By Dr Themistocles Kritikakos, University of Melbourne.

100 years later, the trauma that Greek survivors experienced during the final years of the Ottoman Empire has been passed on to their descendants living in contemporary Australia. The Armenian genocide during the First World War is internationally known. However, the similar experiences of Greeks and Assyrians in the late Ottoman Empire between 1914 and 1923 remain largely unknown.

In 2007, the International Association of Genocide Scholars (IAGS) recognised that the Ottoman campaign against Armenians, Assyrians, and Greeks between 1914 and 1923 constituted a genocide. The three groups experienced death marches, starvation, massacres, labour battalions, sexual violence, and forced conversion.

Approximately 3 million Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians died. The Greek Orthodox population in the late Ottoman Empire lived in Asia Minor, Pontos, Eastern Thrace and the Levant. The Greek minority were known as Romioi and it was a term that referred to their Byzantine heritage.

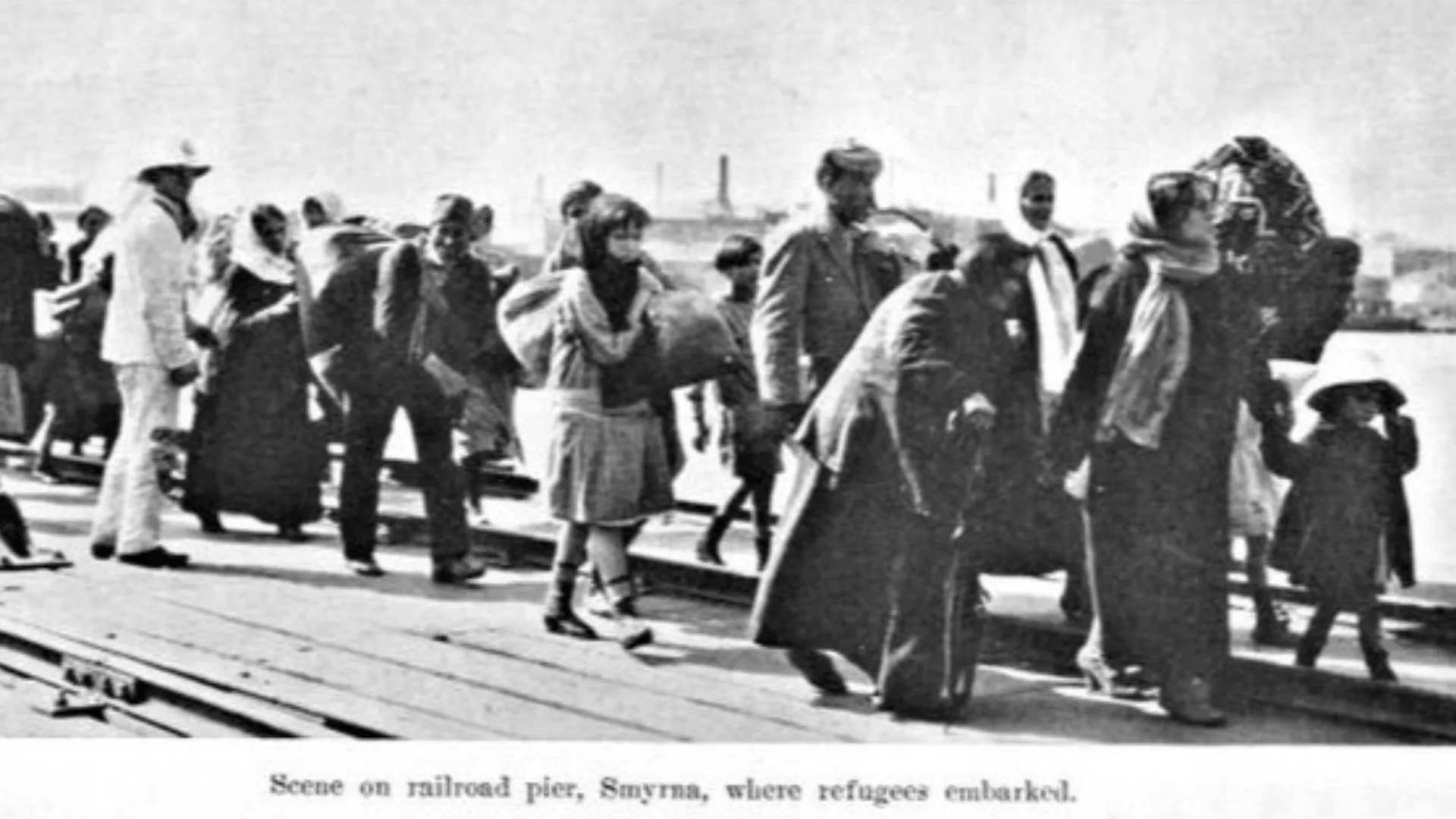

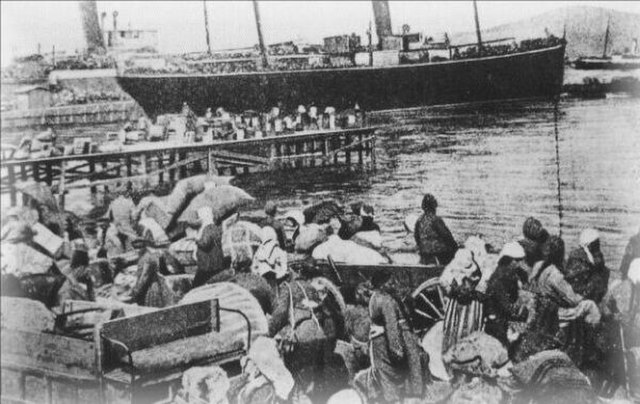

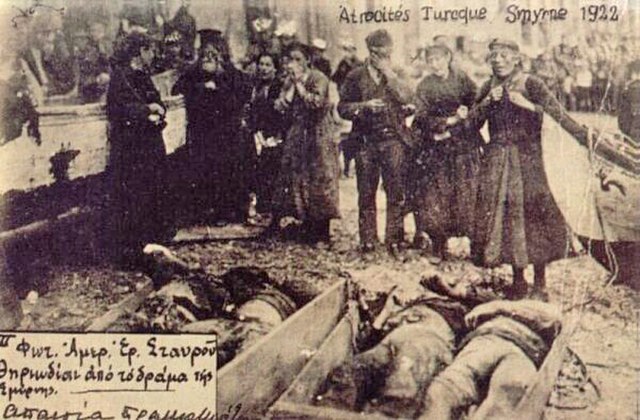

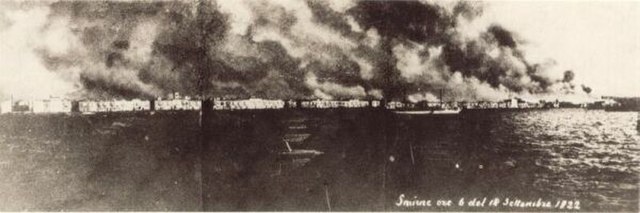

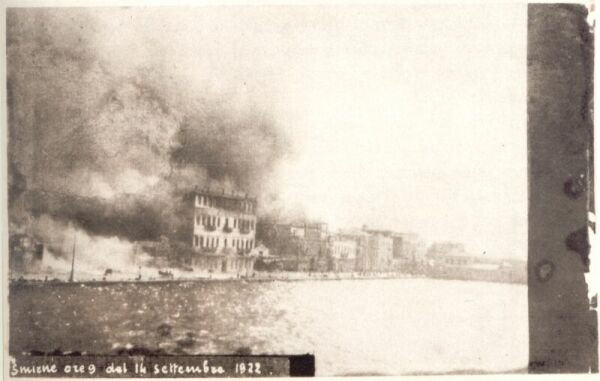

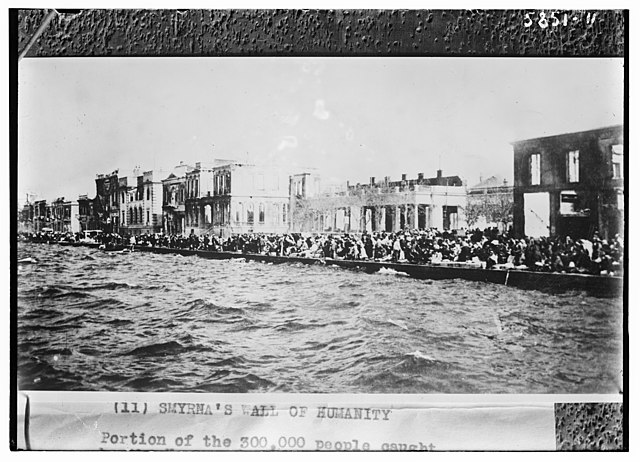

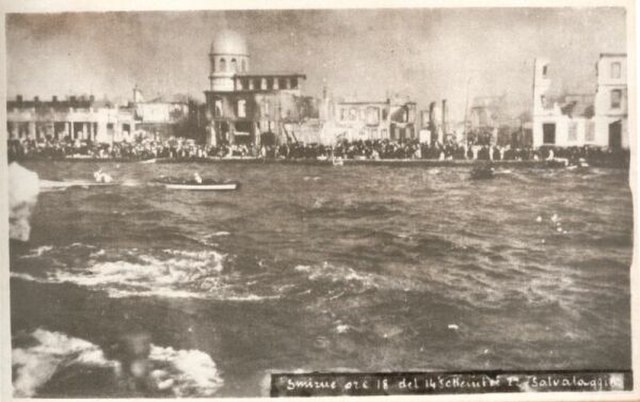

