John first went to Australia in his mid-twenties in the 1990s with his Greek Australian wife, whom he met while she was on a working holiday in Greece.

They returned to Greece a few years later because, as John tells me: “The first two months seemed okay but after that, it became unbearable. Even though I was in a large capital city, it was dead. At 8pm it seemed like everyone was in bed! We’d go to a petrol station to drink coffee! I thought, ‘No way will I live here’.”

John adds that he found Australia to be “primarily a consumerist, materialist society.” He says this contrasts with his philosophy: “Life, not money. Friends to go out with in the evenings as we do in Greece, without having to make plans weeks in advance.”

Originally from a working-class suburb in Athens, John stresses that while finishing his degree in Engineering at a public university in Athens, he lived at home but worked as a waiter and in construction, managing to afford trips abroad “to Europe, Africa, South America and the USA, etc.”

He says, “I saw how other people lived and when they’d ask me where I was from and I’d say ‘Greece’, they’d say, ‘Wow, a Greek. You’re from a huge civilisation’.”

Then, after finishing his degree and military service, he practised his profession in Greece, making good money and even managing to pay off a new car quickly.

“In Australia, though, my wife and I tried to open up a small food business, but we never had any money to go out and enjoy ourselves! That also led us to deciding to go back to Greece again a few years later, with only 500 dollars in our pockets,” he says.

John then describes how it took the couple only a few years to set up their lives in Greece again. “I went back to my profession and my wife worked in a tourist shop. We eventually bought a small block of land, then built a house, had two children – and went back to Australia on trips to visit my in-laws.”

But alas, almost 20 years later, when the Greek crisis hit, the couple, with their then 15- and 16-year-old children, returned to Australia.

I asked him, “Why did you return to Australia since you disliked life there so much?”

He responded: “When the Greek crisis hit, we decided to go back to Australia for our kids’ education, for them to learn better English, plus my wife was homesick. I thought that the education system would be better in Australia, but it wasn’t. Our children encountered bullying because they didn’t seem to fit the ‘woke agenda’ and expressed their views.”

He adds, “Within this culture of ‘wokeness’, I even felt pressure not to say Merry Christmas, but rather ‘Happy Holidays’. Yet when it came to me finding work in my field, I had the door shut in my face. You see, I was aged 50 then, and ‘too old’.”

“It took me almost two years to get my engineer’s licence recognised in Australia. And even Greek Australians who promised to help me find work then ignored me when I called them. I had to work as soon as possible, so I attended a training college and completed a Certificate in Aged Care and worked in this field, which I enjoyed, but it made little money,” he says.

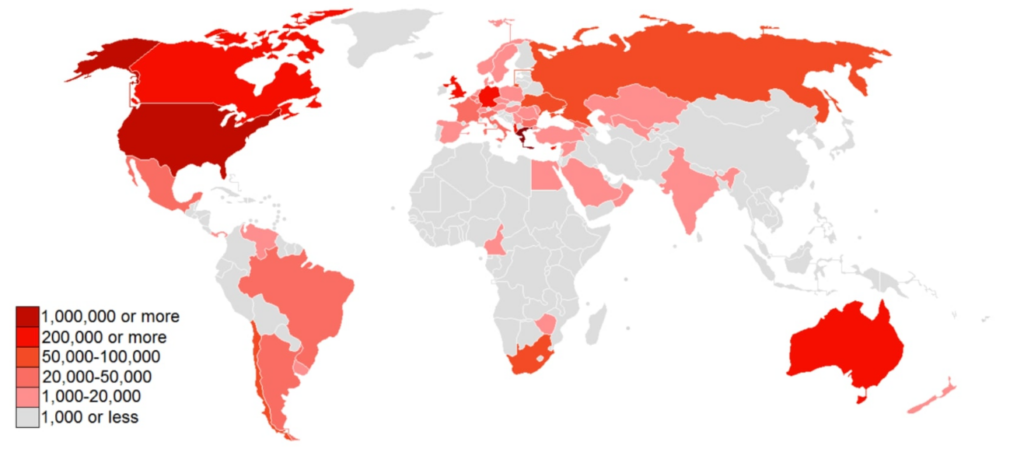

When asked about the Greek Australian community, John reflects that he found the first generation warm and welcoming, while the second generation seemed to be balancing between two cultures. He observed that their lifestyles and priorities were often shaped by the fast pace of Australian life, leaving less room for the kind of spontaneous social connections he was used to in Greece.

He notes that many people, regardless of background, appear to feel social and financial pressure to maintain a certain standard of living, which can lead to constant work and limited leisure time. For John, this seemed tied to what he perceives as a highly consumer-driven system that keeps individuals focused on earning and spending, often at the expense of relaxation and community life.

He also reflects critically on aspects of Australia’s welfare structure, suggesting that while it provides important support, it may inadvertently create dependency or encourage people to make financial choices based on benefits rather than long-term stability. Still, he is quick to acknowledge that these are complex social issues rather than individual failings.

He then frowns and sighs: “Look, I like Australia – like I like Paris, Rome and New York – for holidays. I couldn’t live there though. And I don’t criticise everything about Australia. Public buildings, parks, landscaping, schools and roads, and bike paths are good, but… houses are cheaply built.”

As our meeting comes to an end, John, a romantic at heart, says: “I have no regrets though. I did it for my wife because I love her.”

Reverting to form, he adds: “The second time in Australia saw us return to Greece again after five years. Even if they gave me 10 million dollars, I wouldn’t stay in Australia. Life is short – you only live once – and here I see the Greek sea, and the sun doesn’t burn! I’m blessed to live in Greece even though it is hard here. You see, Greece is for the brave.”