As Greeks, many of us grow up hearing phrases like “to ksylo vgike ap’ ton paradeiso” (“violence came from paradise”) or “tha sou valo piperi” (“I’ll put pepper on your tongue”). Said jokingly, almost affectionately, they hint at something deeper: the normalisation of tough discipline and, at times, violence in our families and institutions.

When the UN declared 25th November as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in 2000, Liana Papoutsis had just entered a violent relationship. As a human rights lawyer and family violence prevention specialist, she has spent the last 12 years advocating for the elimination of gender-based violence. Her lived experience informs her advocacy.

“When we look at community institutions, faith spaces, cultural associations, most are male dominated. That doesn’t automatically mean more violence, but it does influence how visible and acceptable sexism can be,” she says.

Hidden family violence

Papoutsis is clear that Greek Australian communities are no exception to national trends. “Why would we think the Greek community is exempt from something affecting all of society?” she questions.

“We know family violence is very much present, but it remains in the shadows due to stigma and fear,” she says, concerned that it is swept under the carpet in a way that prevents it from being addressed.

When conversations were proposed for Greek language schools, she was told parents would object. She approached a leader of a Greek community organisation to request participation in a research project.

“I explained our project on preventing family violence in faith communities. He said someone would get back to me, but nobody ever did,” she says.

Welfare organisations see the reality up close. “Openly acknowledging it can cause unrest,” Papoutsis says, adding her academic research into violence prevention in faith communities also revealed resistance.

“Priests were similarly divided between denial, some telling me ‘there’s no problem in the Greek community’ and helplessness, where they say: ‘If someone tells me something, I just send them to the police.’”

A personal survival story

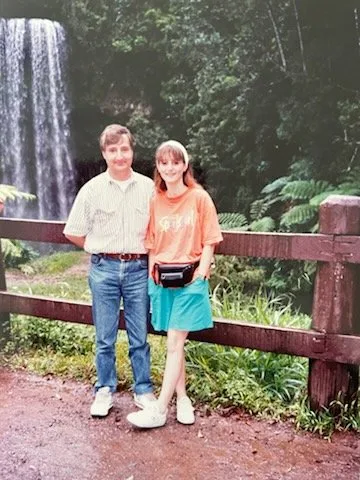

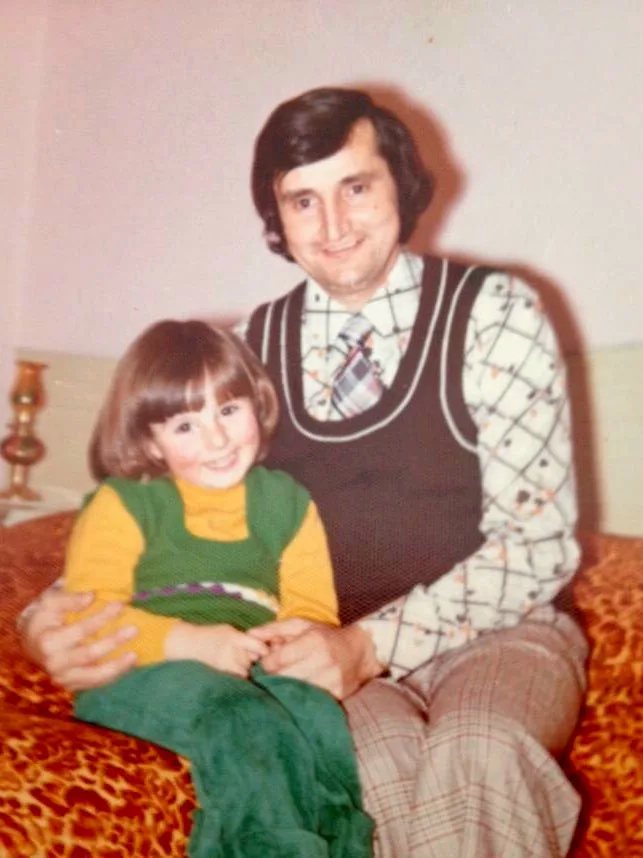

Papoutsis speaks with measured clarity, but her calmness sits atop years of trauma.

“I’m Greek Australian. Educated. Born here. And I lived through 14 years of abuse,” she says.

What began with “small lies” grew into financial control, coercion, threats, and physical violence. The breaking point came when her former partner harmed their child and issued death threats.

“That was it. Everything became about protecting my son,” she says.

At the same time, her father— an activist, resistance fighter, and her greatest supporter — was dying. She had hoped to spare him the truth, but her perpetrator reached him first, twisting the narrative.

“That incident caused a lot of pain, but my dad and I resolved it. His dying words to me were about staying safe,” she says.

Even after escaping, judgement followed.

