By Maddy Constantine.

Perceptions on belonging to the Greek diaspora of Australia are shifting. As a second-generation Greek-Australian myself, and as one who has also felt inextricably tied to her heritage, I sense a seismic shift in how I, and those like me, identify as a part of this group.

We, children born in the 90s and 00s, championed an indifference and neglect towards our cultural DNA in our coming of age years. This has now transformed into us actively seeking out forgotten elements of our identity as young Greek-Australians.

Here, I endeavour to uncover the reasons for the shift.

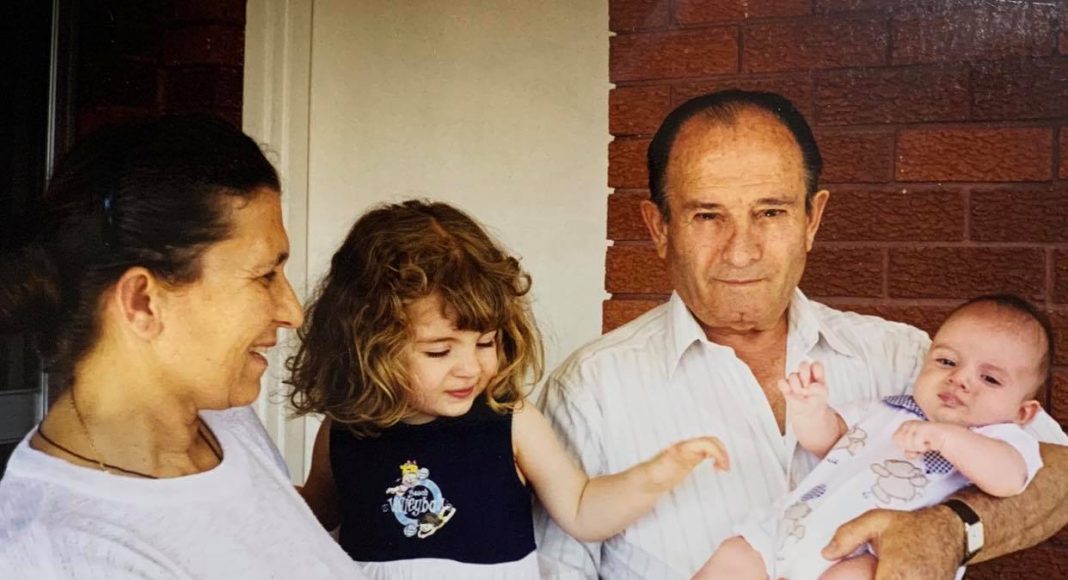

As a small child virtually raised by Yiayia Effie and Papou Trevor on the fringes of Canterbury and Earlwood, a highly Greek-populated area, the values I was raised with were nothing new to me. Everybody went to Church on Sunday, Greek dancing on Wednesday and there was never a short supply of family gathering, or “trapezia” as Pappou used to call it. So heavily influenced by the Greeks who enrolled in the catchment was my public primary school that Greek language class was embedded into the school curriculum, and Orthodox scripture was taught every Tuesday following lunch by none other than my own Yiayia.

I can vouch for many of my fellow Greek-Australians millennials who experienced an almost identical childhood, and took it for granted. It wasn’t until I grew older, moved to different high schools, universities and then into the workforce that the “Wog Bubble” burst to reveal many more diverse characters and life experiences, so very different from my own.

I had been subject to a normal level of schoolyard cattiness, but I was never attacked or isolated because of my Orthodox faith or ethnic heritage until I stepped into a school with a largely white population. Kids who couldn’t tell the difference between a kebab and a souvlaki, hommus and tzatziki, or a Greek and an Italian.

