Today marks 50 years since the passage of the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA) – the landmark legislation that made racial discrimination unlawful in Australia and laid the foundation for a more inclusive and equitable nation.

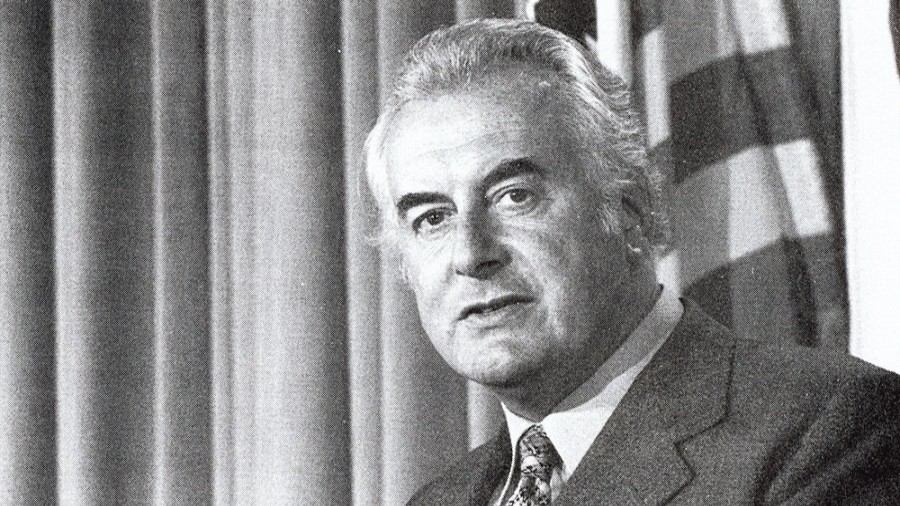

Introduced under the Whitlam Government, the Act transformed Australia’s moral and legal landscape, giving legislative force to the principle that equality must be both protected and lived.

For many, including Greek Australian lawyer Dean Kalymniou, the anniversary is deeply personal. A lifelong admirer of Gough Whitlam, Kalymniou views the Act not only as a cornerstone of modern Australian justice, but as an enduring reflection of Whitlam’s belief that multiculturalism is central to democracy.

Speaking to The Greek Herald, he reflects on his encounters with Whitlam, the influence of Hellenic thought on Whitlam’s vision, and the ongoing challenge of turning legal equality into lived reality.

You have spoken before about your admiration and personal connection to Gough Whitlam. How did that relationship shape your own understanding of justice, equality, and Australia’s multicultural identity?

My association with Gough Whitlam shaped my understanding of justice as a living discipline rather than an abstract ideal. Through his example I learned that equality demands participation, dialogue, and the courage to enlarge the moral boundaries of a nation. Whitlam dared to regard migrant Australians as partners in a shared enterprise, and in that recognition lay a quiet revolution.

For Greek Australians, his leadership was an affirmation of belonging. His government broadened access to education and welfare and created structures that treated cultural identity as an integral part of citizenship. Translation services, community language programs and migrant resource centres expressed a philosophy of inclusion. When the Racial Discrimination Act of 1975 became law, equality was no longer an aspiration but a right.

Whitlam’s bond with Hellenic civilisation deepened this vision. He had studied ancient Greek and retained a lifelong affection for its clarity and balance. When speaking at Greek community events, he often used phrases in our language and spoke with ease about our poets and philosophers. Those gestures affirmed that our heritage had entered the national story, that we were participants, not guests. Through him I came to see that justice depends on mutual recognition, and that a nation’s greatness is measured by the dignity it extends to all its citizens, not just a privileged few.

Can you share how your friendship or encounters with Gough Whitlam began? What impression did he leave on you personally and professionally?

