By Mary Sinanidis.

Elpida Hatziandreou’s life is a narrative of Modern Greek history.

What began as a refugee tale from Asia Minor ended as a story of Australian migration with a few twists amid major periods in world history. From the Spanish Flu pandemic, Elpida lived to see COVID-19, survived cancer, and ended up dying of old age in 2021.

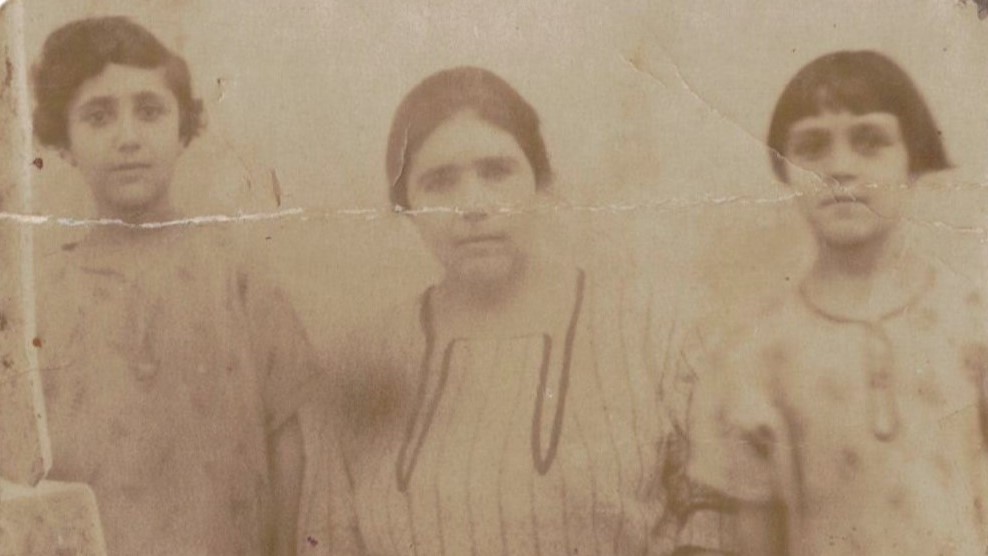

The second child of Nicholas Tsakiris and Olga Rigopoulos was born on Christmas Eve 1919 while rosy-cheeked children were singing kalanta door-to-door in the seaside town of Vourla. At the time, her father was held hostage in a Turkish prison for not enlisting in the army and was lost before Elpida could walk.

A time of hope

“Sure, it was tough, but it was also a time of hope,” her daughter Cathy Alexopoulos told The Greek Herald. “And that’s why they called her Elpida, which translates to hope. Her older sister, Despina, was named after her father’s mother, but they broke with tradition and called my mother Hope.”

In nearby Smyrna, a landing force of 13,000 soldiers and auxiliary personnel, and 13 transport ships escorted by three British and four Greek Destroyers were at work. They had been “received with great emotion” by the Greek population according to accounts at the time, while thousands of Turkish residents gathered on hilltops lighting fires and beating drums in protest.

Greek Colonel Nikolaos Zafeiriou, who led the expedition, said: “Wherever we may go, we must know that we are going to liberate our brethren under alien rule.”

In Vourla, known for its excellent tobacco, quality fish and A-grade grapes, life went on as usual.

“My mother’s family owned vineyards. They produced spirits like tsipouro and famed golden Smyrna sultanas,” Ms Alexopoulos said, adding they were also capable merchants.

“A strand of the family later moved to Mildura. They brought with them from Smyrna, the ‘cold dip’ process of curing sultana grapes which revolutionised the dried fruits industry in Australia because, until then, local farmers had dipped grapes in a hot caustic soda solution which created a dark brown hardened mediocre sultana rather than the golden sultanas produced in Smyrna.

“They also joined the Chaffey Brothers during Victoria’s wine boom, and they did well.”

Vourliots were known for their prowess in Roman wrestling, but also for the poetry of Nobel laureate Giorgos Seferis and bravery of Georgios Afthonidis, one of the most prominent members of the Filiki Eteria created to free Greeks from Ottoman rule.

“My mother didn’t remember much from her birthplace,” Ms Alexopoulos said. “The family had to leave everything behind in 1922 during the Catastrophe. As fires burnt, the spirits they had in storage blew up. Everything was lost.”

Ms Alexopoulos speaks of her family’s deep faith.

“My uncle Christos Rigopoulos, the youngest son of the family, fought the Turks, and took with him this icon of Saint Catherine, the patron saint of his mother. He said that this icon is what protected him, and he later became a priest and moved to Patras (northern Peloponnese) and married a local woman there.”

Ms Alexopoulos shows me the family icon, her namesake, with scrawling on the back which neither of us can make out. Words lost in history.

With Christos in Patras, the women were left to fend for themselves when making the crossing from Vourla to Greece.

“My grandmother Olga, widowed with two children, and her younger sister Androniki, also widowed, with a small child, left Turkey. Unfortunately, her son Vasilakis died of gastroenteritis on the long and difficult journey to Greece,” Ms Alexopoulos said.

“They did not go to Smyrna and so, thankfully, avoided the fire but they paid someone to transport them to Greece, taking with them all they could, a bit of gold hidden in their clothes and a Bible.”

