By George Vardas I Secretary, Australian Hellenic Council NSW I Member, Acropolis Research Group

“Owing to its historical significance, the conversion of the Hagia Sophia Mosque in Istanbul – a unique architectural monument – into a museum will gratify the entire Eastern World and will cause humanity to gain a new institution of knowledge” – Turkish Council of Ministers, 24 November 1934.

The imposing Church of Hagia Sophia (Greek for Holy Wisdom) in Istanbul (formerly Constantinople) is an incredible monument that has anchored Byzantine and Ottoman empires over the ages without ever losing its original Christian aura. Since 1935 it has operated as a museum for the world where its architectural splendour and ornamental treasures could be admired by all.

That all came to an abrupt halt with the recent decision of the Council of State – Turkey’s highest court – to re-convert Hagia Sophia into a mosque to satisfy the neo-Ottoman irredentist fantasies of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Turkey’s hardline President

In this article I seek to review the history behind the original conversion of Hagia Sophia into a museum and the Turkish Government’s oft-repeated claims of its commitment to preserving the heritage of the historic sites of Istanbul both at home and internationally. I conclude that this is nothing more than a crude, symbolic gesture aimed at Erdogan’s conservative Islamist base and does nothing to enhance Turkey’s reputation in protecting monuments, buildings and other landmarks of world cultural heritage significance.

Atatürk and the musealisation of Hagia Sophia as a “new institution of knowledge”:

The self-styled Founder of Modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Pasha (later known as Atatürk), wanted to cut the last of the vestiges of the country’s imperial and Islamic past when he founded the new republic as a secular society. One of the first acts of the new Republic was the opening of the Topkapı Palace, which had been the imperial seat of Ottoman sultans for centuries, as a museum.

It was also around this time that there was renewed interest in the hidden mosaics and other treasures of what the Turks knew as AyaSofya. Although the Hagia Sophia remained a functioning mosque International interest in this Byzantine marvel continued in the early years of the Republic.

The debate as to its future began in earnest after Thomas Whittemore, the head of the Byzantine Institute of America, was granted permission in 1931 to undertake a restoration and conservation project at Hagia Sophia including the uncovering and restoration of the mosaics of Hagia Sophia. This work and the revealed mosaics increased awareness about the historical significance of the building.

Whittemore was later to write of his dealings with Atatürk who took an active interest in the restoration works: “Santa Sophia was a mosque the day that I talked to him. The next morning, when I went to the mosque, there was a sign on the door written in Atatürk’s own hand. It said: ‘The museum is closed for repairs’”

On 25 August 1934, the Turkish Minister of Education, Abidin Özmen, wrote to the Director of the Museums of Antiquities in Istanbul directing him to start putting in place arrangements to convert the mosque into a museum.

According to the recollection of Özmen as reported in the Hagia Sophia visitor’s book, Atatürk explained his intention to convert Hagia Sophia into a museum with the following words:

“It will be reasonable to convert it [Hagia Sophia] into a museum, which will be open to the visits of all nations and religions rather than letting it belong to a single religion and a single group, and it will particularly be appropriate to collect the Byzantine works in this new museum.”

On 24 November 1934 the Turkish Council of Ministers finally passed a decree, declaring:

“Owing to its historical significance, the conversion of the Hagia Sophia Mosque in Istanbul – a unique architectural monument – into a museum will gratify the entire Eastern World and will cause humanity to gain a new institution of knowledge.”

Hagia Sophia opened its doors in 1935 as a museum which illuminated an equal stance towards all cultures and religions. It no longer represented the superiority of Christianity over Islam or Islam over Christianity. It was a symbol of universal tolerance and understanding of the great cultures that had passed through its great doors over the centuries.

UNESCO World Heritage List and the Historic Areas of Istanbul:

For years Turkey was keen to get the city of Istanbul on the World Heritage List, particularly given the threat of pollution arising from industrialisation and rapid and initially uncontrolled urbanisation that was jeopardising the historical and cultural heritage of the old town Finally, with the ratification of the World Heritage Convention by Turkey in 1983, the nomination of the historic areas of Istanbul could be considered.