The Catastrophe of Smyrna in September 1922 was the burning of the Greek and Armenian quarters of the cosmopolitan city. There were approximately 100,000 Greek and Armenian victims. The Catastrophe was an event that took place at the end of a broader period of violence and uprooting experienced by the Greek population living in the late Ottoman Empire.

The Catastrophe of Smyrna led to the end of the Greco-Turkish War (1919-1922). This was followed by the Population Exchange, where around 1.5 million Christians from Turkey were transferred to Greece and 500,000 Muslims from Greece were transferred to Turkey. The Treaty of Lausanne was signed in 1923, which shaped the borders of modern Greece and Turkey.

During my PhD, I conducted over 70 interviews with Greeks and Assyrians in Australia. Usually, the survivors did not speak about their experiences due to trauma. It was easier for them to forget what happened.

“I never heard anything. Speaking about it would mean going back and experiencing it all again, which would have been extremely traumatic for them to do that,” explained a Greek interviewee with origins from Smyrna. The second generation did not ask the first generation about their experiences, and they did not discuss this with the third generation. Greek Orthodox refugees faced discrimination when they resettled in Greece. Greek survivors and, in some instances, their children, lived through the Second World War and the Greek Civil War. With migration, the events were forgotten, and they tried to re-establish themselves in a new country. They also wanted to protect their children. Due to the “double wall of silence” between the first and second generations, the trauma of the first generation was passed on to subsequent generations. The third generation tried to find out about the violence and uprooting their ancestors experienced. The descendants of survivors still ask how many relatives they lost and how many they never met.

If there were any discussions, it would be in the form of storytelling. An interviewee whose grandparents were from Vourla, in the province of Smyrna, remembered a family conversation that she heard as a child. Her grandmother referred to “our lost places” and mourned for a place called Smyrna. It was only during her adult years that she became interested in their family history and understood why her grandmother mourned. “I never understood why she was so sad about those lost lands, but now I know,” she said.

21 allied ships in the port of Smyrna received instructions to take a neutral position and did not intervene, but only rescued their own citizens. A Greek interviewee with origins from Smyrna recalled his father’s struggle to survive. “There was a ship. They swam close to it. They asked the British to save them. They asked, What are you? He responded, Greek. He escaped by hiding near the bottom of the ship. The Englishman on the boat had an axe and was ready to cut their hands if they were to come onto the boat. They didn’t want them.”

