By Dr. Themistocles Kritikakos (Historian)

Last year, while navigating the chaos of traffic in Naples, our driver turned to me mid-conversation and said with conviction, “We have Greek roots, not Roman.” His words carried the voice of centuries, echoing the city’s ancient past.

Throughout its long history, Naples has been ruled by many powers, including ancient Greeks, Romans, Ostrogoths, Byzantines, Norman kings, Spanish and French rulers, and southern Italian dynasties, before becoming part of a unified Italy in 1861. Situated in the Campania region, the city maintains connections to its Greek foundations.

The first Greek settlement in Naples, established in the late 8th century BCE, was known as Parthenope. According to mythology, Parthenope was the Siren who threw herself into the sea in sorrow and ended her life after failing to captivate Odysseus with her song. Legend says that her body washed ashore at the site where the earliest settlement would emerge, and the first settlement was named after her.

Building upon this early foundation, Neapolis was formally established around the 6th century BCE by Greek settlers who had earlier founded the nearby colony of Cumae. Meaning “New City,” Neapolis was designed with an organised grid plan based on the principles of Hippodamus of Miletus, the renowned Greek urban planner.

Today, visitors walking through the historic centre and along Spaccanapoli, a narrow, straight street that runs through the old city, still follow street patterns laid out by the ancient Greeks. The indigenous Italic groups, including the Samnites and Campanians, inhabited the inland regions. They engaged with Greek settlers through trade, alliances, and periodic conflict, all of which shaped the region’s cultural identity.

The Campanian Greek Network

The Campania region in southern Italy was home to several important ancient Greek colonies, including Cumae and Poseidonia (present-day Paestum). These colonies were hubs of culture, commerce, and governance that promoted trade, helped spread Greek art and architecture, and encouraged the sharing of ideas.

Cumae, founded around the 8th century BCE by settlers from Euboea, was the first Greek colony on the Italian mainland and served as the gateway for Hellenic culture. Known for the Sibyl’s cave, it became both a spiritual and commercial centre. According to mythology, a priestess of Apollo delivered her prophecies from chambers within the cave, symbolising a gateway to the underworld and the connection between the mortal and the divine. Poseidonia, founded around the 7th century BCE by settlers from Sybaris (in modern-day Calabria), who originally came from Achaea, is renowned for its well-preserved Doric temples, which remain among the finest examples of Greek architecture anywhere.

Campania became a region characterised by a cluster of Greek settlements that contributed to the cultural and economic development of southern Italy. Nearby Pozzuoli (ancient Dicaearchia) served as an important port linking Campania to broader Mediterranean trade routes.

Together, these cities formed a trade network that sustained Campania’s prosperity by exporting both essential goods and luxury items to Greece, Sicily, and beyond. Naples, in particular, emerged as a vital maritime centre due to its strategic location and prominence as a cultural and commercial centre. This commercial activity grew further under Roman administration.

Tracing Greek cultural legacies

Unlike many cities of Magna Graecia conquered outright by Rome, Neapolis was captured by the Roman Republic in 327 BCE but then granted favourable treaty terms the following year in 326 BCE that preserved some degree of autonomy. Greek language, religious practices, and architectural forms remained prevalent, reflecting the continuity of Hellenic cultural traditions alongside Roman influences. During the early Christian and Byzantine periods, Greek-speaking communities remained active, maintaining links with the eastern Mediterranean that were crucial to the city’s evolving identity.

The Epicurean philosopher Philodemus of Gadara (from present-day Jordan) taught in Naples during the first century BCE, advocating for tranquillity through measured pleasure, friendship, and emotional understanding while making philosophy accessible to ordinary people. Philodemus’ writings, preserved in the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum, show how Greek thought endured well into the Roman period.

The Roman poet Virgil spent time in Naples, drawn in part by the region’s rich Hellenic environment and the peaceful atmosphere it offered, away from the political turmoil of Rome, which provided a favourable setting for his literary work.

