The Larcos family could never have anticipated the upheaval that awaited them when they made the decision to relocate from Australia to Cyprus in 1970. Four short years later, their lives would be turned upside down.

A father’s dream for his family would be shattered but what gripped him the most was guilt for moving his family to Cyprus.

The Greek Herald sat down with three generations of the Larcos family — Savvas, his sons George and Christopher, and grandson Tim (Christopher’s son) — to talk about the Turkish invasion of Cyprus in 1974 and how the family re-bounded after losing everything.

Moving to Cyprus in 1970

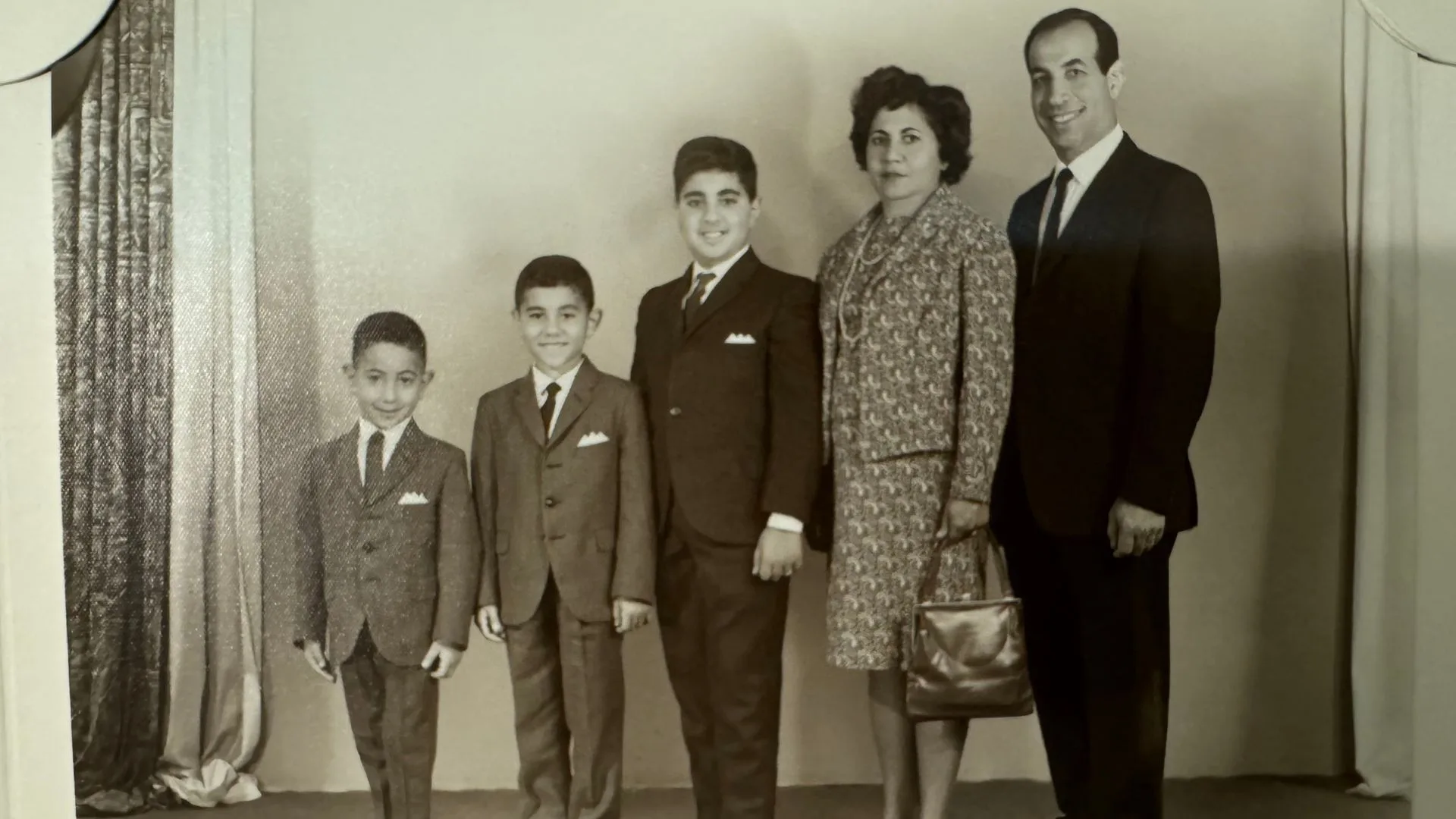

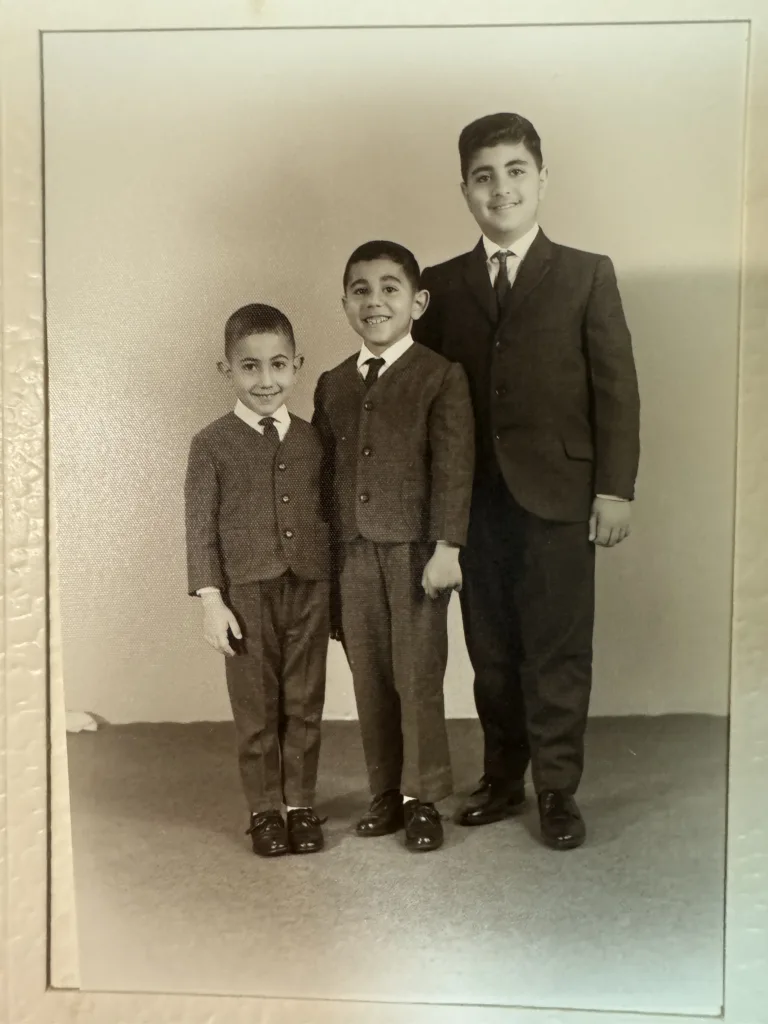

Selling the family home in Sydney, Australia, Savvas and late wife Aliki would take sons Christopher, George and younger brother back to their homeland of Cyprus in 1970.

“Most of the migrants, they wanted to work five or six years in Australia and go back to where they came from. But, when you leave your homeland, there was a reason to leave,” Savvas told The Greek Herald.

Much of his family still resided in Cyprus at the time, part of the reason he wanted to go back.

As the family packed for their return, Savvas’ wife opposed the decision, wanting to stay in Australia as most of her family was there. Her brothers also warned it was potentially not a good move, aware of political troubles abroad and forecasting that the country’s future was uncertain.

But as a property developer in Australia, Savvas did quite well, making capital and taking it to Cyprus to start a company with his brother and his friend, juggling work at the airport as a chef and waiter to support the family.

Savvas and his business partners had property in Famagusta and Kyrenia.

