By Marina Siskos

- From the ultimatum to the post-war world era. A chronological purview

| October 28, 1940: In the remote Albanian territory, the Greeks repel the Italian invasion. |

| April 1941: German Wehrmacht braces its defeated and humiliated Italian ally. |

| April 1941: Germany’s invasion of Greece from the north. |

| September 1942: The Allies lift the Naval blockade. |

| November 1942: The blowup of the Gorgopotamos rail viaduct. |

| June 1942: The Distomo massacre by the Nazis. |

| October 1944: The government in exile (Cairo) returned to Greece in mid-October, accompanied by British troops. |

| End of 1944: Northern Greece was liberated by the allied forces. |

| July 1944: The Bretton Woods conference signified the coming into being of a new, post-war world system. |

| October 1944: The Tolstoy conference in Moscow takes place, whereby the “spheres of influence”, have been curved between Winston Churchill and Joseph Stalin. |

| October 1944: The Germans evacuate Athens. |

| December 1944: A civil war between EAM and the government forces (national guard) broke out in the capital. |

| February, 1945: The Varkiza agreement promises a regime of free expression, amnesty for political crimes, a purge of collaborators and a plebiscite and election to conducted in complete freedom. In return, the armed forces of resistance were asked to be demobilised and in particular ELAS, both regular and reserve. |

| March 1947: The declaration of the Truman doctrine. |

| June 1947: Secretary of State, George Marshall, announced the government’s decision to help the financial reconstruction of Europe. |

| September 1947: A new coalition government of the populist and liberal parties was formed under the premiership of the moderate Themistoklis Sofoulis. |

| July 1949: Joseph Tito closes the Yugoslavian border, denying the Democratic Army of Greece (DSE) shelter. |

| October 1949: Ceasefire is signed. |

2. State of war: A shadow of the former country

The Axis occupation produced swift and thorough changes in Greek life (Fritz, 1996: 583). The vicious cycle of economic exploitation and racialist policies of the new order in Europe, was exacerbated by bitter rivalry between Italian and German administrative authorities (ibid). The results were pernicious: a sudden drop in economic production was followed by a sharp rise in unemployment: disruptions in the harvesting and food distribution, lead to a catastrophic famine; also, a steady rise in prices, producing hoarding and open black marketeering; loss of respect for and collapse of the state’s authority; the destruction of the traditional family unit, as women and teenagers claimed a newly assertive role; and the progressive radicalisation of large segments of the Greek state (ibid). The latter included large segments of the prewar middle classes (ibid).

a. The war frontiers

Gradually and radically, the Greek state was led to its eventual disintegration, after divide and conquer was imposed. On April 9, 1941, Thessaloniki became the first city to be seized by Wehrmacht forces (Chandrinos, Droumpouki, 2018: 17). Italy became entitled to take the lion’s share of the spoils: the Bulgarians received Thrace and eastern Macedonia, whereas the Germans retained a few, key positions; Piraeus, central Macedonia with Thessaloniki, and some strategically important islands, including the greater part of Crete (ibid). German troops reached Athens on 27 April 1941 (Peponas, 2021: 83). The zones of the occupations were decided:

Bulgarians were awarded a strip of territory in the north-east, part of Macedonia and much of Thrace (Martin, Mel, 2012). East of the Bulgarian sector, there was a small strip along the border with Turkey, which remained under German control (Martin, Mel, 2012: 2). The main block of German-occupied land lay in the center of northern Greece, around the city of Thessaloniki and the Germans were also responsible for Athens and a small area around it, for several islands in the Aegean Sea and for most of Crete (Martin, Mel, 2012:2). The Italians became responsible for the bulk of mainland Greece until the surrender of the Italian forces in September 1943 (Martin, Mel, 2012: 2).

Daily life in the cities was becoming dehumanising, as “it has been the first time in modern history that cities, even of metropolitan dimensions, came at the spotlight of military operations” (Chandrinos, 2022: 466). The conflict between the Axies and the Allies systematised the obliteration of residential areas and it also abolished the distinction between combatant and non-combatant population (ibid). Also, the bombardment of the cities, with the creation of chaos, aimed at the moral and the psychological collapse of the people (ibid). During the occupation, the city dwellers depended on International Red Cross food imports (Voglis, 1015: 277). Apart from the population, the state was also dependent on foreign economic assistance for its survival (Voglis, 2015: 277).

