Giorgos Lygouris turned 104 on 20 January, celebrating the occasion with cake, balloons, and his five children and their partners, 14 grandchildren and 22 great-grandchildren, all quietly convinced he may yet live to see a great-great-grandchild.

Ask him about the milestone and he responds with a shrug and a quiet smile.

“He has always been this way. No fuss. No complaints. No drama. Not about pain. Not about illness. Not about life,” says his daughter, 3XY radio presenter Mary Tsimikli-Economopoulou. “

The birthday was hosted by The Alexander Aged Care Centre in Clayton, where Giorgos has lived since November 2024.

“Before that, he was living independently in his Springvale South home, assisted by daily carers and daily visits and care by his children. He enjoyed cooking, tending his garden and playing cards, biriba, always without money, counting cards with incredible precision,” Mary says.

“He rarely took painkillers, he smoked until the age of 55 and quit only when the doctor frightened him.”

COVID never touched him, nor did loneliness as he was always surrounded by family.

Born into a broken century

Giorgios was born in Kalamata on 20 January 1922, the year of the Asia Minor Catastrophe, into a Greece fractured by war, poverty and political upheaval. For a man born that year, life expectancy hovered closer to 40 than 100, and survival beyond infancy was far from assured. Statistically, 20 per cent of babies born in 1922 Greece died before their first birthday.

That Giorgos is still here places him among a statistical rarity: one of fewer than 500 Australians estimated to be aged 104 or older today of which 75 per cent are women.

Across his lifetime, he has outlived wars, migrations, governments, heartbreak, and almost everyone who once knew him as a young man.

Law, resistance, and a vanished brother

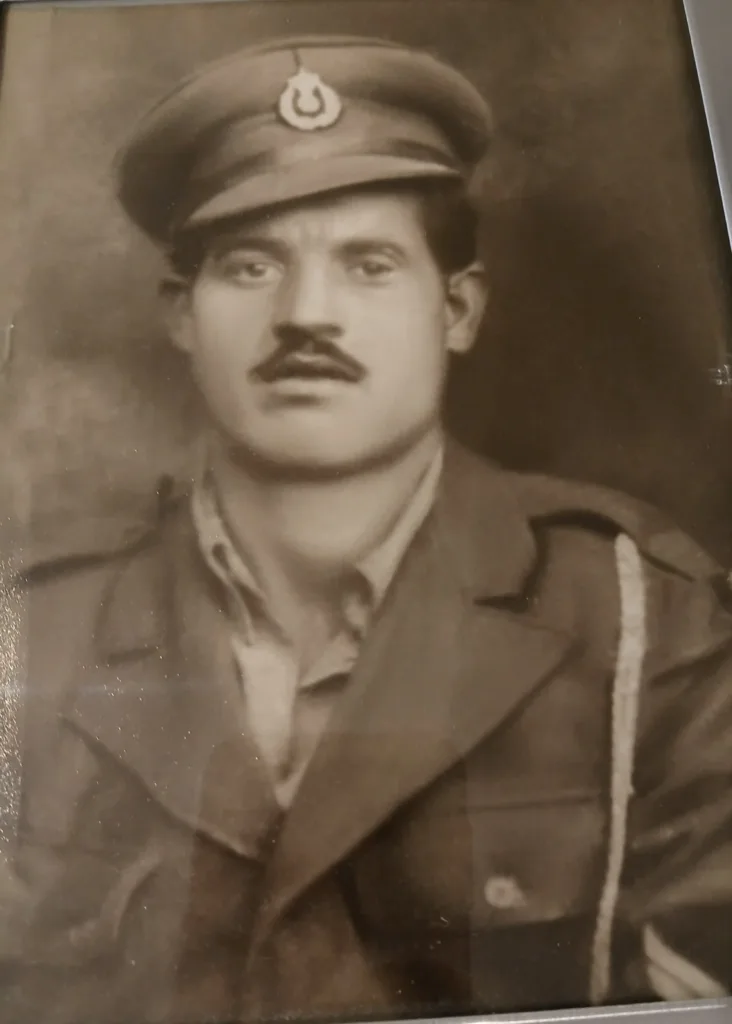

As a young adult, Giorgos became a χωροφύλακας, a rural policeman sworn to uphold order while Greece tore itself apart during the Civil War. History placed him on one side of the divide, and his brother Theodoros on the other.