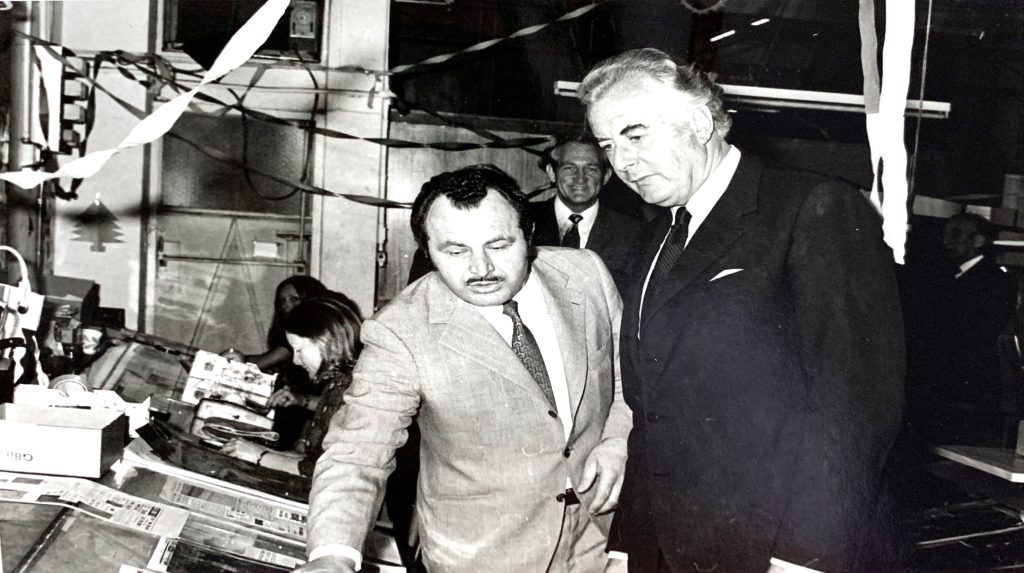

I first met Gough Whitlam when I was 18, decades after his time as Prime Minister, at a Greek community function in Melbourne. Although he no longer held office, the admiration surrounding him remained palpable. People crowded around, eager to greet him, yet when I approached and told him that I considered him a great Australian, he took me aside at me and asked, with characteristic composure, “What do YOU think constitutes a GREAT Australian?”

That exchange began a friendship grounded in conversation and curiosity. What struck me was his attentiveness. Even amid noise and bustle, he listened as if that moment alone mattered. In later meetings he retained the same calm interest, asking questions that provoked deep reflection.

In our exchanges over the years, he taught me that public life is an ethical vocation for all, that policy and law are instruments of moral imagination. Personally, I was moved by his civility and his capacity to draw wisdom from anyone willing to engage in honest thought. His influence endured because it was founded on respect, the rare quality that makes leadership humane.

Is there a particular moment or conversation with Whitlam that has stayed with you — something that encapsulates his character or his vision for an inclusive Australia?

A moment that remains vivid is a conversation about the return of Gurindji land at Daguragu. As he recalled placing a handful of soil into Vincent Lingiari’s hand, his voice carried pride and solemnity. He described it as the reconciliation of law and conscience, a gesture that restored balance to the nation’s history. It was the embodiment of his conviction that justice must be anchored in the earth from which a people draws its life. I remember thinking that in that gesture there was something of the ancient rituals in which land and law were bound together. In that instant, Whitlam restored the moral grammar of a nation.

That account resonated deeply with me. The modern Greek story is one of dispossession and endurance, of lands lost and regained through faith and perseverance. As descendants of those who have known exile, we are instinctively attuned to those who work to heal injustice. In Whitlam’s act toward the Gurindji people, I recognised a truth that transcended politics: that moral restoration is the highest form of leadership.

Gough Whitlam had a long standing affection for Australia’s Greek community, recognising its contribution to multicultural Australia. How did he express that connection, and what did it mean to you personally as a proud Greek Australian?

Whitlam’s relationship with the Greek community was marked by warmth and genuine understanding. He saw Greek Australians as integral to the national story, a people whose experience enriched the moral fabric of the country. Having studied ancient Greek, he spoke of Hellenic culture with knowledge and admiration, and often addressed gatherings in Modern Greek. Such gestures carried quiet power. To hear the nation’s leader speak our language was to feel our identity affirmed.

