crises, battles and experiences. I was away from home a lot; the longest was for a year, but my wife was a commander, so she understood.”

In Australia since 2012, he is the general manager of an aged care facility, in an industry which fought its own battle during COVID-19.

He signed up to the Hellenic RSL because he feels a strong bond with all the men who go there.

“We all have something in common. We served our country, and that unites us,” Mr Michanetzis adds.

Importance of the RSL

The Hellenic RSL president looks at me and asks, “What do you think? There are so many stories in this room.”

Stories are important to document and honour, but on a more practical level, being a member of the RSL connects veterans to services, and offers care and support.

There are four Hellenic RSL sub-branches in Australia, including Melbourne, Canberra, Sydney and Brisbane.

Kostantinos Katsambanis, a mountain commando from Greece, says a Greek organisation was established just after the end of World War II to support Greek Australian servicepeople who had served in the Greek or Australian armed services.

“We had a small organisation at first and it took us two years to be approved as an RSL group in the late 1970s,” he says.

A big step for the Hellenic RSL but an even greater achievement for the Australian RSL which had been described in the late 1970s as an organisation considered conservative, “Anglophilic” and “monarchist.”

Times have changed and the RSL has benefitted greatly from embracing diversity and welcoming even more heroes to its fold. It’s a happy ending for those who survived. An opportunity for more people to dust off their war medals and march to Melbourne’s Shrine.