Photo credits: Christina Papaioannou

Christina Papaioannou (@x.papaioannou_) • Φωτογραφίες και βίντεο στο Instagram

b. Landmark places of the Greek war against the Nazis

The partisan movement was born in Athens but based in the villages, so that Greece was progressively liberated from the countryside (Vulliamy, Smith, 2014). Most of the Greeks have been aligned against the Nazis, battling with whatever means they disposed or devised, yet some places have tied their names to definitive war moments, as the atrocities committed there transcend human conception, or due to the noteworthy resistance of the fighters.

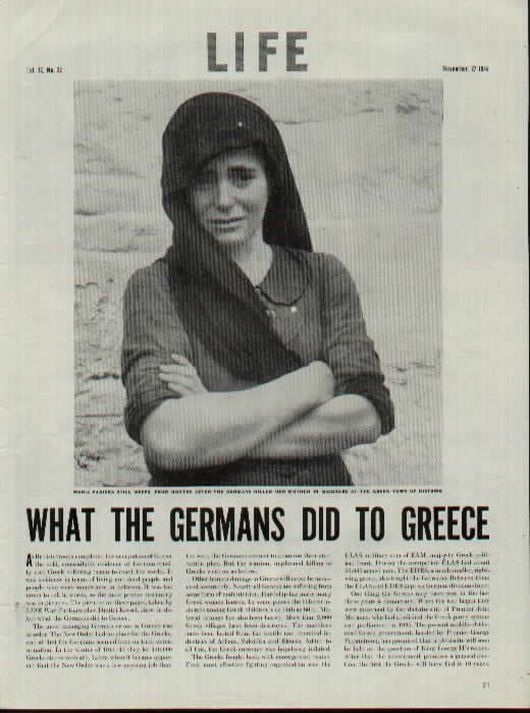

- Distomo: Distomo is a town in Viotia province and “the best-known example of the 110 martyred villages and the annihilation of life during the period of occupation, the period of the war of extermination” (ο.τ., 2013). Four days after the landing of the Allies in Normandy (D-Day), “Germans rampaged through the village, gutting pregnant women, bayonetting babies and setting homes on fire” (Daley, 2013).

The massacre of Distomo was too much to tell in words, so the most precise testimony was in pictures. The Life issue of November 27, 1944, hosted the iconic picture captioned “the weeping face of Distomo” that features Maria Padiska still weeping, four months after the Germans had killed her mother in the massacre at the Greek town of Distomo (Life, 1944). 79 years later, the local community and the descendants of the victims continue to demand justice for the Nazi atrocity (o.τ., 2023). However, the German position is fixed: the issue is considered from a legal point of view to be over and settled with the 2+4 Treaty of 1990 (ο.τ., 2023). “The German government avoids responsibility for the injustice it has caused in Greece; the complacent attitude of an absolute denial of reparations is a blow to the victims of the Nazis,” Sevim Dağdelen MP of the Lefts (die Linke) of the German parliament has declared to Deutsche Welle (ο.τ., 2013).

- Crete: 20th May 1941-1st June 1941 was a landmark date for the evolution of the invasion of the Nazi forces into the Balkans, and a paradigm of determination from the part of the Cretan fighters who saved valuable time for the entire continent, backed by the Allies. After heavy bombardment, the battle of Crete began on 20 May 1941 (Peponas, 2021: 85). Germans had as main targets the three airports of the island – Malene, Rethymno, Heraklion – but faced great resistance by their defenders (ibid). Churchill noted in his memoirs of war: “ruthless attack launched by the Germans. Nothing like it had ever been seen before. It was the first large-scale, air-borne attack in the annals of war” (Churchill, 1986: 447). The invaders suffered heavy losses.

As Churchill recounted, “the battle of Crete is an example of the decisive results that may emerge from hard and well-sustained fighting, apart from maneuvering for strategic positions. The seventh airborne German division was destroyed” (ibid). Of course, Churchill’s fervor to salvage the strategically crucial island of Crete is ascribed to Britain’s urgency to protect its passage and interests to the Middle East. Namely, the defense of Crete was vital for Churchill’s plans (Peponas, 2021: 84). Already in June 1940, admiral Andrew Cunnigham had suggested the occupation of Crete to use the harbour of Suda as a naval base (Roskill, 2004: 204).