He also championed the study of Modern Greek at Australian universities, arguing that education should reflect the society it serves. Through his advocacy, Greek language programs gained institutional standing and respect. He believed that the intellectual life of the nation should mirror its diversity, that every citizen’s heritage contributes to the whole. His engagement, however, extended beyond language.

When I once told him about the Pontian Genocide, he listened with characteristic attentiveness, and later wrote to me having undertaken his own research. He told me how profoundly moved he had been to discover that Dr H. V. Evatt, the great Labor statesman and jurist, had played a decisive role in formulating the legal concept of genocide in international law through his work at the United Nations. Whitlam’s curiosity was always ethical in nature. He was drawn to moral questions of memory and justice, to the ways in which history can be redeemed through understanding and acknowledgment.

He also spoke of his visit to the Acropolis and of his conviction that the Parthenon Marbles should one day return to Greece, for he believed that heritage belongs to the conscience of its people. Through gestures such as these, he joined the moral with the cultural, recognising that justice and beauty arise from the same source.

It was evident to me that he recognised in Greek Australians a people who had preserved dignity through hardship and who understood the meaning of democracy because they had inherited its ancient vocabulary. His attentiveness reinforced in me the conviction that Australian identity is a dialogue, and that our voice within it carries equal authority.

Whitlam often spoke about democracy, philosophy and civic duty — values deeply rooted in Hellenic thought. Do you think his admiration for Greek culture influenced his political vision, and how has that shaped your own outlook as a member of the diaspora?

Whitlam’s political imagination drew upon a serious engagement with Greek thought. He saw in classical philosophy a mirror through which a society might examine its conscience. The Athenian experiment inspired his belief that democracy is a discipline of mind, sustained by reasoning citizens rather than passive subjects.

He often reflected that the worth of a state lies in the moral intelligence of its people, a view that echoes the Greek conviction that politics is an extension of ethics. This spirit gave his reform program its depth. His pursuit of educational access, cultural pluralism, and social justice flowed from the belief that a nation prospers when all its people are empowered to contribute. In this, he resembled the philosopher statesmen of the classical age: he wanted to govern through the persuasion of ideas rather than the manipulation of interests.

When we spoke about Greek history, his curiosity was boundless. I once told him of Eumenes’ reforms in Heliopolis, that remarkable Hellenistic experiment in civic equality, and he was fascinated by its attempt to reconcile idealism with administration. Years later, I described to him the revolt of the Zealots in Byzantine Thessaloniki and their vision of a society free from hierarchy. He listened with delight and wonder. Both episodes appealed to his sense of justice and his faith in human perfectibility. He recognised in those distant moments of Greek history the same moral energy that animated his own life, the conviction that governance must mirror ethical order. Accordingly, Whitlam invited us, the descendants of migrants, to see our heritage as contributing to a continuing conversation between justice and statecraft.

This year marks fifty years since the Racial Discrimination Act became law under Gough Whitlam’s government. As both a lawyer and someone with a personal connection to Whitlam, what does this milestone represent to you?

The 50th anniversary of the Racial Discrimination Act invites reflection on how far we have travelled in our pursuit of formal as well as substantive equality. Passed in June 1975 and coming into force that October, the Act gave legislative form to Whitlam’s conviction that equality must be protected by law if it is to flourish in society. It was an act of moral clarity and political courage.

As a lawyer, I regard the Act as one of the most lucid expressions of justice in our statute book. It translated moral principle into enforceable language, providing redress to those whose dignity had been denied. It required the nation to see discrimination as an affront to its conscience. The Act has endured because it was built on conviction rather than expedience. It stands as his testament, a reminder that equality must be renewed through vigilance and the quiet labour of justice.

From a legal perspective, how transformative has the Racial Discrimination Act been in shaping Australia’s human rights landscape? Are there any landmark cases or reforms that, in your view, best demonstrate its enduring importance?

