Some people can lay claim to titles such as the ‘world’s oldest person’ or ‘world’s most powerful,’ but not just anyone can call themselves the last living survivor from the Kalavryta Holocaust of December 13, 1943.

That title belongs to 99-year-old Angelos Bouris.

Born in the Greek village of Kerpini in September 1924, Mr Bouris was just 19 years old when German troops conducted a large-scale massacre of the entire male populations of Kalavryta and nearby villages in the Peloponnese region of Achaea.

More than 693 civilians were killed by Germans across twenty-eight towns, villages, monasteries, and settlements. Mr Bouris was one of only four men who managed to escape the atrocities in Kerpini. Their names, along with the names of those killed, can be found at a memorial on Kapi Hill.

So, to mark the 80th anniversary of the Kalavryta Holocaust this year, Mr Bouris shared his powerful story of survival with me for The Greek Herald.

‘I thought he was playing dead’:

The Kalavryta Holocaust started in smaller Greek villages such as Mr Bouris’ hometown of Kerpini on December 8, 1943.

The massacre was in retaliation for the execution of 78 German soldiers by Greek guerilla fighters who were hiding out in the mountainous area surrounding Kalavryta.

Mr Bouris said he was never afraid when he heard German fighters were approaching Kerpini.

“I knew I would escape and they wouldn’t get me,” Mr Bouris told me.

At first, Mr Bouris took refuge in the attic of his house until it was set alight by the Germans, forcing him to flee. He, along with other men from the village, was captured and forced to march in a line towards Kalavryta.

Mr Bouris, his cousin George and friend Ntino, managed to sprint out of the line, racing up a hill behind the local St Barbara’s Church and into the basement of an abandoned house. They were spotted though and Mr Bouris vividly remembers four bullets flying past his head. One bullet hit George, killing him instantly.

“I said to myself, ‘he is playing dead.’ But when I turned his body around, blood and liquid was coming out of his mouth. I knew he was dead then so I closed his eyes,” Mr Bouris said.

‘My whole life has been destroyed’:

Once inside the abandoned basement, Ntino hid himself behind a large wine barrel and Mr Bouris pulled a wooden wheel in front of the barrel to conceal him. The then-19-year-old ended up hiding in a small spot between the barrel and the wall of the basement.

Mr Bouris said he saw two German soldiers walk into the basement but they didn’t see them.

“They searched the area around the barrel. A soldier flashed his torch in one direction but could not see me because I moved away. As he moved back the way he had come, I went back in the direction to where I had just been. I remained behind a part of the barrel he could not see and they didn’t find Ntino either,” Mr Bouris explained.

“I think they decided we had left the basement because they turned to leave, but not before they set part of the place on fire.”

To escape the flames, Mr Bouris and Ntino climbed through an opening in the ceiling of the basement to the ground floor of the house. Jumping out of a window, the pair escaped and made their way back to the village’s main centre, hoping the Germans had left.

“We bumped into an old lady who told me, ‘Your father’s crying and screaming that he’s lost his kids, his house. He’s saying his whole life has been destroyed’,” Mr Bouris said.

In the end, Mr Bouris reunited with his family but his father was right – Kerpini had been destroyed by the Germans, with wives left to bury their dead husbands or children and priests praying over their graves.

“There was nothing left,” Mr Bouris said.

In total, 45 men were killed, machine gunned to death in the field of St Paraskevi. Four who had originally been captured survived, including Mr Bouris and Ntino.

Over the following days, the Germans entered Kalavryta and on December 13, 1943, they slaughtered all men and boys over 14 years old. This was one of the largest massacres of civilians carried out in Western Europe by German troops during World War II.

Later years in Australia:

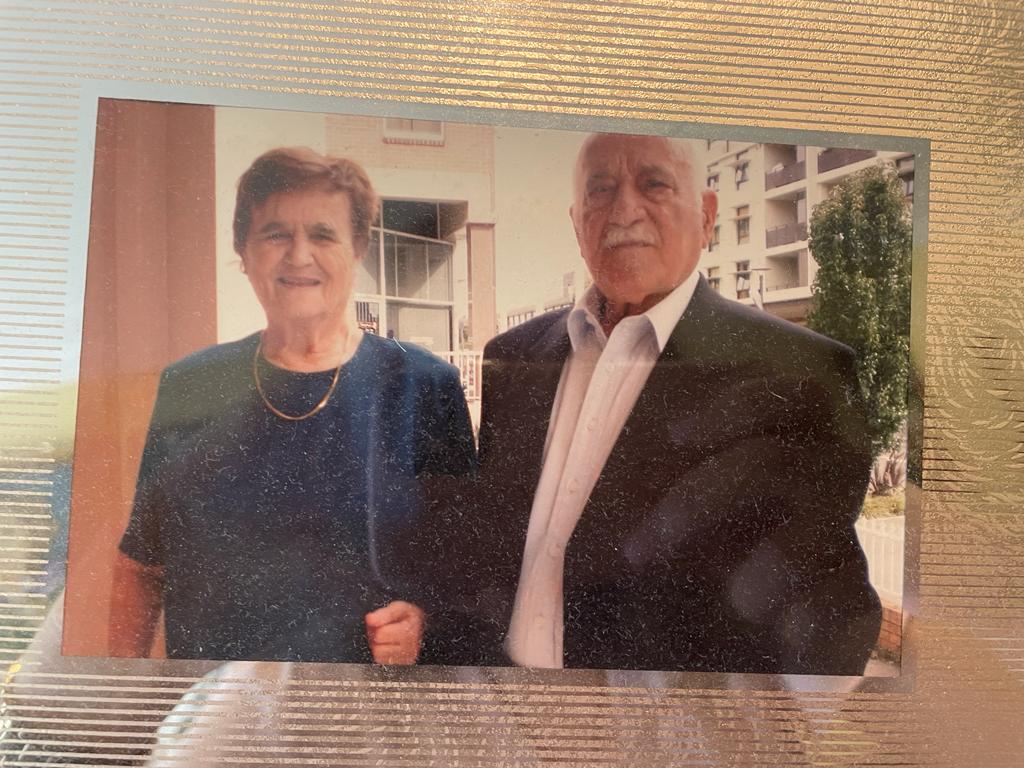

For Mr Bouris, the remainder of his life was tainted by memories of the massacres, but he was one of the lucky few who were able to get married and have children of their own.

After fighting in the Greek Civil War against the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) in the late 1940s, he continued to live in Kerpini for a few years until he met and married his late wife Georgia on May 10, 1953.

The couple eventually migrated to Australia as assisted migrants, staying for a short period of time in the Bonegilla Migrant Centre in Victoria. They later moved to NSW and stayed in suburbs such as Scone and Newcastle before settling in Sydney in 1959.

Mr Bouris and his wife had two children and four grandchildren and he said they lived a great life together in Australia. His home in the south-west Sydney suburb of Punchbowl is a testament to their love, covered with black-and-white photos of their life and family.

When I asked the 99-year-old whether he ever returned to Kerpini and what that experience was like for him, his answer was sad but realistic.

“I wanted to fix up my ‘patriko’ house, but everything was destroyed,” Mr Bouris said with a sad smile.

An indicator that whilst the Kalavryta Holocaust was 80 years ago, the atrocities of the Germans during WWII have left an unforgettable mark on those left behind.