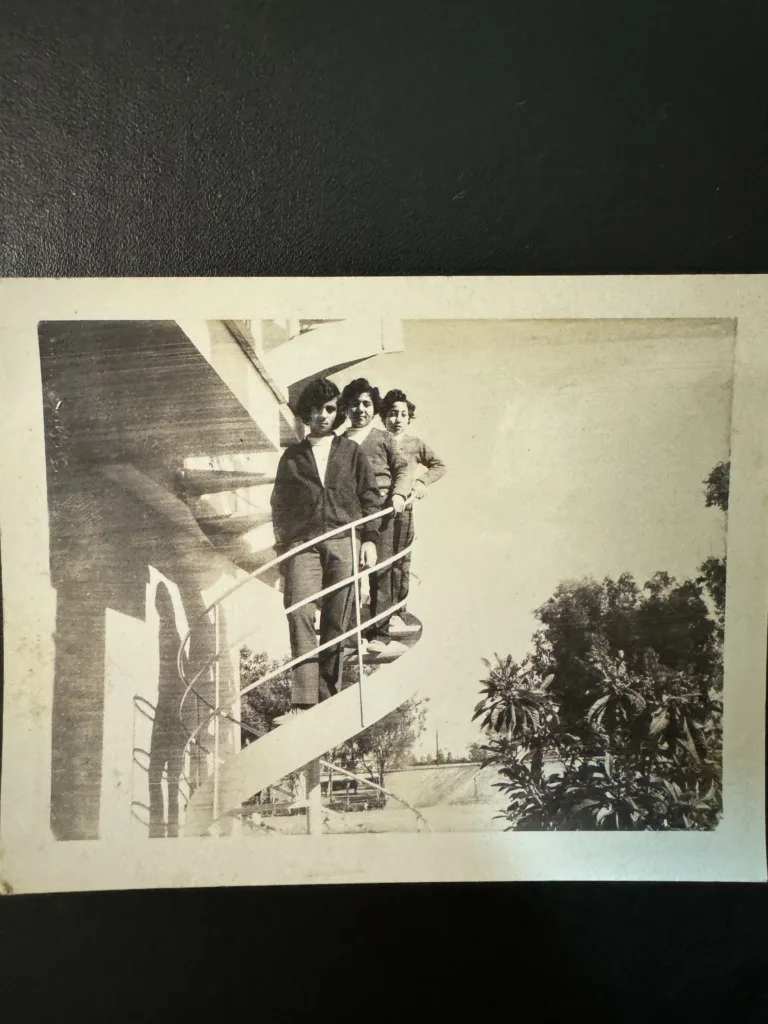

George said life before the war was positive. The brothers were receiving a good education and setting up for their futures.

“My memories pre-war were positive—we had holidays, we would go to the beach regularly, we would visit relatives in Kyrenia and Kontara, take trips to Limassol—a standard happy childhood,” he said.

“The move to Cyprus didn’t cause any emotional issues. It was a wonderful life, and things were being set up well.”

Christopher gives a different perspective of moving to Cyprus.

“At first, I didn’t like the idea of being uprooted from life in Australia to this place on the other side of the planet which I didn’t know,” Christopher said, before adding that after a couple of years at school and making friends, life was good.

“I was home by then.”

By the time 1974 came, the brothers felt at home in Cyprus and could see a positive future ahead, with plans for university abroad. The Larcos family began to settle into their new life.

The day of the invasion

On the verge of the family business booming — their entire livelihood would be uprooted overnight. Savvas had found a buyer for one of his properties in Kyrenia near the water. Selling the property would have set up the family financially.

The very next day, Cyprus was invaded by Turkish troops.

“The morning of the invasion was quite traumatic,” Christopher said, reflecting on the day as a then-17-year-old.

“My habit at the time was to wake up at 6am daily and listen to the BBC World Service. The lead story that morning was about the invasion. I thought, ‘that’s interesting. I don’t see anything’.

“I looked out the window to the north and saw Turkish parachutes coming out of the sky.”

George added, “It was scary. People were using real weapons, they were shooting at you, there were bombs, our home is damaged, there was also a lot of uncertainty… Suddenly, your childhood was being stolen, evaporating right in front of our eyes. You grow up very quickly. You go from a 14-year-old who’s interested in match box cars to realising there is a real world out there. Our situation changed dramatically.”

When Savvas returned from his shift at the airport, the boys saw the fear on his face and could sense the seriousness of the situation as Turkish jets flew above them, and paratroopers landed.

Huddling downstairs in the family home with their neighbours, explosions carried on through the night keeping the family awake.

Escaping to the mountains for a couple of weeks to hold out, the family wanted to see what the chances were of going back. Sleeping out in the fields, underneath a car, near a tent — everything was up in the air.