When the sophist Philostratus the Elder arrived in Naples from Lemnos in the early third century CE, he encountered a vibrant cultural life characterised by public recitations, artistic engagement, and the continued use of the Greek language. Captivated by the city’s Hellenic environment, he chose to remain and compose his Imagines, a literary work describing mythological paintings displayed locally.

Centuries later, Naples still retained its Greek identity. During the siege of 536 CE by the Byzantine general Belisarius, the historian Procopius described the inhabitants as “Hellenes.” Reflecting on this, historian Edward Gibbon argues that the city had preserved its Greek character well into the sixth century. From the Roman imperial period through to the early Byzantine era, Greek language and traditions remained integral to Neapolitan cultural life, reflecting the city’s origins as the Greek colony of Neapolis.

Uncovering the past

Modern archaeological research continues to shed light on Naples’ Greek heritage. Excavations beginning in 1976 beneath sites such as the Church of San Lorenzo Maggiore have uncovered both Roman and earlier Greek structures, including markets, shops, ovens, and streets. In recent years, there has been increasing interest within the city in integrating underground remains into the fabric of the contemporary urban environment.

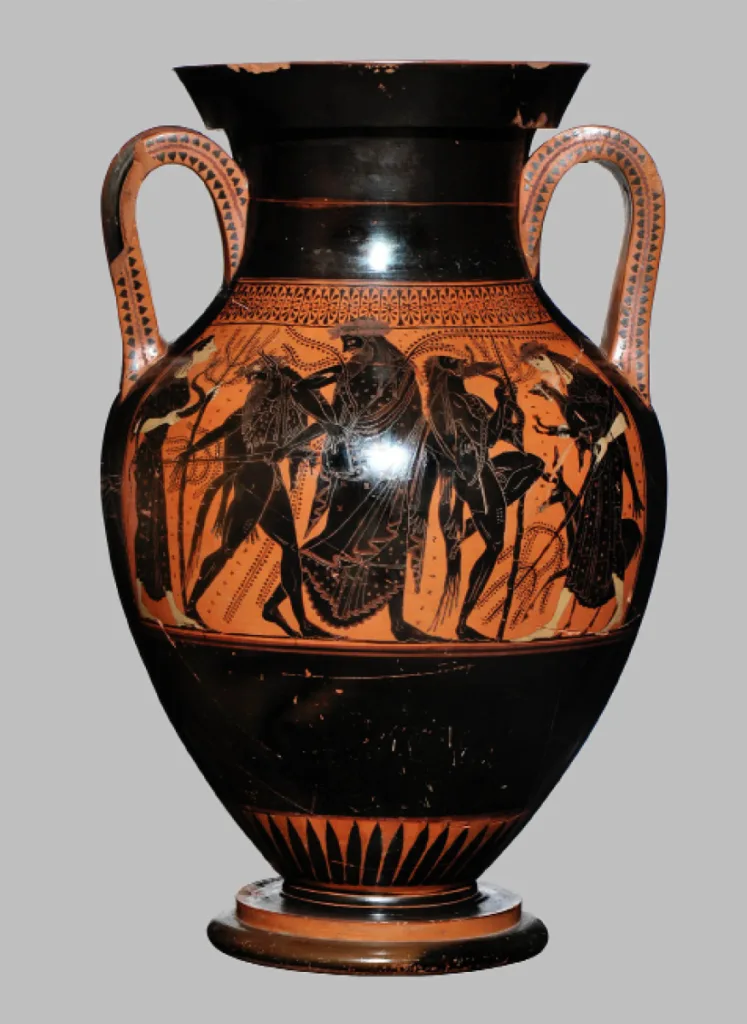

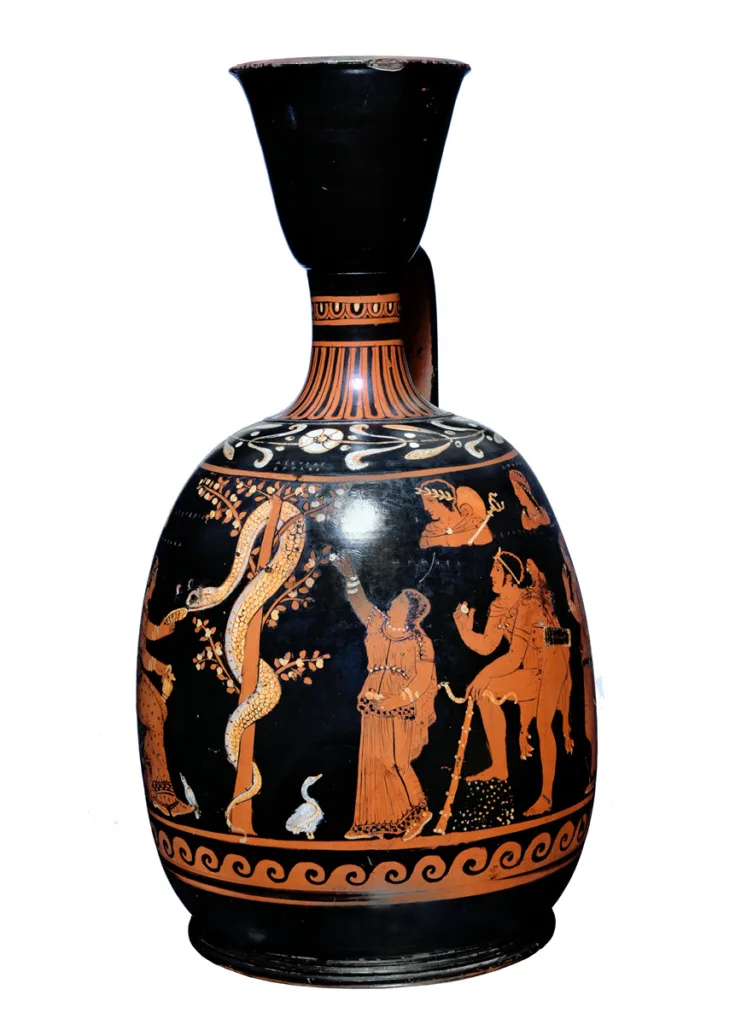

The National Archaeological Museum of Naples holds an extensive collection of artefacts from Magna Graecia. Items such as painted vases, sculptures, tombs, funerary stelae, bronze tools, and domestic objects offer valuable insight into the beliefs, social structures, daily life, and cultural practices of ancient Greek communities in southern Italy.