In 1985 the Historic Areas of Istanbul was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List under several distinct cultural criteria for outstanding universal value.

As the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) noted at the time, one could not conceive of the World Heritage List without this city which was built at the crossroads of two continents, which was successively the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire the Byzantine Empire and the Ottoman Empire and which has constantly been associated with major events in political history, religious history and art history in Europe and Asia for nearly twenty centuries

The four historic areas of Istanbul are the Sultanahmet Archaeological Park which features Hagia Sophia, Hagia Eirini, the Hippodrome, Topkapı Palace and the Sultanahmet Mosque (also known as the Blue Mosque); the Süleymaniye Conservation Area (the aqueduct of Valens); the Zeyrek Conservation Area (centred on the Pantocrator Church now Zeyrek Mosque) and the Land Walls Conservation Area.

But without any doubt the historic and spiritual core of the city is and has always been the Byzantine Church of Hagia Sophia.

In assessing the Outstanding Universal Value of the Historic Areas of Istanbul, there were four relevant criteria.

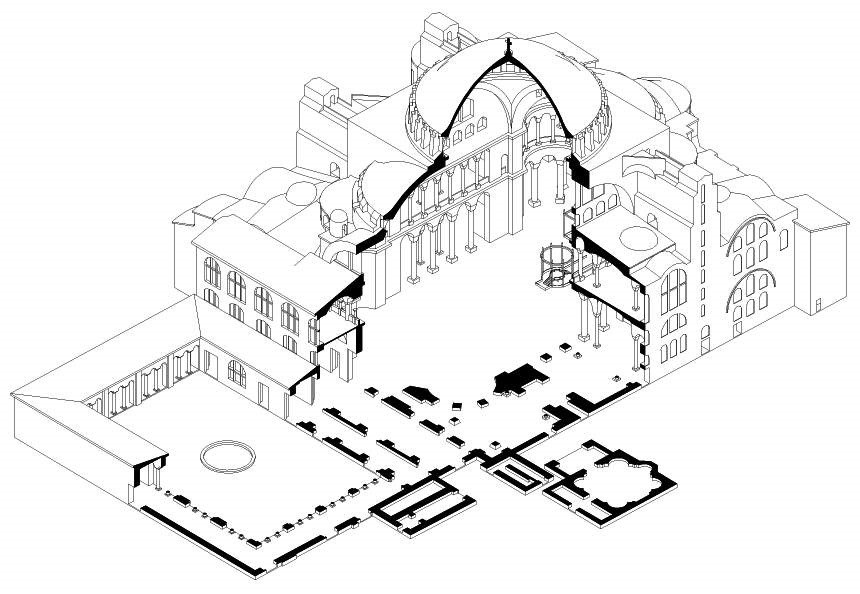

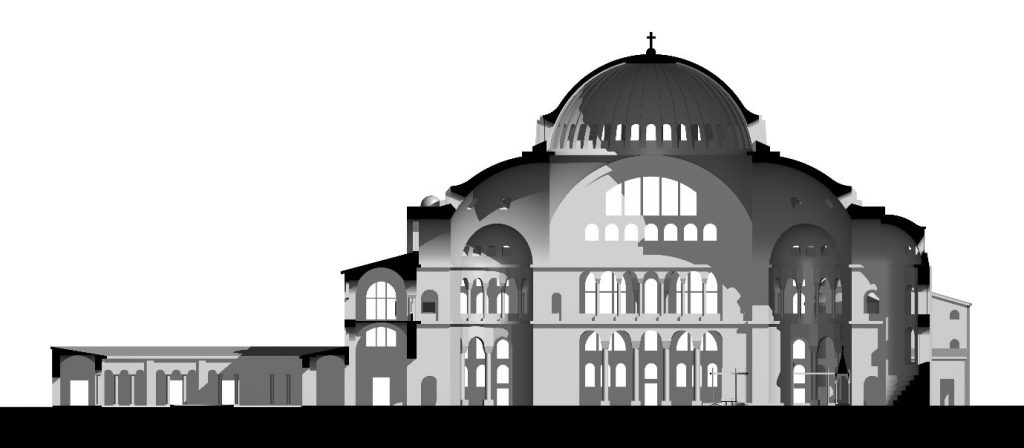

Under Criterion 1 the city represents a masterpiece of human creative genius which it clearly does through unique monuments and masterpieces of universal architecture, most notably the Church of Hagia Sophia which was built by Anthemios of Tralles and Isidoros of Milet in 532-537 and the 16th century Süleymaniye Mosque, a masterpiece of architecture by the Ottoman (with Greek/Armenian origins) architect, Koca Sinan.

Secondly, throughout history, the monuments in the city’s centre have exerted considerable influence on the development of architecture, monumental arts and the organization of space, both in Europe and in Asia. Thus, the long terrestrial wall of Theodosius II with its second line of defences, created in 447, set a benchmark for military architecture even before Hagia Sophia became a model for churches and later mosques. Within the zone of the ramparts there is also the old church (now museum) of the Holy Saviour in Chora (presently Kahriye Carnii) with its incredible mosaics and paintings from the 14th and 15th centuries.

Thirdly, the city of Istanbul bears a unique testimony to the Byzantine and Ottoman civilisations.

And under the fourth criterion, buildings such as Hagia Sophia are an outstanding example of a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which illustrates significant stages in human history.

