By George Vardas*

The Feast Day of Saint George (Agios Georgios) was celebrated on Sunday, April 23 by a packed congregation at St George Greek Orthodox Church in the Sydney suburb of Rose Bay.

St George the Martyr is one of the church’s most revered saints who, as a young Tribune in the Roman army, courageously defied the Emperor Diocletian in his persecution of Christians. As the Parish’s Father Gerasimos reminded the faithful, St George “stood up for what is right.”

This celebration coincides with news that the local government authority, Woollahra Council, has recommended that the St George Greek Orthodox Church and War Memorial complex and setting be added to the heritage schedule of the Woollahra Local Environmental Plan 2014 as items of local heritage significance.

This proposed heritage listing has stirred opposition within sections of the parish, including claims that the building itself is an ordinary example of post-war ecclesiastical architecture and does not have any particular historical significance within the wider Greek Australian community.

This opinion piece seeks to explore the reasons for and against the heritage listing of the church.

The heritage of St George Rose Bay:

According to the Church’s own Facebook page, the idea of building a Parish Church in the Eastern Suburbs of Sydney started in early 1956 and was the product of the concerted efforts of some 100 families, many of whom originated from the towns of Akrata and Vatika in mainland Greece and the islands of Kastellorizo and Kythera. Those two islands in particular saw thousands of their sons and daughters migrate to Australia in the early decades of the twentieth century and again in the post-World War II migration wave.

On 20 March 1958, the Greek Orthodox Parish of St Paul Rose Bay was incorporated as a company limited by guarantee. The Memorandum and Articles of Association were prepared by one of the pre-eminent Greek Australian solicitors of the time, Arthur Thomas George (Athanasios Tzortzatos), and the initial subscribers to the newly formed entity comprised some of the leading figures in the local Greek community, including Dr Demetrios Varvaressos, Michael Barbouttis, George Limbers and Arthur George himself.

The new company was charged with promoting the work of the Greek Orthodox Church within the Parish of Rose Bay, commencing with the building of a sacred Church (to be named after St Paul) for the purpose of public worship. The other main object was to erect a war memorial to the Australian soldiers of Greek parents who laid down their lives for Australia as members of the armed forces of the Commonwealth of Australia in the First or Second World Wars and to the Australian soldiers who died in Greece during the Second World War whilst members of the armed forces of the Commonwealth of Australia.

The site at 90-92 Newcastle Street, Rose Bay was purchased on 29 May 1958 and two years later the name was officially changed to the Greek Orthodox Parish of St George Rose Bay.

A year later, Archbishop Ezekiel Tsoukalas, formerly the Bishop of Boston and Chicago and now Primate of the newly created Archdiocese of Australia, took a particular interest in the building of this church and worked closely with the board, which engaged the services of the architectural firm of Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan.

Development approval was finally obtained and on 7 August 1960 the ground-breaking ceremony took place at the site with the blessing of Archbishop Ezekiel. At the celebration of St George’s Day on 23 April 1961, the foundation stone was laid by the Archbishop in the presence of the Governor of NSW, Sir Eric Woodward.

After the church was completed, the first liturgy was conducted on 8 April 1962 with the new Church being consecrated by Archbishop Ezekiel, assisted by Father Miltiades Chryssavgis (who went on to serve as the parish priest until 2009) and Deacon Ezekiel Petritsis.

On 24 November 1962, the Governor of NSW declared the Church a war memorial dedicated to the memory of Australian soldiers of Greek origin who laid down their lives for Australia in the two world wars and to Australian servicemen who died in Greece during World War II.

The Woollahra Council case for heritage listing:

Under NSW Heritage Assessment Guidelines, for an item to be considered to have local heritage significance it needs to meet at least one of seven heritage criteria and at the same time retains the integrity of its key attributes.

“Local heritage significance” in relation to a place, building, work, relic, moveable object or precinct, is defined to mean significance to an area in relation to the historical, scientific, cultural, social, archaeological, architectural, natural or aesthetic value of the item.