Photo credits: Christina Papaioannou

Christina Papaioannou (@x.papaioannou_) • Φωτογραφίες και βίντεο στο Instagram

3. The consequences; a famished country; the post-war ghost capital city of Athens

In the Balkans, the armed, anti-fascist movement of Yugoslavia and Greece, posed a real military problem (Pelz, 2016: 154). In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the Balkans saw the fiercest conflicts (Gluckstein, 2012:37). The Nazi occupation of Greece inflicted suffering comparable to Russia, Poland and Yugoslavia (ibid). After three and a half years of German, Italian and Bulgarian occupation, Greece was left in ruins (Voglis, 2015: 279).

The destruction of the old Sephardic Jewish communities of Alexandroupoli, Komotini, Xanthi, Kavalla, Serres, and Drama was complete (Chandrinos, Droumpouki, 2018: 18). Namely, the Holocaust in Greece claimed a heavy death toll from the Jewish population and witnessed not only mass murder and looting, but also the obliteration of a unique, centuries-old cultural and historical heritage (ibid). As high as eighty-four per cent, the death toll was one of the highest in Nazi Europe (ibid).

During the Axis occupation of the country from 1941-1944, nearly 100,000 people died of starvation (The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, 2020). More than 1,200,000 people were homeless, grain population had fallen by 40 per cent, three-quarters of the merchant fleet was destroyed, most of the facilities at the Port of Piraeus were severely damaged, and not a single railway line was left intact (Doxiadis, 1946: 8-31). 402,000 houses and 1,770 villages were destroyed, leaving 1.2 million homeless (Gluckstein, 2012:38). By the end of the war, about 300,000 had starved to death (Daley, 2013).

One particularly harrowing episode was the famine of 1941-1942, claiming some 250,000 victims and struck Athens particularly hard (ibid: 39). A National Liberation Front (EAM) spokesperson, Dimitrios Glinos, described how many “have been turned into skeletons… Suddenly, they have all aged and black worry and mortal agony is etched in their eyes. The gap between their income and the most necessary expenditure has become fearful. [An] entire wage is not enough to buy food” (Gluckstein, 2012: 39).

Alongside economic havoc and human misery, a violent political conflict escalated as fierce fighting between the communist-led resistance EAM and Nazi collaborators spread to many parts of the country (Voglis, 2015: 279). The Cairo-exiled government, returned to Greece in mid-October 1944, accompanied by British troops (Voglis, 2015: 280).

In the post-war period [the British and the Americans], with the encouragement of the Greek government, got heavily involved in rebuilding the Greek state and in domestic politics (Voglis, 2015: 278). Following the Battle of Stalingrad, the Allies began to draw up plans for the liberated Europe: there were serious concerns that the end of hostilities would be the beginning of a new period of instability, due to the devastation wrought by war and occupation: famine and disease, homelessness and displaced persons, poverty and unemployment, ethnic conflicts and civil strife-all presented immediate dangers and intractable problems (Voglis, 2015: 278).

4. Artistic works inspired by the war

The conflict, the war and the occupation are a black page in Europe’s history. As every destructive event, it became the ground for artistic production and philosophical reflection. Art’s task has always been the discussion of unresolved conflict and dilemmas that seem immune to reasonable explanation.

- Captain Corelli’s mandolin (film). Although the film whitewashes the Italian occupation of the Ionian islands, maybe out of proportion, Madden’s-directed movie ends up being a deeply anti-war movie. It is a hymn to the genuine care for the Other. Set in idyllic Kefalonia, the performances of the entire cast, skyrocketed the movie. Fairly, as it handles highly complicated and inexplicable, yet human feelings, with grace and honor for both sides.

- Cloudy Sunday (Ouzeri Tsitsanis): An autobiographically-inspired cinematic masterpiece. It recounts the days of the composer and musician Vasilis Tsitsanis, during the occupation of Thessaloniki, where he was living and working at the time. The outstanding performances, the inspired aesthetics, the exceptional music of the film, make it unique in the genre.