“Theodoros was an antartis,” Mary says. “Dad was the law. His brother was the resistance.”

When Theodoros was facing arrest and trial, Yiorgos asked for a favour: not acquittal, just time.

“They held him for one night,” Mary says. “By morning, he was gone. They said he escaped, but no one ever heard from him again. We believe he was killed. My father felt betrayed.”

There was no body. No grave. No answers. Their mother unravelled, turning to psychics in her grief. Giorgos said little.

“He never spoke about it,” Mary says. “But it marked him.”

When his first son was born, Giorgos named him Theodoros after his lost brother. He never explained why. He didn’t need to.

Love, rules and survival

Marriage in post-war Greece came with conditions. As a χωροφύλακας, Giorgos could only marry if his bride brought a dowry. He eventually married Athanasia: a seamstress, sharp-willed and ambitious.

“He never called her Athanasia,” Mary says. “He called her koritsi mou (my girl).”

She drove; he never learned. She pushed; he steadied. Together they raised five children and pursued opportunity wherever it appeared.

They left their children in Athens and migrated alone to Germany. They worked. Endured. Returned. Then, in 1967, they all migrated to Australia under an assisted scheme, as Greece fell under dictatorship.

Mary, who was 12 at the time, remembers it clearly.

“Dad didn’t like Germany,” she says. “But Australia, that was different.”

The quiet grind

In Australia, Giorgos worked for decades at General Motors Holden. He never mastered English, just enough to get by.

“That was the only job he ever had here,” Mary says. “And he retired from there.”

Despite strong Kalamatian networks in Melbourne, he avoided community politics.

“He avoided associations,” Mary laughs. “Everyone wanted to be president. He went once and never went back.”

Loss without bitterness

Athanasia died almost eight years ago, and Mary remembers her father truly breaking then, as well as when he lost his granddaughter.

Yet even then, he did not harden.

These days, his sentences are shorter and he avoids phones. He sings instead: Dalaras, Parios, Dionysiou.

At the Alexander Aged Care Centre, Giorgos moves with a four-wheel frame, chooses his activities carefully and participates only on his own terms. Greek Café Days lift his spirits. Occasionally he joins in during sing-alongs of Greek songs. Familiar language. Greek films and, of course, cards.

“He plays strategically,” Mary says. “Counting hands, holding back, knowing exactly when to drop the ace.”

Until recently, he read everything — The Greek Herald, Ta Nea, Neos Kosmos, Ellinis. Greek-Australian media mattered deeply to him, including the world his daughter would later enter.

As a young journalist, Mary would collect freshly printed copies of The Greek Herald from its Gibb Street press publisher Theo Skalkos operated in Melbourne. She would take them straight to her father.

Through her, Giorgos is also linked to a formative chapter of Greek-Australian broadcasting. Mary worked under Skalkos when he bought Elliniki Ypiresia in Carlton and later founded The Voice of Greece.

His children once asked him if he regretted coming to Australia.

“This is a question I should ask you,” he said.

They told him the truth, that they would not change a thing.

“Then I don’t regret coming,” he said.

He has survived by saying little, enduring much and loving deeply; a quiet outlier in the statistics, and a giant in the lives that gathered around him this January.

If that is not a life worth celebrating, nothing is.

Another century marked

Giorgos was not alone in marking a remarkable milestone. Late in January, Mrs Georgia Sofatzis celebrated her 100th birthday, surrounded by family and memories that span Greece and Australia.

To mark the occasion, Mrs Sofatzis was visited by the Consul General of Greece in Sydney, George Skemperis, who congratulated her and thanked her for her longstanding contribution to her family and the Greek community. During a particularly moving meeting, she shared moments from her life in Lemnos and Australia, and recited beloved Greek poems.

Together, the two milestones offered a quiet reminder of the generations of Greeks whose lives have bridged hardship, migration and belonging – and whose stories continue to shape the fabric of Greek-Australian life.