Council heritage advisors have concluded that the church meets six of the heritage criteria:

1. As part of the Rose Bay Estate subdivision of the former Point Piper Estate, the St George Greek Orthodox Church and war memorial has local historical significance in its ability to reflect the rapid pattern of development of Rose Bay in the post-World War II era and the growing presence of migrant communities that settled in the area during this time.

2. The Church is significant for its association with migrant communities that settled in NSW following World War II. Since its construction and consecration, the church building has been the focus for worship and the continuity and celebration of Greek customs and traditions in Sydney’s Eastern suburbs.

3. The Church is dedicated as a war memorial and is listed on the NSW War Memorials Register.

4. The St George Greek Orthodox Church was designed by the prominent architectural firm Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan and is considered to be a fine and representative example of that firm’s ecclesiastical buildings. The church building is described as an “interesting example of a Greek Orthodox War Memorial Church, which combines elements of the Byzantine style typically associated with ANZAC memorials with the traditional Greek Orthodox Church style” but incorporating simple and restrained design elements of these styles.

5. It is assumed the St George Greek Orthodox Church is held in high esteem by members of the Parish and the broader Greek Orthodox community of Sydney because, apart from its regular Sunday church services, the building has been a focal point for the local Greek Orthodox community for significant celebrations and events including weddings, baptisms, funerals and religious activities for more than five decades, thereby providing an important part in the community’s sense of place.

6. And finally, the St George Greek Orthodox Church at Rose Bay is rare as one of a very small number of churches of its type, namely, a Greek Orthodox war memorial church (the only other remaining Greek Orthodox war memorial church being St Spyridon at Kingsford)

The planning proposal for the heritage listing of St George was considered by the Council’s Environmental Planning Committee on 6 March 2023 and then by the full Council on 23 March 2023. On both occasions, representatives of the Parish of St George made written and oral submissions and also relied on a heritage report prepared by a town planning and heritage consultancy, Urbis, to dispute the Council’s heritage recommendations.

Opposition to the heritage listing:

Certain members of the Parish Board, together with their heritage consultant, have taken the view there is nothing remarkable about the church.

In terms of historic significance, it is claimed that following World War II there was limited settlement of Greek migrants in the Eastern Suburbs (including Rose Bay) and therefore, the building of the church had no significant connection with the multicultural settlement of Sydney.

It is also claimed that the church has not served as a focal point of cultural, educational and philanthropic life in the Greek community. Even the church’s dedication as an ANZAC Memorial is relegated to an “unsubstantiated, incidental connection with Australia’s military history” with no ongoing connection with the ANZAC legacy.

As to the church’s aesthetic or technical significance, it is claimed that St George Rose Bay cannot be identified as a true church in the Byzantine style because of the lack of a traditional dome which one would associate with Greek Orthodox basilicas, as well as its alleged failure to convey the sense of grandeur and otherworldliness expressed through decorative ecclesiastical elements such as frescoes and ornate chandeliers. According to Urbis, it is just a “simple place of worship” designed by a firm of architects who were not highly significant or prominent.

As to whether the church has a strong or special association with the local community, Urbis concedes that in addition to regular Sunday church services, the building has been a focal point for the local Greek Orthodox community for significant celebrations and events including weddings, baptisms, funerals and religious activities for more than five decades providing an important part in the community’s sense of place. However, the connection is not with the bricks and mortar – the fabric of the building – but with the movable icons and other religious artefacts within the building and a general sense of belonging. Accordingly, it recommends that the social significance of the place be further investigated in order to reach a definitive conclusion prior to the heritage listing of the building.

In terms of rarity, the building is dismissed as a “pedestrian example” of a Greek Orthodox Church and is not rare because there are more than thirty Greek Orthodox churches in Metropolitan Sydney.