In 2000 in a report on Hagia Sophia a UNESCO team comprising archaeologists, engineers, restorers and other specialists noted that Hagia Sophia is “one of the very few most important monuments in the world”.

Cultural co-operation between Greece and Turkey:

On 4 February 2000 an agreement was signed between the Hellenic Republic and the Republic of Turkey on cultural co-operation. Article 3 relevantly provided that the parties shall promote their active and friendly co-operation and mutual assistance in the fields of cultures of culture, science and education within UNESCO and the Council of Europe and other international organisations and they shall “refrain from actions which are likely to be opposed to the other party’s interests”.

“Let’s make Istanbul a museum city”:

On 21 March, 2005 the then Turkish Culture and Tourism Ministry Undersecretary Mustafa Isen resolved to transform the Sultanahmet surroundings into a museum city.

Just over a year late on 22 June 2016 Prime Minister Erdoğan (as he then was) while speaking at the opening of the restored Bogazici University Kandilli Observatory and Earthquake Research Institute Museum, said that Istanbul, which dazzles with its historical and cultural elements, had added a new museum which carries the past to the present and which will revive the consciousness of the people. He declared: “Let’s make Istanbul a museum city.”

The Alliance of Civilizations Initiative:

The Alliance of Civilizations (AOC) was launched in 2005 jointly by Turkey and Spain and subsequently became a UN initiative upon its endorsement by the Secretary-General of the United Nations.

According to the AOC charter preamble, various extremist elements were said to exploit the mutual suspicion, fear and polarisation between the Muslim countries and Western societies. The Alliance’s aim is to overcome this tendency by enhancing mutual respect between cultures bearing in mind that only a comprehensive coalition can prevent the deterioration of this situation, which threatens international peace and stability. The Initiative is based on the idea that all societies are interdependent on the matters of development, security, environment and welfare. It aims at establishing a common political will in order to overcome prejudice, misperception and polarisation.

Fifteen years later, Erdoğan has jettisoned any pretence to upholding these principles in his quest for a neo-Ottoman caliphate and the abrupt Islamisation of a beacon of Christian and Ottoman civilisation. Turkey’s actions in relation to Hagia Sophia have undermined the very spirit of the AOC and run contrary to any sense of dialogue and cooperation.

Skyflight of fantasy:

Readers of the August 2013 issue Skyflight, the in-flight magazine of the State-owned Turkish Airlines, were treated to a confronting cover: “Ayasoya: Sultanlarin Camii: Hagia Sophia: Mosque of Sultans”.