“Perpetrators are often ‘street angels, home devils’. People couldn’t believe it. Some in his family told me it was my fault he went to jail. Instead of supporting a traumatised child, they supported him. Deep down, though, they knew,” she says.

Microcosm of society

Papoutsis notes that migration stories, intergenerational trauma, language barriers, and patriarchal norms all contribute to the silence around violence in Greek Australian families.

“Our migration story is coloured by hardship. Reporting is lower among CALD women. Shame is powerful. Many families instruct women not to ‘embarrass’ the family. Patriarchy, silence, and the lack of women in leadership make challenging abusive behaviour even harder,” she explains.

Young Greek Australians, she says, are trying to break the cycle, but not without backlash. “There is progress, but also real resistance. And we must talk about that honestly.”

Responding to the situation of younger women experiencing coercion in Greek Australian community groups, she says: “We need parents to stop enabling bad behaviour from sons. We need accountability.”

Crucially she emphasises that men must be part of the solution. Not to take over the table “but to buttress the women who are already speaking. Men as allies matter,” she says.

Change in workplaces

Workplaces, she says, mirror society, and Greek Australian environments may be a little slower when it comes to adopting change.

“You will have perpetrators and victims in every workforce. Companies must act decisively. Too often, people call someone a ‘bully’ without naming the behaviour as violence or coercion,” she says.

Papoutsis was especially proud to take part in the recent launch of Relationship Matters’ Safe and Supported at Work program. The innovative program integrates confidential counselling with specialist legal support and is offered to employers who want to support employees impacted by family violence.

The program was launched by the Assistant Minister for the Prevention of Family Violence Ged Kearney, with Relationship Matters’ CEO Maya Avdibegovic leading the presentations on the program. The launch was organised by Relationship Matters’ Business Development Manager Vicki Kyritsis, who is also the Vice President of the Greek Community of Melbourne and Victoria. Vicki oversees the program.

“This program equips employers to meet new legislative obligations and provide trauma-informed, culturally sensitive support,” Papoutsis says.

She notes that Victoria has led the nation on reform.