And finally, as to whether St George Rose Bay is an important representative item of a cultural place, again the analysis is scathing. The church is declared to be a poor example of its type as it was not designed with a great deal of regard for the typical Byzantine language of Greek Orthodox churches. The stone plaque for those ANZACS and Greeks who have fallen in the two wars is described as an “intangible memorialising of these fallen soldiers.”

In short, the church fails to satisfy almost every heritage criterion and therefore, does not reach the threshold of local heritage significance.

The Parish President also claimed that the Orthodox faith meant if the church was to be relocated or closed down, it would be necessary for the existing church building to be demolished and as such a heritage listing would be “offensive” and against the faith.

What is the heritage significance of St George Greek Orthodox Church Rose Bay?

As a writer and freelance heritage consultant of Greek Australian background, and having attended St George at Rose Bay on numerous occasions over the years for weddings, funerals and liturgies (as recently as 23 April), I must respectfully disagree with those who oppose the proposed heritage listing.

For a start, in hagiographical terms, St George the Great Martyr is one of the most venerated saints in the Greek Orthodox Church. He is more than just a “military saint” as the Urbis report describes him.

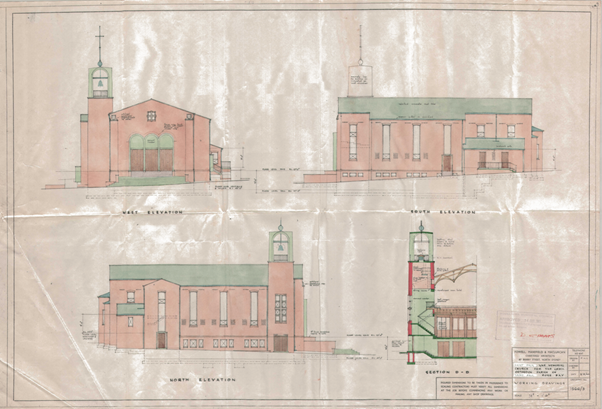

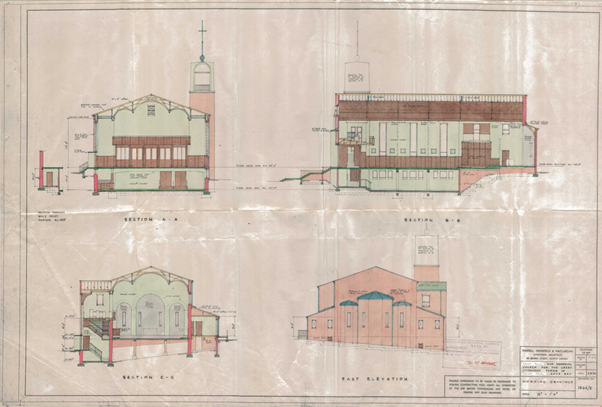

In architectural terms, despite the claim by Urbis that the original architectural plans for the church cannot be located, I was able to obtain from Woollahra Council copies of the working drawings by the architectural firm of Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan. Those plans were also incorporated in the heritage advice provided to the Council Environmental Planning Committee.

Indeed, on its own Facebook page, on the occasion of the 60th anniversary of the official opening of the church, the St George Rose Bay Parish published an image of the front and side elevations of the church together with the architects’ impression of the iconostasis.

Significantly, Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan are described as “highly reputable and experienced” and that they received guidance from the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese and the Board President, Dr Dimitris Varvaressos, in incorporating Orthodox features into the church building.

This opinion is actually confirmed by one of the leading textbooks on Australian architecture – Richard Apperley et al, Identifying Australian Architecture Styles and Terms from 1788 to the Present Hardcover (1994) – which refers to Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan as “key practitioners” in post war ecclesiastical architecture (1940-1960).

The other examples of the work of Fowell, Mansfield & Maclurcan, which are cited with approval in the Parish’s social media post, are St Augustine’s Catholic Church in Yass which was opened in 1956 and which is said to bear a resemblance to St George.

The HMAS Watson Bay chapel, also dedicated to St George the Martyr, was completed in 1961 and is a memorial to all those who lost their lives in all wars.