“We stayed with other families, and we thought it was going to be temporary, maybe a few days, maybe the Turkish people would change their mind, and everything would go back to normal. But that was a full-on hope,” George said.

It quickly became clear things were not going back to the way they were.

“We didn’t have our bedrooms anymore,” George explained.

“There was a lot of unhappiness and tears. For the first time in my life, I saw that my parents were vulnerable people themselves.”

Christopher added, “As a kid you realise there is a big threatening world out there. You see your parents emotionally devastated. Economically, it’s a catastrophe, they’ve lost everything, and everything is uncertain. That was the reality for us.”

Losing his employment and business, and forced out of the family home, Savvas also lost his property investments, which are still occupied by Turkish military today.

“He lost his economic livelihood overnight—it evaporated,” Christopher said. “We had sold our family home in Australia as we planned to stay in Cyprus.”

Savvas’ grandson Tim weighed in on the experience and said, “I think there’s a sense of guilt about going to Cyprus from Australia. He had made the choice to take the family back, and four years later all of this [happened]…I think he wears that a bit even though it has nothing to do with him.”

Rebuilding the family legacy

Returning to Australia months after the invasion, the family started over from scratch.

While living in a small apartment, Savvas worked three different jobs —a breakfast chef by morning, lunch chef and waiter at night. In five years, the family had enough money to put a deposit on a house—the house he now lives in as a 96-year-old.

“I felt responsible for what happened. I said to myself, ‘now you are going to be strong and bring your family back together, like a captain of the ship’,” Savvas said.

“I had to show them that you can go back and find yourself again. I never gave up.”

George said he built an admiration for his folks: “They knuckled down and both worked multiple jobs. They really put effort into re-establishing themselves.”

In retrospect

Looking back now on the events of 1974, George said they made him see his parents “in a different light.”

“There were a few silver linings—it helped me gain a mature outlook on life. I went from being a 14-year-old kid to having a much more mature thought process,” George explained.

“I had enormous admiration for my parents, and I didn’t want to disappoint them, so this made me more resilient, having experienced being shot at, I was determined to make something of my life and please them in doing well.”

Christopher said he has “a different experience.”

“I don’t know if I recovered from the trauma. I think I’m over it now, but I don’t know what the steps were that got me here. I had the opposite reaction to George,” Christopher said.

“I got angry and ended up blaming my parents for it. You know, I thought, ‘this is a mess, it’s all your fault and my life is a mess.’ I carried that anger with me when we came back to Australia.

“I was unfocused, I was traumatised by the Cyprus experience, there was no one to talk to, to help talk it through and resolve it, so my life started to go off the rails. It was lucky I got into the architecture degree, as that helped a bit… I’m lucky to have made it out of my 20s.”

Resilience and the impacts of generational trauma

Savvas’ grandson Tim expressed that he “mirrored” his father Christopher’s trauma during his upbringing.

“I heard about the recovery process a lot growing up. He talks about getting shot at by troops. For me, hearing those stories amplified those stories in terms of generational impact,” he said.

Nonetheless, Tim said the family’s ability to overcome such diversity has instilled in him a resilient mindset.

“I’ve seen how resilient the family have been—you have doctors, lawyers, a diplomat—there’s a high bar that has been set in terms of the generation before,” Tim explained

“It’s largely because of this man [Savvas]. The choices he made have set entire generations up for success. I know he laments the choice of going back, but we wouldn’t be in this situation today if it weren’t for the choices he made.

“If they stayed in Cyprus, would I be the person I am today? Probably not.”

Today

Witnessing his children grow up, marry and give him grandchildren and great grandchildren, Savvas said, “For me, this happens to lots of people. It’s all part of life; success and failure.”

Savvas walks up to 5 kilometres daily and still drives. He prides himself on his ability to do online banking. His reflective attitude on the invasion—and the impacts—reveal a man determined to protect and keep his family together at all costs.

“After all this catastrophe, I’m almost 97, I’m so proud, you can’t imagine how proud I am, I’ve got three children, well educated, financially independent, I see my grandchildren become good citizens, that feeling, that positive feeling—you can’t take it away from me,” Savvas concluded.