By Mary Sinanidis.

University of Melbourne Language and Literacy Education Professor Joseph Lo Bianco’s seminar, titled Language in the home: Raising Greek-English bilinguals in Melbourne, was geared towards parents. Only 10 showed up and the other ten members of the audience were a mix of grandparents and teachers. That, in itself, was telling.

The seminar was held at the Greek Centre as part of the Pharos initiative spearheaded by the Modern Greek Teachers Association of Victoria to keep Modern Greek alive.

Pharos means lighthouse, but the ship is sinking fast as parents fail to expose children to the Greek language.

“I told my daughter to come and listen today and even offered to babysit the grandkids but she didn’t want to,” lamented one concerned grandmother.

Professor Lo Bianco said the situation is grim.

“When we look at the statistics there’s a lot to be worried about,” he said. “If we lose the home and we’re struggling in the school and education space, we’re dealing with a rapid rate of attrition.”

Evangelia O’Hehir, who has taught Modern Greek at Northcote High for 38 years, remembered the school’s heyday.

“It was a different demographic 40 years ago, mainly Greek, and we had programs for beginners and advanced and even had an association of Greek parents. Over time, we lost the game because we didn’t create pathways for students who started Year 7 with no knowledge of Greek,” Ms O’Hehir told The Greek Herald, not surprised the current program is at risk.

“Unfortunately, the VCE works for kids with a good basis in Greek and not those starting from scratch so parents choose other languages with pathways that would take them to Year 12, such as French. Pathways are important.”

On a personal level, she is seeing the language disintegrate in her own home with the onus put on her to teach her grandchild Greek.

“I feel uncomfortable. It’s like I’m torturing the child,” she said.

Professor Lo Bianco said one mistake a lot of parents and grandparents make is “teaching” their children rather than “immersing.”

“A trip to Greece!” one mother suggested.

Professor Lo Bianco did not object to a holiday, but even that would be futile, linguistically speaking, unless structured correctly.

Georgia Nikolaidou, Executive Educational Consultant for the Greek Ministry of Education, said her daughter benefitted from being enrolled in a Greek classroom when visiting Greece.

Opportunities like a Greek sports camp surrounded by native speakers could work wonders, the Professor said, adding that a holiday on its own would have little benefit without immersion.

“Teach them soccer in Greek,” he said. “Or just talk about Stefanos Tsitsipas, using Greek.”

It doesn’t need to be a lavish Greek island holiday.

“You are islands of Greek in a sea of English,” he said. “Islands can protect and help but they can also be isolating and isolated.”

Creating networks:

Four Greek mothers present found a way to navigate the choppy and sometimes lonely seas of language learning through friendship. It began when Josephine Pavlou married into a Greek family.

“I grew up speaking only English and I was always very envious of those who could speak another language,” Josephine said, admitting that she is the “pusher” of Greek in her home with such passion that she even got her Greek Australian husband on board to have Greek lessons. They now only speak Greek with the children.

Her language is better than most Greek Australians though she has only been learning for one and a half years, and she attributes this to her teacher, Georgia Lisandropoulou, who – along the way – became her friend.

Having children the same age, Josephine and Georgia formed a bond and took their children to the ELA program where a friendship group formed with Australian-born Demi Pilalis and Elly Ziras.

The women draw inspiration from Josephine and enlightenment through Georgia, while Elly and Demi bring their own insights and experience as Australian-born Greeks who fully understand the challenges their children face.

Demi said, “My Greek is pretty good. I went to Greek school and spent a lot of time travelling to Greece. Both grandparents speak Greek. We have an environment where we could speak Greek to our children, and yet we don’t.”

Elly nods, adding that she grew up with parents who spoke to her in Greek and she responded in English and is now struggling to speak with her children in Greek.

Together, however, the mothers persevere, drawing strength from each other’s journey.

St John’s College teacher Kristian Raspas told The Greek Herald the Greek Orthodox school enjoys success because it offers an environment where Greek language learning is the norm.

“I believe the College is making an effort to show the way to help families not just in academic excellence but also in culture so they can understand their roots,” he said.

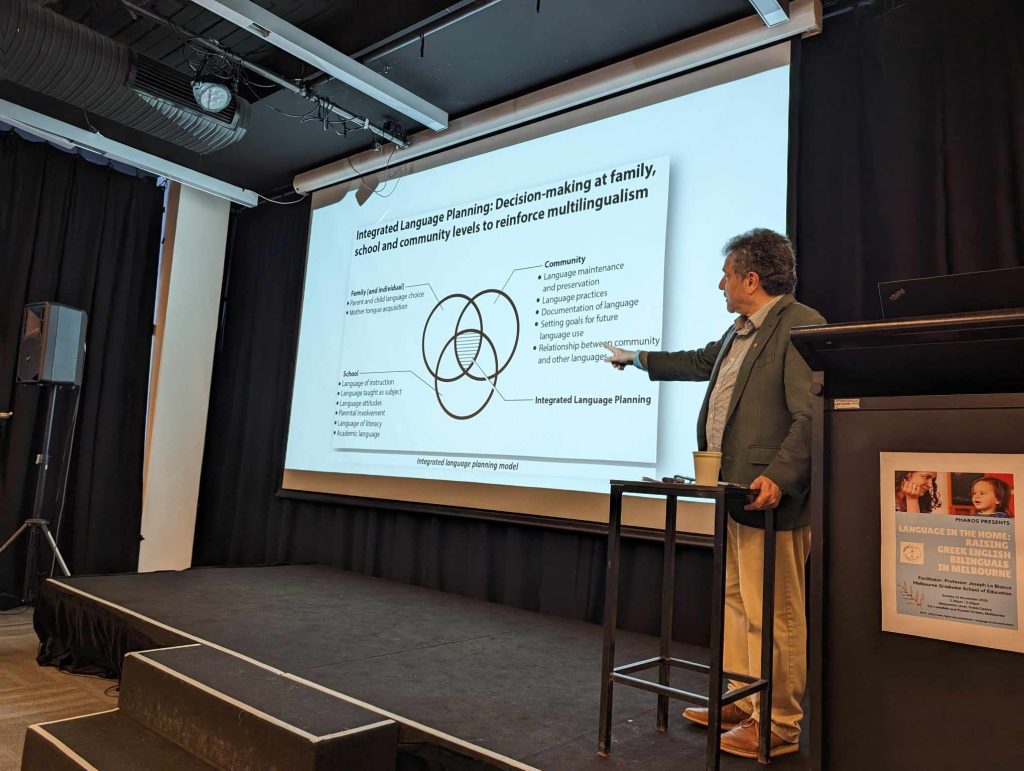

Professor Lo Bianco pointed to a slide with three circles: family, school and community.

“Should the family circle be larger than the other two?” I ask.

“Good question,” he responded, “Let’s think about it.”

The seminar ended with a promise to have a series for parents by Pharos, offering practical tips as to how to keep the Greek language alive in a monolingual country. For more information about Pharos, email mgta.vic@gmail.com.