- Deep Soul (Psychi Vathia): The movie is directed by Pantelis Voulgaris. The plot develops following the relationship of two brothers, led by self-sacrificial love and care, though divided in the war front. During the civil war, in Grammos mountains of western Macedonia, the 14-year-old Vlassis, is recruited by the communist, Democratic army, whereas the 17-year-old Anestis is fighting on the side of the National Army, after their father has died and they have been separated from their mother. The movie narrates what Voulgaris calls “the last act of our nation’s drama.” Also, the cinematic swansong of the heavily awarded actor, Thanasis Veggos, who died on the 3rd of May 2011.

- La Vita è Bella: A timeless, anti-war cinematic masterpiece. The unique and shocking use of humor, its tricky balances, the breathtaking interpretation of Roberto Benigni, awarded the movie three Oscar statuettes, in March 1999. A loving father cherishes the last days of his life, close to his little son, enclosed in the deathly walls of Bergen-Belsen concentration camp.

- The Island (Victoria Hislop): Book and TV series. In literature and cinematic creation, a significant historical event is either at the spotlight of the plot, or it plays a crucial role to the plot, defining the movements and decisions of the characters. Other times, the historical event lies at the background of the story, ascribing to it a specific style and sentimental underpinning. Although the Island is not a story based on the war, the events of the invasion, the occupation and the eventual liberation, underlie the storyline, enhancing the aesthetic and narrative value of Victoria Hislop’s masterpiece.

Photo credits: Christina Papaioannou

Christina Papaioannou (@x.papaioannou_) • Φωτογραφίες και βίντεο στο Instagram

5. The aftermath of the war; the initiation of the civil war and the continuation of the bloodshed in Greece

Between World War I and World War II, modern guerilla warfare has become an overall political, economic, social, and military framework for ‘total war’ (Boyd, 2018). As the battle lines converged on Berlin in the waning days of WWII, fighting and violence erupted across the liberated Europe; In Athens, the bloody events of Sunday, December 3, 1944, initiated a brutal civil war, worse than anything the continent would see for another half-century (The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, 2020). The dramatic events marked the culmination of three long years of suffering for Greece (ibid).

By 1942, Greek resistance groups, including supporters of the deposed regime of Ioannis Metaxas, conservatives, radicals, communists, had begun fighting the occupiers-and each other (ibid). After the Italian surrender, in September 1943, it was not only retaliation against the German authorities that flared up, but also, retaliation among Greek groups of the Hellenic Resistance Frontier (EAM-Εθνικό Απελευθερωτικό Μέτωπο) and the smaller urban resistance groups which, in view of the threat of retaliation, refuged to the occupation forces and the armed collaborationists (Φλάισερ, 2015: 271).

The mutual suspiciousness after the German retreat of October 1944, inflamed the civil war during the battle of Dekemvriana; (Φλάισερ, 2015: 217). The Varkiza agreement of February 1945 turned out to be an inadequate peacemaking means; the climaxing opposition led to a full-scale civil war (Φλάισερ, 2015: 217). Bereft of Soviet support, the EAM went through the motions of compromised with the British, but soon broke faith, distributing propaganda, fomenting unrest and forming armed cells; open fighting between ELAS forces and anti-communists broke out (The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, 2020). The better coordinated and ruthless EAM seized control of much of Greece, except for Crete (The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, 2020). Britain’s active participation shifted the balance against EAM (Φλάισερ, 2015: 271).

In the autumn of 1946, many villagers moved to the cities to have access to the supplies, thereby constituting a new wave of internal refugees that grew to several hundred people in the civil war years (Voglis, 2015: 284). In April 1945, Athens ended up hosting at least 300,000 internally displaced persons trying to escape from the guerilla war that was raging in the province (United Nations Archive, 1945). At the end of Dekemvriana, thousands had been killed; 12,000 leftists were rounded up and sent to camps in the Middle East (Vulliamy, Smith, 2014).

Just like in all fratricidal conflicts, the damage inflicted has been an extensive and multilayered trauma, bequest to the following generations. From 1947, Greece became a country of restricted sovereignty (Voglis, 2015: 292). The Greek civil war climaxed in August 1949, at the final communist stronghold, the massif of Grammos, near the Albanian border (The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, 2020). The final assault on Mount Grammos, backed by helldivers dropping napalm, destroyed the remnant of the rebel army (ibid). The Greek government forces suffered about 48,000 casualties from 1946-1949; death squads on both sides murdered thousands of civilians, and many more died from brutality, disease, and starvation; some 158,000 Greeks may have died altogether, because of the civil war (ibid).