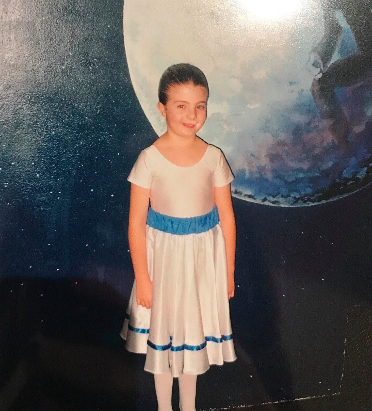

Suddenly my heritage, the way I was raised and taught to behave was an object for ridicule. An identity crisis ensued, where I bargained between fitting into my new school and suppressing who I inherently was as a person. A particular memory that stands out is when I was called a “Jesus Freak” in Extension English by a fellow student, for being able to answer a question about Shinto Buddhism. And let’s not forget the countless times I had to eat lunch alone so as to avoid the questions related to what “exotic” food I was eating that day.

At the same time I strived to keep a low profile and “tone it down” I witnessed kids who grew up in the Greek communities with me start to shy away from their “wog” heritage. Attendance at Easter mass amongst the teens dropped dramatically, a midnight tradition once cherished by those lucky enough to experience it. A few of my friends dropped out of Greek dancing, and many more stopped listening to Greek music all together. Only “losers” went to the Annual Greek Festival in Darling Harbour each year, and the few of us who could speak Greek found it harder and harder to communicate with our non-English speaking grandparents.

When Greek friends made fun of me for wanting to play some Greek music in the car it saddened me and left me wondering, why? Even at university I was hesitant to join the Hellenic Society on campus in fear of being associated with “overly-patriotic” Greek kids (turns out years later I would become great friends with a few of them), even though a part of me wanted to share my love for Greek culture with others my age.

Looking back at these times I can’t help but marvel at how things have changed over the years. More and more I am noticing my generation start to embrace their heritage again in different ways. Some frequent dedicated “Greek Nights” at the nightclubs in Sydney. Others, travel to Greece on yearly pilgrimages to visit the villages of their parents and grandparents and experience the sun-soaked wonder of a Greek summer. These are just a few specific examples but in general it seems we are less ashamed, and more proud of the place that has shaped our cultural identity, and there are many reasons why.

One popular sentiment amongst young Greek-Australians is the feeling that our ties to Greece are directly related to the connection we have with our grandparents. A majority of our grandparents were the first to migrate to Australia after World War Two on voyages such as the “Patris”. They settled here and weaved the Greek culture into how they raised the generations to follow. For many of us in the second generation, our grandparents practically raised us, and were the ones to teach us most of the language as we know, as well as some of the “Greek-lish” words we have come to use such as “petrelio” and “toileta”.

As I get older and my grandparents age and start to pass away, I find myself suddenly desperate to learn everything they know. Their recipes, their vocabulary and stories of their youth. I am not alone in this. Countless times I have heard fellow Greeks say things like “I wish I spoke to my Grandparents more” and “nobody made pita like my Yiayia”. This I believe is one of the driving forces for us clutching on to our heritage more fervently than ever.

Another leading cause for the revival of Greek culture in our communities is the arrival of new migrants from Greece following the crash of the Greek economy in 2010. Since then Australia has experienced an influx of Greek migrants on temporary and permanent visas, seven-fold for those on student visas and a four-fold rise in family migration. As these people arrive on our shores they have settled and started businesses of their own, much like the “milk-bar” generation of post-war Greeks striving for prosperity in the “Lucky Country”.

These people, however, are not carrying the torch alone. Amongst the new wave of migrants and business owners culturing our city with authenticity and passion comes the pioneers in the younger generations, making names for themselves in the Australian-Greek scene.

These emerging pockets of Hellenism in the fabric of our multicultural society are deeply encouraging to a person like me, so passionate to keep the stories and traditions of my Greek heritage alive. We must embrace who we are and never be ashamed of just how much our lives are enriched by the ability to belong to the Greek community of Australia.

In my humble opinion, the thing us Greek-Australians have to be proud of the most, is the inherent sense of “Philotimo” we can share with others. Philotimo, a word packed with so much meaning and essential to the Greek way of life, can change the world through its teaching of selflessness and honour for doing good, often symbolised by inviting a stranger into your home to experience love, shelter and kindness, before you.

The “Greek Revival” in Australia is in its early phases, there is so much more we can do for the Australian community in the years to come.