The Racial Discrimination Act reshaped Australian law by giving equality a legal and moral foundation. It affirmed that the protection of human dignity is a duty of the state.

In Koowarta v Bjelke Petersen, the High Court upheld the Act against constitutional challenge, confirming that the Commonwealth could legislate for human rights under the external affairs power. This decision anchored fairness within the constitutional order and made the defence of equality a federal responsibility.

In Gerhardy v Brown, the Court deepened the meaning of equality, recognising that laws designed to assist disadvantaged communities may advance justice rather than compromise it. Later, in Jones v Scully and Toben v Jones, the courts extended the Act to the realm of public speech, condemning anti-Semitic vilification both in print and online. These cases established that the dignity of ethnic minorities is integral to civic peace and that free expression carries with it an ethical duty of respect.

Together, these judgments revealed the quiet strength of the Act. Through them, the law became a custodian of civility, binding the many strands of the nation into a single moral fabric. It endures because it reflects a truth at the heart of Australian life, that dignity shared among many does not divide a nation, it completes it.

Despite half a century of progress, systemic racism still exists in many parts of Australian society. Where do you see the biggest gaps between the Racial Discrimination Act’s intent and the reality people experience today?

Half a century on, the Racial Discrimination Act remains a guide to conscience, yet its vision is fulfilled only through constant effort. The law forbids discrimination, yet inequality still shadows education, employment, housing, and justice. These are the unseen domains where unfairness survives through habit and neglect.

Those most in need of protection often lack the means to claim it. Legal redress can seem remote or daunting, and justice must be made accessible before it can be effective. Equality is achieved when fairness becomes a habit of life, not merely a right of appeal.

We must commit to these laws with renewed resolve. The world around us shows how swiftly societies can fracture and how easily fear can turn neighbour against neighbour. Australia has known such moments, from the Cronulla riots to the recent wave of anti-Semitic violence, yet we have also shown resilience. The instinct for decency still outweighs the impulse to divide. We remain a country capable of strong disagreement conducted with respect.

The Racial Discrimination Act continues to remind us that unity is sustained through civility and that a nation’s worth lies in how it hears its most vulnerable voices. To live by that principle is to keep faith with Whitlam’s vision of a society where freedom and respect walk together.

Gough Whitlam once said, “The real test of any government is not how popular it is, but how it treats those in need.” In that spirit, how can today’s leaders and the legal community uphold and extend the vision that inspired the Racial Discrimination Act fifty years ago? What part can the Greek community play in this?

Whitlam’s words still define the measure of leadership. The test of government is compassion translated into policy, and the test of law is the protection it affords to those who stand at the margins. The Racial Discrimination Act was conceived in that spirit and remains a living covenant between the state and its citizens.

Leaders today must recover the moral courage that animated Whitlam’s reforms. The legal profession must continue to preserve the integrity of justice, ensuring that it remains accessible and relevant to new generations. True equality requires vigilance and the capacity to calm division before it becomes resentment.

Whitlam believed that language was the breath of identity, and through the establishment of multicultural broadcasting he ensured that the many voices of Australia could be heard in their own tongues. In doing so, he gave form to the principle that cultural recognition is inseparable from democratic freedom. We must preserve it.

The Greek community has a distinct part in this continuing work. Our history, both ancient and modern, has taught us the meaning of exile and renewal. As heirs to a civilisation that gave the world the language of democracy and as migrants who once stood at the periphery of Australian life, we understand both privilege and vulnerability. This dual inheritance enables us to foster dialogue and empathy in an age that sorely needs both. Our own journey, from the uncertainty of arrival to full participation, mirrors the nation’s passage from exclusion to recognition.

We honour Whitlam’s legacy when we champion education that celebrates diversity, build bridges across communities, and stand beside those who face exclusion. Our presence here played a large role in constructing Australia’s broader generosity at a time when it could have chosen to embrace insularity instead. It falls to us now to extend that generosity to others. In doing so, we sustain Whitlam’s faith that the greatness of a nation is seen in the breadth of its humanity and in the embrace it extends.