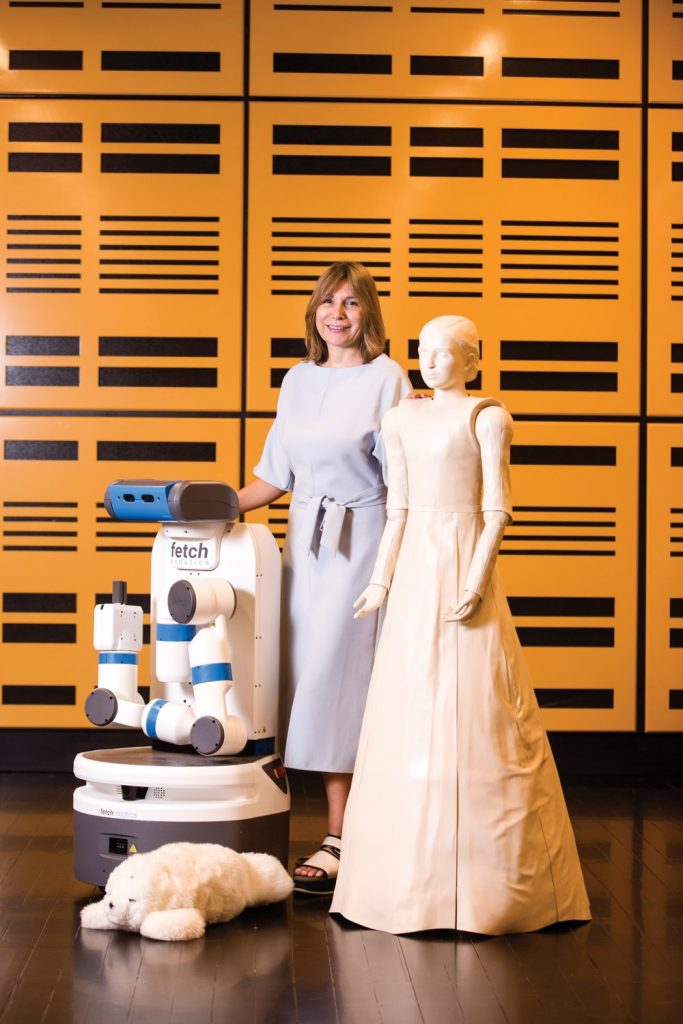

Mari Velonaki is a researcher in the field of robotics and she shares with The Greek Herald how machines can be applied to many everyday life scenarios to make things much easier and help us move towards a more inclusive society.

Mrs Velonaki is a highly distinguished expert in the area of human-robot interaction. She is one of the co-founders of the Centre of Social Robotics and the Director of the Creative Robotics Lab. She was also a major contributor of the “Fish-Bird: Autonomous Interactions in a Contemporary Arts Setting” project in 2003. And these are but a few on the long list of her achievements.

Speaking to The Greek Herald, Mrs Velonaki tells us why she first got into the field and what it was that attracted her interest:

“My undergraduate degree was in responsive systems, it was in a cultural context in media. So, after doing that for quite some time, I moved to robotics. Post my PhD, I was interested in working with physical agents that share the same space (with people),” she says.

“I started working in robotics, I designed the first robot Fish-Bird in 2003 and my first academic position was at the Australia Centre for Field Robotics at the University of Sydney in the same year.

“So that was my transition from designing interactive systems to designing physical systems. I started social robotics in Australia in 2003. Up to that point, social robotics as a terminology didn’t even exist and now it’s become mainstream and that’s wonderful.

“What we identify as “social robotics” are robotic systems, designed with the public as a user. Not for experts, not for factories, but systems that are designed to interact with people, to interact with society in their daily activities and hopefully enhance those activities. Hopefully. We’re not there yet.”

But in what ways can robots further enhance our daily lives? According to Mrs. Velonaki and the work she’s doing with her team, there are many things that machines could help us with.

“Of course this is filtered by my own personal belief system but the three areas that we’re working on and we think robotics could be useful [in], are assistive technologies, culture and education, for example in museums [but not replacing teachers as part of learning] and the third one would be in human futures, which is a much bigger area,” she says.

“A near future robot, for me, would be an autonomous car for example. Because an autonomous car would have an agency, not now that we’re still in semi-autonomy, but the next generation that could scan outwards in order to understand how to move on its own, but also inwards, to see if people are comfortable in the car. I think transportation is one (area) within the human futures (field) which is also assistive.

“But assistive technologies could expand to other areas such as rehabilitation and that’s something that can be applied for all people. Again though, I would like to point out that I don’t believe that robots should replace people, so the model of an anthropomorphic robot that is your nurse or the neighbour that you don’t have is not the one that I believe in. Replacing humans is not what we set out to do, unless there’s a special reason for it, like safety for example.”

In order to move closer to such a scenario, where robots comprehend human emotions to such an extent that they operate in response to them, there’s a fear within some people that these machines may begin to gain their own level of consciousness.

But the robotics expert doesn’t put much weight on such a hypothesis.

“I don’t think that robots are becoming more responsive to human emotions. When we talk about human emotions and social robots, emotions are with double quotation marks. Machines don’t have emotions,” Mrs Velonaki says.

“I know there’s all these other fields of technology and people who are asking “are they learning?” Look, everyone has a preference but, realistically, I don’t believe a machine can have emotions. That’s why I don’t believe in “evil” AI or “evil” robots.”

As for the one thing that she hopes to achieve by the end of her career, Mrs Velonaki has a very important goal in mind:

“My vision with the national facility is to create systems that enhance our experiences, that are playful, not strictly utilitarian, that embrace our humanity, what it means to be a person. Even when you use machines that are creative,” she says.

“But I would also like to see an expansion of what we presume as a public space by making room for people from various areas such as different age groups, different disabilities, etc, to partake and feel that they belong, that they’re not the ones with the difficulty and get that sense of inclusion from these spaces. Because all of us have abilities and disabilities and things we can and cannot do and that’s where the field of robotics comes in and helps to fill that part in.”