And, finally, St Anne’s Church in North Bondi was awarded the Sir John Sulman Medal by the Royal Australian Institute of Architects in 1935. In his history of the Sulman Medal, Andrew Metcalfe described the church as “a tour de force of brickwork construction with highlights of sandstone trim” and being “perhaps the highlight of ecclesiastical architecture in interwar Sydney.”

Praise for the “sacred edifice” of St George Greek Orthodox Church:

According to the Parish’s own website, St George Rose Bay is now a community of over 2000 Orthodox Christians in the eastern suburbs of Sydney.

On 4 May 2022, just over 60 years after the first liturgy, Father Miltiades Chryssavgis returned to the church that he so faithfully served for almost five decades and surveyed the rich history of the parish, noting:

“Our primary duty today during this celebration is to remember with gratitude the invaluable services of the pioneers and their great sacrifices to build this magnificent sacred edifice for the spiritual, liturgical and pastoral needs of the Greek Orthodox faithful who lived in the area.”

In November 2022, the Church celebrated its 60th anniversary with a lavish black-tie ball in Sydney attended by Her Excellency The Honourable Margaret Beazley AC QC, Governor of New South Wales, the Consul General of Greece in Sydney, Ioannis Mallikourtis, and Archbishop Makarios, the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church of Australia.

Archbishop Makarios lauded the parishioners and benefactors of the church and declared that he was in no doubt that Agios Georgios is well-pleased with the Parish’s noble endeavours “as you bring God’s light to this corner of Sydney.”

The NSW Governor was equally effusive in her praise of the “legendary” St George Rose Bay and added:

“When I was thinking about you as a parish, your church as a place in our community, it did seem to me that three things were of particular importance. The first is community – that’s your heart. It is your devotion at your church and as part of that community which binds you. Also at the heart of this parish of St George is commemoration because it is a church which has been dedicated to service people, to Greeks, Greek Australians who have served in the Australian Defence Services… that is an extraordinary dedication.”

Even in the ball program that was printed for the occasion, the Parish President, Spero Raissis, praised the community’s Orthodox faith which he correctly described as a “unifying element in the Greek migrant community” and which, as he noted, had led to the creation of the “wonderful St George Church building”.

Greek Orthodox Architecture – to Byzantium and beyond:

Although the Greek Orthodox Church is steeped in Byzantium tradition, the fact that a particular church does not strictly imitate Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture or opulent decoration does not diminish its standing as a religious building.

In Australia, and certainly from the 1960s, church committees and their architects increasingly recognised the need to adapt ecclesiastical architecture to contemporary society both in terms of materiality and scale. Minimalist or modest designs that were sensitive to their residential surroundings were not uncommon.

In the case of St George Rose Bay, it is apparent that the Parish Board in the late 1950s worked with the church hierarchy and the architect to deliver a design that would foster a sense of community. In architectural terms, this did not necessarily mean a slavish copy of traditional Byzantine cathedrals in Greece but an adaptation of both traditional ecclesiastical elements and post-war modern religious design to reflect the emerging Greek immigrant identity in their new adopted homeland in Sydney. The resulting architectural edifice did not necessarily have to incorporate everything, everywhere and all at once, in terms of traditional basilica domes, ornate wall frescoes, large chandeliers or lavish gates of the iconostasis.

In Apperley’s discussion of late 20th century immigrants’ nostalgic style, an example is given of the Greek Orthodox Church of the Prophet Ilias in Norwood South Australia which was built in 1975 and in which “traditional Greek church forms are handsomely simplified.” In particular, the author notes the traditional west front derived from Romanesque architecture, the bell tower with open top cupola and the traditional triple-arch entry.

St George Rose Bay employs traditional Greek Orthodox elements which are also handsomely simplified.