The article read almost like a brief for the caliphal prosecution as it ventured into the alleged legal irregularities surrounding the decision taken by Atatürk and his Council of Ministers in 1934 to convert Hagia Sophia into a museum., claiming that there are doubts regarding the legitimacy of that decree insofar as cadastral records show the property as the “Grand Imperial Hagia Sophia Mosque Complex consisting of a Mausoleum, an a Clock room, a Madrasa and Leased Property” belonging to the Fatih Sultan Mehmed Foundation, according to a title deed dated February 19, 1936.

Fast forward seven years later. After Erdoğan published his presidential degree apologists for the Turkish regime asserted that Hagia Sophia is a part of that Foundation as a “mosque” and is therefore legally a property of this endowment and according to the Turkish Law on Endowments, a property should primarily be used in pursuant of function it was written in its founding document .

But even in Turkish Islamic culture the Hagia Sophia is laden with significance far beyond that of simply being a mosque.

2015 celebration of 30 years on UNESCO World Heritage List:

Despite this, Turkey has outwardly accepted plaudits for the inclusion of the Historic Areas of Istanbul on the World Heritage List. In April 2015 the Mayor of Istanbul, Kadir Topbaş (also an architect) attended a ceremony where the Director-General of UNESCO, Irina Bokova, congratulated the city and recalled that “the universal outstanding value of Istanbul resides in its unique integration of architectural masterpieces that reflect the crossroads of European and Asian cultures over many centuries”. Ms Bokova added:

“Istanbul is emblematic for many civilizations. It sends a strong message to the world, in particular at this troubling period when we are witnessing the destruction of invaluable cultural heritage, ranging from temples, to mosques and churches in many parts of the world,” declared Irina Bokova.

In response, Mayor Topbaş expressed his appreciation for the “excellent cooperation between Turkey and UNESCO” and emphasised that “culture brings people together and should be put forth as a common language of humanity everywhere in the world”. In conclusion, he underscored the need to “preserve not only the buildings but also the lifestyles that the buildings house through a multidimensional approach.”

Istanbul declaration on the protection of world heritage:

On 11 July 2016 the 40th session of the World Heritage Committee was held in Istanbul (rather ironic in view of recent developments). The State parties (including Turkey) acknowledged the paramount importance of cultural and natural heritage for people’s values, identities and memory and resolved to harness cultural heritage as a force for dialogue and mutual understanding in order to foster a sense of common history and the intellectual and moral solidarity of humanity, as the lasting foundation for peace. More tellingly, the World Heritage Committee reminded all States Parties of their obligation to safeguard cultural and natural heritage of Outstanding Universal Value at national and international levels and to take all appropriate legislative measures in that direction where necessary.

Except when it comes to Hagia Sophia which is at the core of a UNESCO world heritage site and which together with its surviving iconography (mosaics and frescoes from the medieval Byzantine period) bear witness to a grandeur of Byzantine art and architecture that has not diminished.

The Other Hagia Sophia in Trabzon (Trebizond):

After the capture of Constantinople during the Fourth Crusade in 1204, the Empire of Trebizond was

founded as a successor state of the Byzantine Empire with Trabzon as its capital. The church dedicated to Hagia Sophia was built during the reign of Manuel I Komnenos in the thirteenth century as a monastic and funerary church, replete with magnificent Byzantine mosaics and iconography from the 13th century.

In recent years this Byzantine church has also been converted into a mosque even though conservation masterplan of Trabzon in force still identified the monument and its vicinity as a “museum development site”. A ceiling and rudimentary screens have been inserted so that the whole upper part of the building’s central space, including the arches, vaults, domes, mosaics and frescoes, have all been obscured with red carpet unfurled over the marble floor.

Does a similar disastrous fate eventually await Hagia Sophia in Istanbul?

Universal condemnation of the re-conversion of Hagia Sophia as a museum:

The hue and outcry have been predictable in scientific and academic circles but worryingly less so amongst politicians and diplomats

UNESCO lamented the lack of dialogue on the part of Turkey and reminded Erdoğan that States, including Turkey, have an obligation to ensure that any proposed modifications do not affect the Outstanding Universal Value of inscribed sites on their territories and that in the case of Hagia Sophia the artistic works representing all the cultural layers of this incredible monument will continue to be accessible side by side.