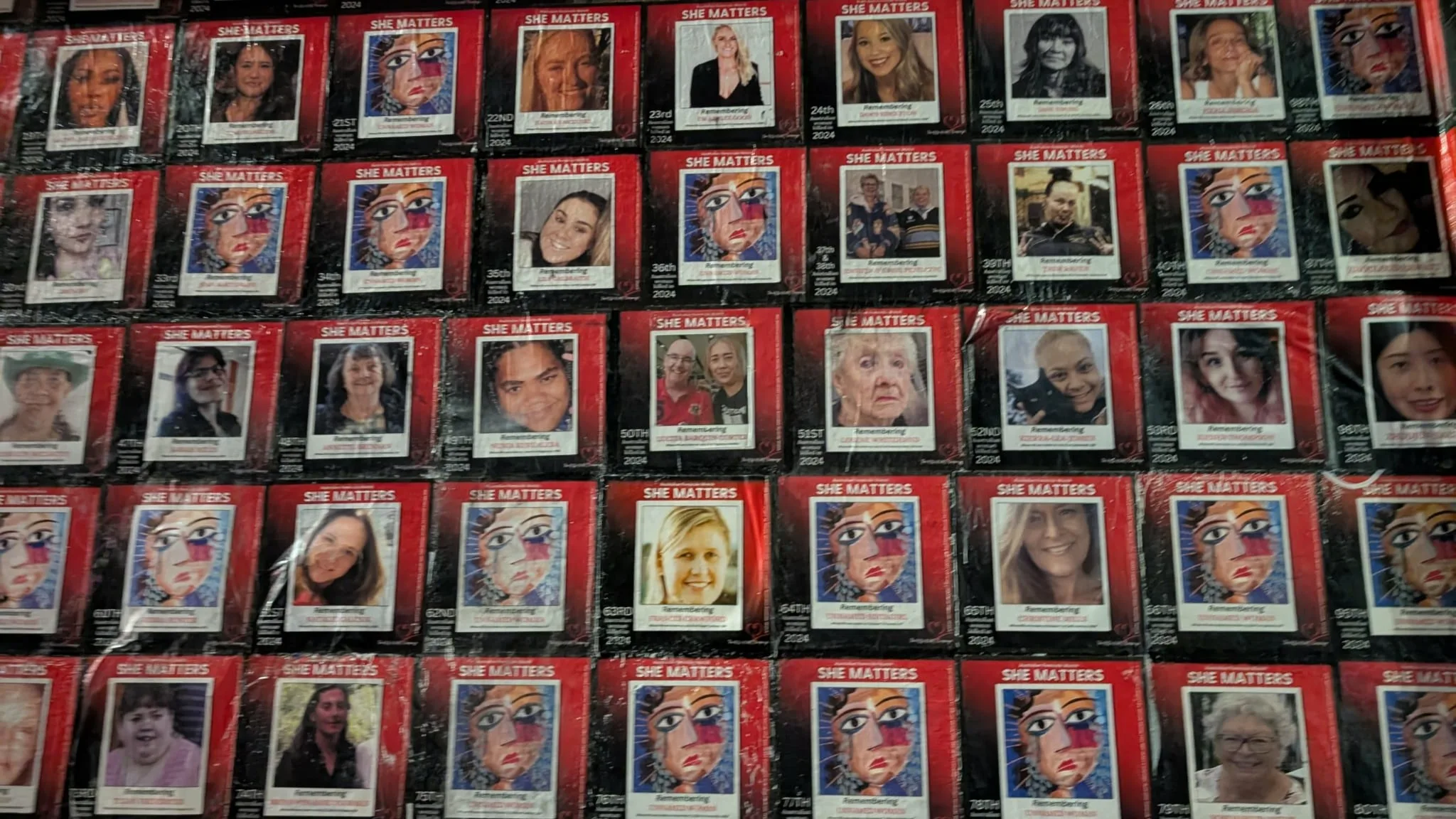

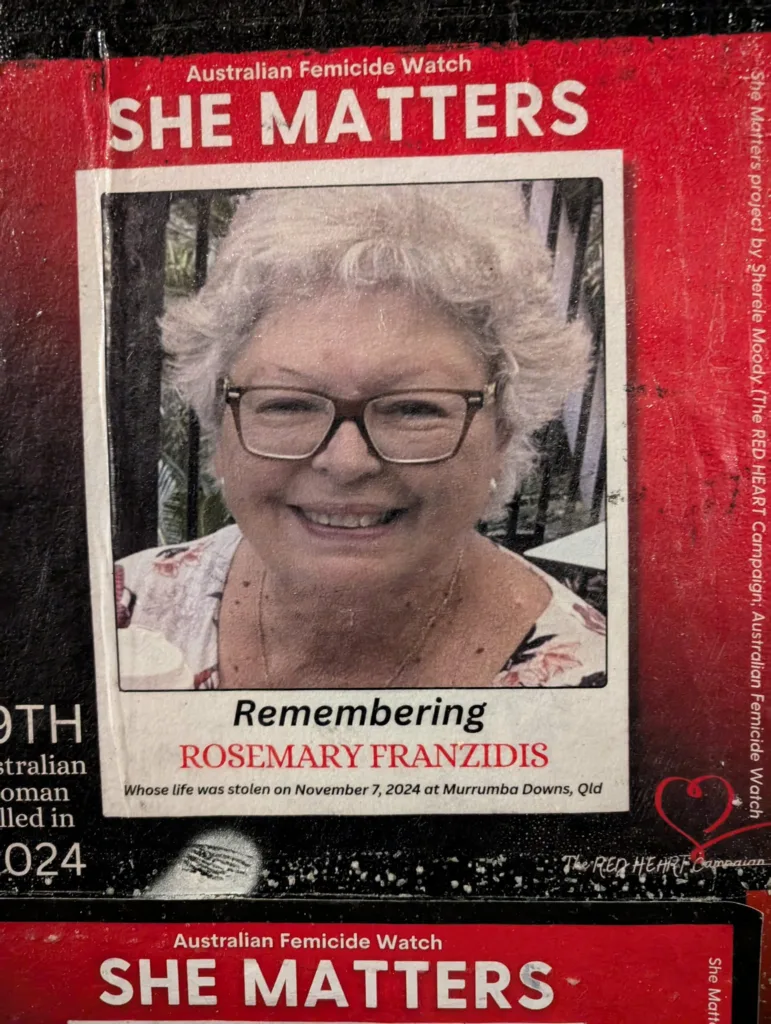

“I’m proud to be Victorian. The investment and lived-experience leadership model is world-leading. But this is a national crisis. Over 50 women are killed each year. If this were terrorism, billions would be spent,” she says.

She argues that lived experience must remain central. “We used to build systems and expect survivors to fit into them. Now we co-design with them. That’s how real change happens.”

Holding on to hope

Despite everything, Papoutsis radiates strength. “I’m in the best place I’ve ever been. My son is 20 now. I’m teaching him about respect, about the kind of man he wants to be. What we went through doesn’t define us.”

Her message for 25th November is straightforward.

“Family violence is happening in our community. We need honesty. We need leadership. And we need to stop pretending tradition is an excuse. We are a long-established community in Australia. There is no excuse for silence.”

To find out more about Safe and Supported at Work, employers can contact Vicki Kyritsis at workplacematters@relationshipmatters.com.au