From Patras to Lyon

Once in Patras, the situation was bleak. “Racism was rampant. They were called Tourkosporoi (Turkish seeds) and doors were slammed in their faces when they asked for work or some help,” Ms Alexopoulos said.

The women were called ‘pastrikies’ (meaning ‘clean’ but alluding to ‘whores’) because they washed their clothes more than the local women did.

“They sold their jewellery, their liras and somehow survived, but they didn’t stay long.”

Androniki, who spoke fluent French, encouraged Olga to leave for France, and so began a new journey which took them to Lyon.

It was in Lyon where Olga married her second husband, Petros Menengos, who worked at Citroen. The family lived in Venissieux at the Chalet de bois (wooden houses) which had been given to them by the car company to stay, and the new marriage was further solidified with the birth of Georgia, a half-sister for the older girls.

“These were my mother’s first and fondest memories,” Ms Alexopoulos said.

“She remembered the snow, the chestnuts, riding her bike. They lived simply and had a garden which grandma Olga would tend to.”

For free-spirited Elpida, life was a dream. “She wanted to cycle and run, but Despina, her older sister was calmer and spent her time reading. For my mother, France was a place where she could be herself. She went to school and had positive memories. She belonged.

“The bad thing is that they returned to Greece.”

From Lyon to Aigion

Compensation offered to Asia Minor refugees drew Olga to Aigion, and she reunited with her brother the priest and Androniki, who had left France years earlier and had settled in Aigion with a well-to-do shopkeeper Antonis Mihalos who did well from the sale of Papastratos cigarettes.

For Elpida, the small town of Aigion was ‘suffocating’ following the freedom of France. “Her uncle, the priest, made her feel shame,” Ms Alexopoulos said. “There were closed minded attitudes and Elpida was told she could not ride her bike and was constantly told not to wear things and do things. She felt repressed.”

Her fluent French made her a sought-after tutor. World War II found her in Corinth, where she taught the children of an affluent family.

The death of her sister Despina from tuberculosis, aged only 21, drew Elpida back to Aigion in 1939.

“For grandma Olga, losing her elegant, beautiful, cultured Despina was the biggest blow of all,” Ms Alexopoulos said, who remembers her grandmother Olga, as a woman who seldom smiled. She worked hard creating delicate embroideries which she sold or bartered when times were tough.

Back in Aigion, Elpida found her mother in the depths of despair and even the curtains were painted black.

“My mother became the man of the family during the war. She’d teach and try to bring an income. How did she survive? With courage,” Ms Alexopoulos said.

Sought after by a number of suitors, the family insisted on a groom from Asia Minor. “That is how my mother married my father, Nikos Hatziandreou, in 1946,” Ms Alexopoulos said. “He had been eight when he left Asia Minor and fought in Crete during WW2, where he met many ANZACs there at the time.”

The birth of Cathy Alexopoulos

“I was born in Komotini because my father worked with the United Nations Relief Fund and was stationed there at the time,” Ms Alexopoulos said. “It was a temporary job, and the family went to Athens in 1948 with my brother born in Nea Ionia (a northern suburb of Athens).”

Her younger sister, Georgia, married her second cousin, Ulysses (Odysseas) Xeros from Mildura and paved the way for Elpida’s family to follow.

Cathy remembers her first years in Australia.

“I missed Athens,” she said. “We lived in Nea Filadelfia and we got up to mischief and had a great time. Our teacher at school was Kyria Kalliopi, who was also from Asia Minor and good friends with my mother. My last school excursion was to the Acropolis and was heartbreaking as I knew I would leave and couldn’t fathom what it would be like, ‘What do they do in Australia? How do they speak?’

“I went to Kent Street Primary School, in Richmond, and was a tall 9-year-old but they put me in a class with 6-year-olds because I did not know the language. All I knew was that my name was Catherine and how to say ‘thank you’ and ‘please’. Something I remember was trying to play with the other kids and they would say ‘get out’, ‘get out’, but to me it sounded like ‘keraia’ (antenna). So I ended up hanging out with my brother during lunch.”

Cathy insisted she attend school with Year 4 students when the family moved to St Alban’s, and things began to improve.

Her mother, Elpida, eventually got a job as a cleaner at the Saving’s bank. She started the same week grandmother Olga died of breast cancer on 17 January, 1961, and did not take the day off work because she was new and eager to make a good impression. On her way to work, she heard fire trucks pass by. Little did she know, they were for her St Alban’s house reduced to ashes due to an electrical fault.

Once again, everything was lost, and yet again, Elpida would rebuild. And they made a life for themselves at St Alban’s, where Ms Alexopoulos’ father was a founding member of the St Alban’s Greek Community and had forged strong bonds.

Life continued in Australia with joys, but also loss and grief. Elpida was diagnosed with cancer, twice, surviving both times despite tumours the size of golf balls.

Elpida’s remarkable story, filled with twists, turns and resilience may have been what inspired her daughter to study history and French.

I ask Ms Alexopoulos how her family’s history has affected her. “I think what it does is, it enrichens you, it makes you more perceptive and open to what is happening in the world. More inclusive and tolerant,” she said.

We discuss family trauma. “No, not trauma. What I feel is proudness. I’m not sure if the word is ‘blessed’, but I definitely feel that there is an essence about the spirit of these people, and that is what I want to carry.”