ICOMOS was more to the point:

“Since 1934, Hagia Sophia has been a museum, a decision motivated as a symbolic gesture to openly present to the public the spectacular multilayered cultural richness of this monument. The Turkish people and tourists from all over the world have since then had the opportunity to visit this architectural masterpiece and contemplate its stunning works of art of the Byzantine and Ottoman periods, an intercultural exchange inscribed in the museum’s DNA.”

David Gardner in the Financial Times took aim at the neo-Ottoman fetishes of the Turkish President and did not hold back:

“As the choreography of culture wars goes, it cannot be faulted. Recep Tayyip Erdogan, the Turkish president, last week decreed that the 1,500-year-old Hagia Sophia, the Byzantine cathedral-turned-mosque-turned-museum, will once again become a mosque. This crown jewel of Istanbul’s majestic skyline is being weaponised for the purpose of mass distraction. Mr Erdogan, the towering figure of Turkey this century, has won more than a dozen electoral victories to sweep aside a parliamentary system with an authoritarian presidency that allows him to rule like a neo-Sultan.”

The renown Byzantine scholar, Judith Herrin, was equally dismayed at Erdogan’s brutal ethnc and cultural cleansing:

“By serving as a museum, Hagia Sophia, a vast, 1,500-year-old structure that previously served as a church and then a mosque, represented the essence of Istanbul, a place where world-changing empires and religions conflicted and intersected but whose monuments and artefacts can be enjoyed by all. (The Turkish Court) ruling marks a symbolic end to this legacy of tolerance.”

Political leaders have been much more circumspect. The US President Donald Trump who appears to have a very ‘cosy’ relationship with Erdoğan has said nothing. His Secretary of State, Mike Pompeo, expressed “disappointment”. British Prime Minister Boris Johnson responded that it was within Turkey’s “sovereign rights” to take these steps as though the world heritage significance of the monument counts for nothing. Australia, which is still beholden to a flawed Gallipoli mythology and does not want to upset the Turks, has been silent.

Hagia Sophia belongs to the world:

Since 1934 Hagia Sophia operated as a museum to present to the public the spectacular multilayered cultural richness of the monument and the many layers of history it embodies. In truth, Hagia Sophia does not belong to any one religion or nation but to all humanity.

It is arguably the most celebrated and most recognisable component of the UNESCO-listed Historic Areas of Istanbul. Converting it to a mosque effectively deletes ninety years of history as a museum and as a model of religious freedom in harmony with the ecumenical status of the building.

President Erdoğan is currently mired in external wars in Syria and Libya and yet is deliberately provoking Greece over territorial rights in the Eastern Mediterranean and forced migrant refugee flows across the Turkish border. The Turkish economy is stagnant, especially in the wake of the Covid-19 epidemic crisis, and like any authoritarian despot under pressure, Erdoğan looks to other distractions to consolidate his far-right Islamist base and to feed his neo-Ottoman dreams of a new, greater Turkey that sheds its modern secular robes and embraces an aggressive brand of Islam that threatens the region.

The re-conversion of Hagia Sophia to a mosque was an easy target to achieve with a stacked judiciary and has become a symbolic act that feeds to Erdoğan’s nationalist-populist base.

Despite claims that Istanbul is a museum city and that Turkey is a faithful State actor in UNESCO and on the world cultural heritage stage, the brutal truth has been exposed by this decision. Turkey under Erdoğan simply does not respect religious and cultural diversity throughout the world.

But Hagia Sophia will long outlive this indignity, given its world heritage status and iconic recognition as the most important surviving Byzantine structure and one of the world’s great monuments. As Bissera Pentcheva, Professor of Classics at Stanford University, has observed every element of this famed Byzantine monument was designed to invoke a sense of the divine.

No misconceived or politically motivated temporal intervention will ever change that.