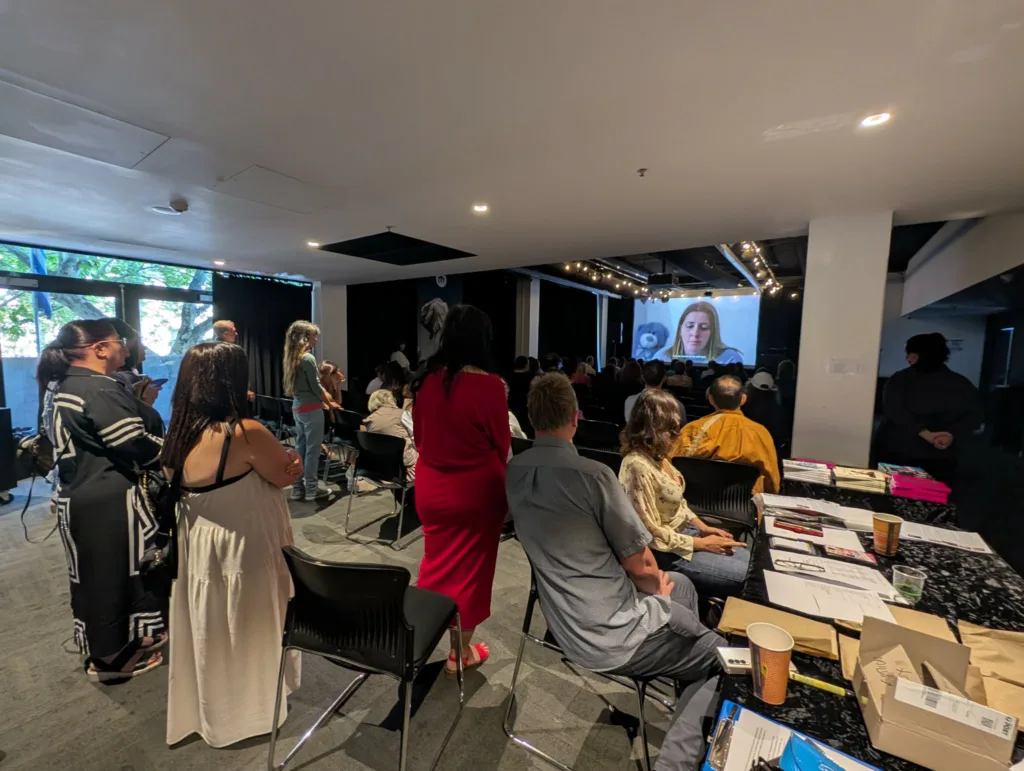

At the Greek Community of Melbourne’s (GCM) Greek Centre, the silence finally broke.

Greek Women Speak, a symposium created and moderated by poet Koraly Dimitriadis, tackled subjects migrant families avoid: rape, domestic violence, workplace bullying, dementia, queer identity, and more.

Subjects politely buried at baptisms and barbecues saw light of day, and the message was clear: misogyny is neither abstract nor imagined; it is lived experience.

“Today is a day of conversation that our culture prefers to shove under the rug,” Dimitriadis said. “Today we say enough. We are not going to carry the shame and the guilt anymore… because [society wants] to portray perfection.”

Author and media professional Nikki Simos shared a story she carried alone for decades.

“When I was 17, I was raped… twice. One was 25 years older than me, the other closer to my age. I was groomed and didn’t realise it at the time. Carrying this secret and a subsequent abortion for 30 years, I shielded my family and community. I don’t forgive the act, but I forgave the person to find peace. Forgiveness was about freeing myself,” Nikki said.

Domestic violence advocate Jo Galanis described surviving what she called “domestic terrorism.”

“I met my perpetrator when I was vulnerable. Within six months, there was the first violent incident,” she said, recounting verbal abuse, physical assault, financial control, and sexual coercion.

She reflected that the relationship pushed her to a breaking point. A psychologist helped her realise the problem was the relationship, not her.

“Stop the judgment that keeps women trapped,” Galanis urged.

Shame and guilt keep women trapped, said lawyer and anti-bullying activist Stefanie Costi. She thought carefully before telling her story.

“I worried speaking out might end my career,” she said. “Silence is complicity. I refuse to be complicit any longer.”

The conversation extended to the broader Greek Australian experience. Poet Petr Malapanis addressed ageing and desire, describing the ageing body as a “revolution until the last breath.”

Mental health advocate Stella Andrianna Michael, who runs Patris in Brunswick and supported the event with catering via Grazing with Stella, highlighted the gap between clinical frameworks and migrant realities, where cultural stigma can wound as deeply as illness.

Media personality Roula Krikellis told The Greek Herald, “Fear keeps women small, but communication is key to change. Women must understand that their voice matters.”

Other speakers included lawyer Emily Highfield, Eleni Psillakis, who supports people post-release from prison, and queer Australian creator Kat Zam.

Building safety hubs

During breaks, clusters of women cried, laughed, and exchanged numbers; courage became contagious.