The museum’s famous Alexander the Great Mosaic, dating to c. 120–100 BCE and discovered in the House of the Faun in Pompeii, depicts Alexander’s battle against Persian King Darius III during the Battle of Issus (333 BCE). The mosaic reflects how Greek history, figures, narratives, and artistic traditions continued to influence Roman culture during the late Republic.

Walking through Naples today—past animated doorways and expressive street life—visitors encounter something that might have felt familiar to ancient Greek settlers: the Mediterranean rhythm of public life. A significant number of Neapolitans express a strong sense of local identity that they consider distinct from broader Italian cultural and linguistic norms, reflecting the city’s unique multilayered historical and regional heritage.

The driver’s declaration, “We have Greek roots, not Roman,” reflects this enduring distinctiveness, a sentiment that seems to be shared by others in the region. It spoke to a truth archaeologists and historians continue to uncover: beneath Naples’ many layers lies the foundation of an ancient Greek past, still felt today.

Next week: We continue with Calabria, a region distinguished by its notable history in Magna Graecia. It was home to prominent Greek colonies such as Sybaris and Croton. Calabria is also known as the site where Pythagoras founded his school and philosophical community. Today, the Griko people of the area maintain a cultural connection to their Hellenic heritage.

*Dr Themistocles Kritikakos is a Greek-Australian historian, philosopher and writer. He holds a PhD in History from the University of Melbourne. His forthcoming book explores intergenerational memories of violence in the late Ottoman Empire, identity, and communal efforts toward genocide recognition, focusing on the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian communities in Australia.

READ MORE: Magna Graecia – Part 1: Hellenism beyond the homeland