The first modern Olympic Games took place in Athens in 1896, thanks to the organizational efforts of one Pierre de Coubertin, a French baron who foresaw the value of a multinational sporting competition. “Olympism is not a system,” Coubertin once said. “It is a state of mind.” Ahead of the Paris 2024 Summer Olympics, smithsonian magazine has presented surprising facts about the famed ancient sporting competition that inspired both Coubertin and later iterations of the Games. Here are five of them.

The Olympic Games weren’t exactly one of a kind.

Olympia wasn’t the only ancient Greek city to host organized athletic competitions. Many communities held their own games, though these varied in prestige. By around 150 B.C.E., about 200 “prize games” regularly took place across Greece, with Athens, Megara, and Boeotia emerging as the most famous venues. The Olympics at Olympia were part of a different class of competitions: the Sacred Games, also known as the Panhellenic Games or the Crown Games.

The Olympic truce is nothing new.

The history of the Olympic truce goes back much further than the 1990s, all the way to the Games’ invention. In the ninth century B.C.E., Iphitos, the ruler of the Greek city of Elis, grew fed up with the region’s never-ending conflicts. Consulting the oracle of Delphi, he was advised to start a peaceful athletic competition. Iphitos and other Greek leaders, including one with whom he was at war, signed a truce known as the Ekecheiria. Contrary to popular belief, this agreement didn’t call for all conflicts in Greece to cease during the Games. Instead, it ensured safe passage for athletes and others traveling to and from Olympia.

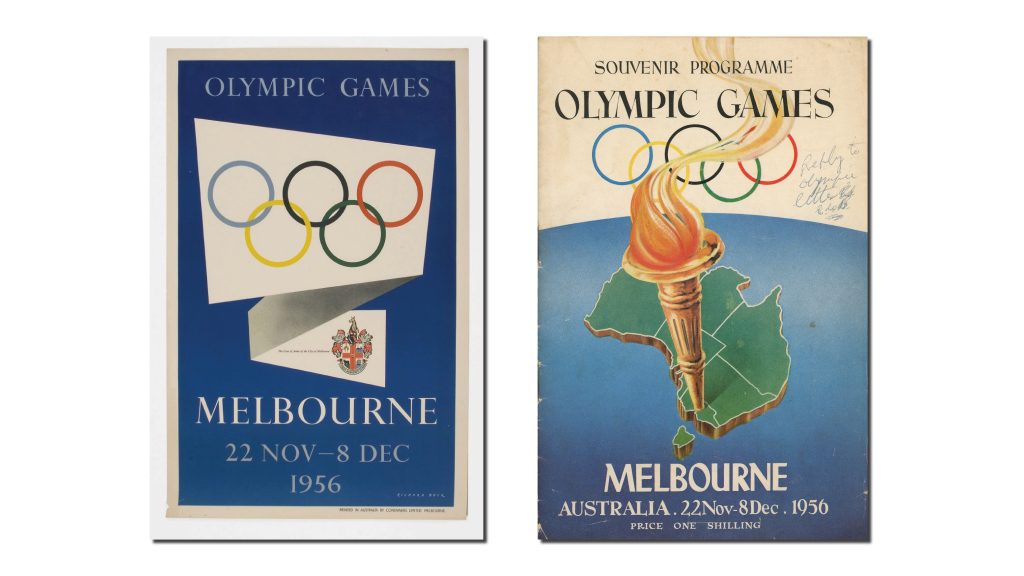

The torch relay wasn’t an ancient Olympic event.

Today, the lighting of the Olympic flame is central to the Games’ opening ceremony. A few months before the Games, a fire is lit in Olympia, and the flame is carried from one location to another, culminating in the lighting of a large torch in the Olympic stadium. However, this tradition began in 1936, when the organizers of the Berlin Games arranged for a flame to be lit in Olympia and transported to Berlin. In ancient times, fire was significant at the Olympics, with a constant blaze maintained at the altar of the goddess Hestia and sacred flames lit at the temples of Zeus and Hera.

Not everyone could compete in the ancient Olympics.

Women were explicitly barred from competing in the Games at Olympia, though they could receive accolades as owners of horses that won chariot races. (The Heraean Games, a separate competition specifically for women, emerged as an alternative to the Olympics but wasn’t part of the official festivities.) Technically, any free Greek male citizen could compete in the Games—the first Olympic victor was reportedly a cook named Coroebus—but they needed to have sufficient time and resources to do so. Olympia required every athlete participating in the competition to train for ten months prior to the Games.

The marathon wasn’t an ancient Olympic event.

The 26.2-mile footrace included in today’s Games—and held frequently worldwide—has been part of the modern Olympics since its revival in 1896, with slightly varied lengths over time. However, no such race existed in ancient Olympia. The longest footrace in the ancient Olympics was the dolichos, which might have been up to three miles. The marathon’s origins are mythical, based on the legend of Pheidippides, an ancient Greek courier who ran 26 miles from Marathon to Athens to announce a military victory over the Persians, then died immediately after delivering the message.

Source: Smithsonian magazine