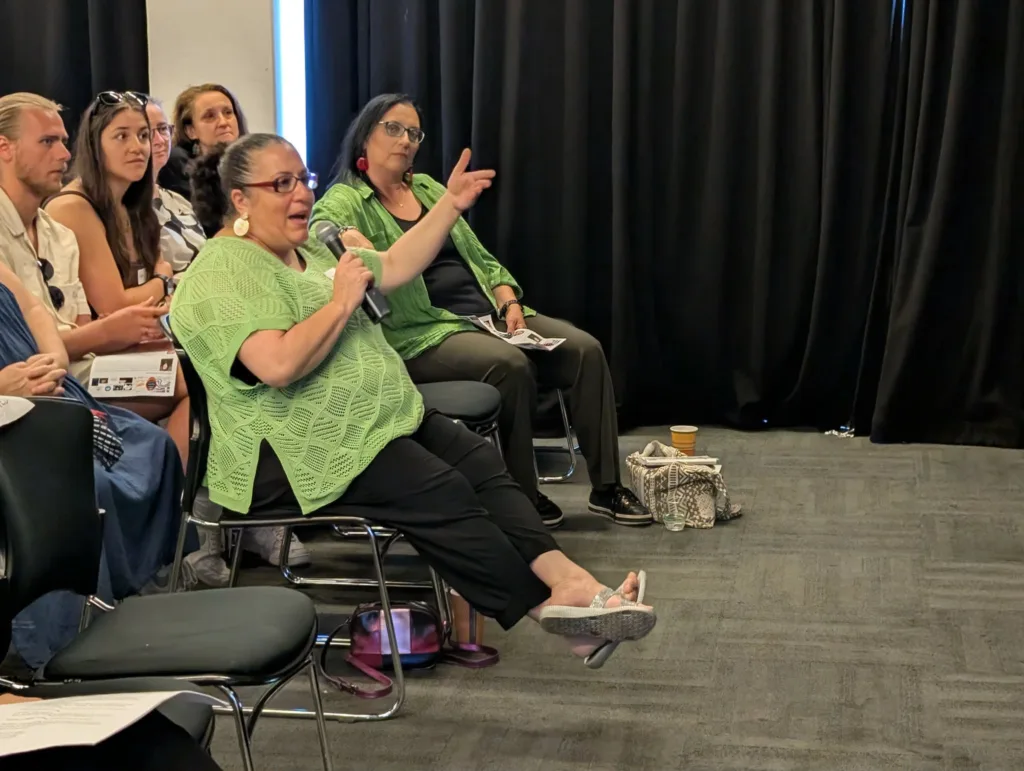

Community member Ara Markopoulos shared the brutal side of traditional loyalty, recounting how her Cypriot mother-in-law responded to her abuse with “Kala sou kanei,” (“serves you right”) suggesting she deserved the violence even after losing her pregnancy and suffering head trauma from domestic violence.

“I went to Greek Australian welfare organisations and they didn’t help,” she said, giving names of groups that never returned her calls. “I eventually received support through Heidelberg Women’s Group for domestic violence. I was so lucky to find them.”

One older woman in the audience took the microphone to note that we should not stigmatise Greek Australian men who are no more prone to a rape culture than the mainstream.

The stories, however, were powerful. Greek words like patriarchy, misogyny and even a mythological god-sanctioned rape culture from the days of Zeus who raped Europa, Poseidon who violated Medusa, Daphne who fled Apollo’s advances and so forth.

Queer director and Joy Radio host Demetra Giannopoulos reflected on generational shifts.

“All these topics need to be discussed. It’s wonderful to see many generations, many perspectives. Women’s voices have not been heard enough. From a queer perspective, we aren’t heard enough. We need to overcome Gen X issues,” Demetra said.

“Ageing, aged care, and medical responsibilities are real pressures. People are staying alive longer. You’ve got to start somewhere, and I expect many of the women here will speak to their partners and mothers. There are a few men here, and as these events become more common, more men will come. I have faith in our Greek men. They try. Maybe this event opens up conversations.”

Attendee and Food For Thought Network member Helen Karagiozakis said she was drawn to the diversity of voices.

“We often hear stories of success and hope, but alongside them sit stories of loss, despair, and trauma. I’m here to support people sharing their stories and to create space for everyone to be heard,” Helen said.

Reflecting on her upbringing, she added, “I grew up in a household with cultural ideas that were dated. While I don’t relate directly to every story, the themes of loneliness and trauma alongside achievement resonate. I want to help people share, and maybe in time I can share my own story.”

Storytelling heals

Katrina Lolicato, from Arc Up Australia, a storytelling studio she runs with her sister, noted the importance of supporting Dimitriadis.

“We’ve been following her work for 10 years. Particularly for post-war migrant women, there was no place for critical discussions about policy gaps and lived experiences. Old ideas take a while to shift, but events like this help,” Katrina said.

“We’ve learnt to push boundaries, have better jobs, and are no longer cleaners. That doesn’t free us completely, but it gives us more influence and agency to create change.”

She added that while migrant women are entering community organisations, they are often present only to vote, make coffee, attend events, and make the group appear represented. “But the real influence isn’t there. Institutionalised perceptions are strong to change.”

Her 10-year-old daughter Nina shared her perspective.

“I find it cool to hear what women are achieving,” she said. “In the playground, boys always say they’re better, but I tell the teachers and sometimes tell the boys it isn’t fair. Things can be done.”

The status quo can be challenged.

One instance of this was evident in the Australian premiere screening of TACK, produced by the Onassis Cultural Centre and directed by British-Greek filmmaker Vania Turner. The film follows an Olympian who sparked Greece’s MeToo movement as she inspires a younger sailing champ Amalia Provelengiou to break her silence after being groomed and sexually violated by her coach when aged 12.

As Dimitriadis said, the fact that the conversation is happening and ruffling feathers is a vital step forward. The performance of perfection is over, and real dialogue has begun.

Without gatekeepers or silencing forces, just women in solidarity sharing their experiences, the room became a space of courage and conversation, but the question remains: will it bring lasting change?