The stories of survival remain alive and resonate in the Greek-Australian community. A Greek interviewee with origins from Alatsata, in the province of Smyrna, remembered her father’s testimony. He was a child, and they separated the men from the women and children.

“They worked them to death without food, without water and he did not know where his father went.” she stated and continued, “They transferred them into a Church where they held them for days and they did not know what would happen next. Every night the soldiers would search for girls and they would rape them in the altar. He also saw the piles of dead bodies at the front of the church.”

The interviewee returned to Alatsata with her father to visit his childhood home and school. Her father relived the trauma that he had experienced as a child. It was only in his old age that her father discussed some of the events that he had experienced. The interviewee felt a sense of responsibility to write about her family history and her father’s experience.

Days of Remembrance

There are three days of remembrance for the Greek victims. In 1994, the Hellenic Parliament dedicated May 19 as a day of national remembrance for the genocide of the Greeks of Pontus, and in 1998, it dedicated September 14 as a day of national remembrance for the genocide of the Greeks of Asia Minor. September 14 is associated with the Catastrophe of Smyrna, but it is also a day of remembrance dedicated to all of the Greek victims in Asia Minor.

In 2006, at a Pan-Thracian congress in Didymoteicho, April 6, known as Black Easter, was recognised as a “day of remembrance for the genocide of the Greeks in Eastern Thrace”. The days of remembrance represent different events and identities based on region. In Australia, a shared experience has started to develop that represents all Greek victims.

In 2012, The Asia Minor Historical Society in Brisbane and the Greek Orthodox Community of St George, Brisbane organised an event for the 90-year commemoration of the Catastrophe of Smyrna, which also honoured the Greek survivors from Asia Minor that resettled in Brisbane during the 1920s.

The commemorative event included a memorial service and wreath laying ceremony to honour the memory of the Christian victims in the Ottoman Empire, the victims of the Catastrophe of Smyrna and the martyrdom of the Metropolitan of Smyrna, St Chrysostomos. Commemorative events for the Catastrophe have been organised in Sydney since 2016 and in Melbourne since 2017.

A Greek interviewee with origins from Alatsata, Smyrna, explained that “all Greeks were victims of genocide”, but the Catastrophe of Smyrna was commemorated separately because it was “one final blow” and “erased 3,000 years of Greek presence in what is today known as Turkey.”

December 9 is the day the United Nations adopted the Genocide Convention in 1948. Since 2015, it is an International Day of Commemoration which honours all victims of genocide. In Australia, the day of remembrance has become connected to the memory of Greek victims. Greeks in Melbourne and Sydney have also collaborated with other victim groups such as Indigenous Australians and the Jewish community.

It is also known that Australians provided humanitarian aid to Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian survivors and refugees between 1915 and 1930. Australian humanitarianism is the link that connects the Armenians, Greeks and Assyrians to modern Australia, while the descendants of the victims and survivors believe that their ancestors should be part of Australian historical memory.

The genocide is the cornerstone of the Armenian identity. The movement for recognition of the Armenian genocide started during demonstrations in 1965 in Soviet Yerevan. The criticisms of the Asia Minor Campaign (1919-1922) in the Greek political and historical spheres have led to silence on the matter of genocide without consideration of the broader period of violence between 1914-1923.

The efforts of Pontian Greeks to achieve genocide recognition started in the 1980s. The recognition efforts were associated with the revival of Pontian Greek culture and represent a distinct trauma. The memories of Greeks from other regions of the Ottoman Empire, such as Asia Minor more broadly and Eastern Thrace, have often remained in families.

Greeks and Assyrians have cooperated with Armenians to try and achieve genocide recognition from the Australian Federal Government. Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians have a shared experience. Joint recognition was achieved in 2009 in South Australia and in 2013 in New South Wales. However, the unresolved traumas of survivors haunt subsequent generations today.

READ MORE: ‘We will not forget’: NSW and SA communities mark anniversary of Greek Pontian genocide.