As the Urbis report concedes, it is a modern building based on traditional form consisting of blond face brick, concrete detailing and an entry triptych of three large concrete classical arches painted white over the large panelled timber front entrance doors. It features a brick campanile bell tower with rendered open cupola and free-standing cross atop the cupola. Internally, the church ceiling is a triple-vaulted timber board ceiling. The iconography and other liturgical elements are certainly not understated.

The interior of the church also incorporates a blend of traditional Greek architecture, Byzantine influences and the spiritual symbolism of the Orthodox faith in terms of iconography and distinctly Orthodox decorations but not in an overstated way.

I therefore challenge the claim that St George at Rose Bay is “modest and austere” and is not readily recognisable as a Greek Orthodox Church, particularly as the eastern orthodox architectural landscape in Sydney is very diverse to say the least.

The first Greek Orthodox Church in Sydney, Agia Triada (Holy Trinity) Church in Redfern was opened in 1898. Originally built in the Byzantine style of architecture, in 1931, the facade of the now heritage listed church was replaced with a two-storey Inter-War Romanesque construction of face brick with rendered dressings, buttresses and a gable roof. As a result of these alterations, the entrance to the church is now framed by two brick towers and is headed by an arched leadlight window above a triple arched entranceway.

The second church in Sydney, the Cathedral of Saint Sophia (Holy Wisdom) in Paddington, was designed by a famous architect, Walter Leslie, and is announced by fluted Iconic columns which support a massive dentilated entablature with a broad pediment reflecting a neo-Greek Revival architectural style (Ionic Classical exterior with a Byzantine influenced interior).

Since the 1970s the Greek Orthodox Church has also occupied churches built in Victorian Gothic or Gothic revival style, including notably the Cathedral of the Annunciation of Our Lady at Central (formerly St Pauls Anglican Church), Saint Nectarios Burwood and Saint Sophia & Three Daughters Surry Hills.

The Saints Constantine & Helen Greek Orthodox Church, Newtown was built in the Victorian academic style in the mid-19th century and formerly operated as the Uniting Church before being acquired in 1970.

The spiritual significance of these Greek Orthodox churches has not been diminished by their ‘un-Byzantine’ appearance.

And finally, as to the claim that any future deconsecrating of the church would mean demolition under canon law, I note that the former Saints Constantine & Helen Greek Orthodox Church in Chicago, a church completed in 1952 and built in traditional Byzantine style, was deconsecrated in 1972 and sold to the Nation of Islam. It is now the Mosque Maryam.

The Greek-ANZAC connection: more than just a commemorative plaque?

The Urbis report contends that the decision to dedicate the church as an ANZAC Memorial was almost an afterthought, betraying an incidental connection with Australia’s military history, and is no longer significant (if it ever was). I respectfully disagree.

When the Parish was established in 1958 as the Greek Orthodox Parish of St Paul (later changed to St George), its constitution enshrined a specific commitment to honour the ANZAC traditions that were forged between Greece and Australia during two world wars.

It is significant that St Spyridon Greek Orthodox War Memorial Church in Kingsford, which was built during the 1970s in a simplified East Mediterranean style, has been heritage listed and it is noted that like St George Rose Bay, St Spyridon is a Greek Orthodox church building that was designed specifically to commemorate Australian and Greek soldiers who fought in World War I and World War II.

The ANZAC tradition at St George Rose Bay therefore runs much deeper than a mere plaque on the wall.

Heritage now:

Woollahra Council has deferred the matter to enable further investigation of the heritage and social significance of the church and whether it is appropriate for heritage listing. It will also investigate whether there is an active development application for the site on the corner of Old South Head Road and Newcastle Street, Rose Bay and also whether further legal advice is required.

When all is said and done, heritage is about celebrating and preserving places that have meaning and significance for us.

The St George Greek Orthodox Church at Rose Bay is a vibrant part of the Greek Australian community and underlines our common Greek migrant heritage. It continues to provide a sense of place that is worth preserving.

It also stands for what is right.

*George Vardas is a former President of the Kytherian Association of Australia and freelance cultural heritage consultant.