By Anastasios M. Tamis

The Prespa Agreement (17.6.2018) was a bad deal, but it was much better than the lack of a specific policy, the untimely political improvisation, the sloppiness, the lame diplomatic acrobatics that have existed since 1913. Let’s look briefly at this development.

With the Treaty of Bucharest (1913) and the double exchange of populations, which followed the Balkan-Turkish War (1912-1913) and the Greco-Bulgarian War (1913), those with a Bulgarian-Slavic conscience moved from the regions of Macedonia and Thrace under Greek sovereignty and settled in Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.

Later, in 1945, the recognition of Southern Serbia as “Macedonia”, and an indispensable state of Yugoslavia, removed from Bulgaria the dream of claiming the “Bulgarians” of Yugoslavia and thus forming a Greater Bulgaria on the back of Greece.

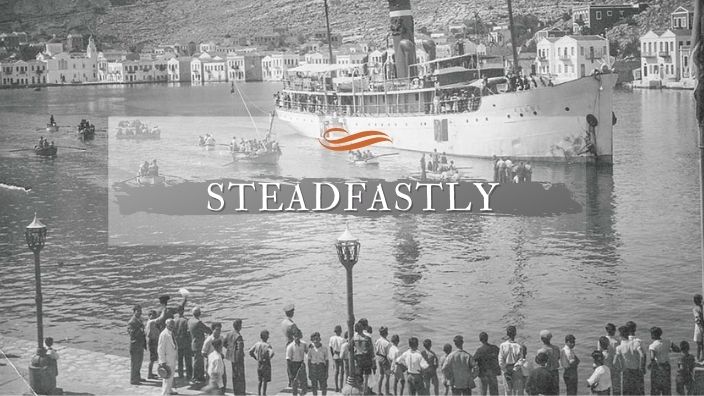

However, despite the exchange of populations, a small number of Bulgarian-speakers of Greek Macedonia with a purely Bulgarian conscience and language, remained or even hatched on our northern borders, demanding autonomy, and secession from Greece. Many of them, along with Bulgarian-speaking Greeks of Macedonia, emigrated after 1913 to the USA and after 1924 to Canada and Australia.

In Australia, from 1931, they founded their own Bulgarian church and their own Bulgarian clubs in Perth and later in Melbourne and Sydney, in a polemic move against Greek Macedonians who had already founded their own club in Perth in 1930, Alexander the Great.

During and at the end of the Second World War, the Bulgarian-conscious separatists began to discover their national consciousness and from “Bulgarians” who had been declaring themselves until then, they began to identify themselves simply as “Macedonians”. Their Bulgarian Church in Melbourne, from a Bulgarian Church, was transformed into a “Macedonian Church” and their language, which until then, even among them they called “Bulgarski“, “Starkski” and “Ponasi”, now also became “Macedonian“.

During the late stages of the Greek Civil War (1946-1949) the leftist leaders of the Greek Democratic Army allied with Bulgarian-speaking separatists from Skopje and Greece and included them militarily in their forces against the Greek Army, promising that if the outcome of the war was to be victorious, they would secede part of Greek Macedonia and integrate it into an autonomous Bulgarian-Slavic Macedonia.

However, the defeat of the Bulgarian-Macedonian separatists in 1949 in Grammos and their exodus from Greece, Yugoslavia, and the countries of Eastern Europe, was followed by their numerous settlements in Canada and Australia. In the new countries where they settled (it is estimated that 35,000 settled in Australia), they first sowed hatred against Greece among their children and grandchildren, the hatred against the Greeks, who supposedly deprived them of their homeland and their villages, and eighty so many years they continue their irridentist struggle against everything that is Greek.

Greece, no longer having Bulgarophiles, former Greeks, on its territory, never saw the problem as a political and diplomatic priority. For Greece this problem has always been administrative. It was never taught in schools, it had no emphasis on interstate and bipartisan meetings, it was a degraded, nebulous, undefined, and largely unknown subject, a taboo.

On the contrary, in Skopje and their Diaspora, the Bulgarophiles taught their irredentism, published unhistorical books against Greece, taught that they were descendants of Alexander the Great, gave their monuments a Hellenic genre (they were also philhellenes, therefore), appropriated Aristotle, Philip, Hellenic ancient history, even though they knew very well that their ancestors never lived in the Balkans until 1000 years after the Macedonian Kings of the Greeks.

In Australia, where they live, they pre-empted the Greeks, both in life and in death (desecrating their tombs with revolutionary slogans on their tombstones in the Bulgarian dialect, with Greek logos and signs), they desecrate Greek churches, they write slogans of violence and terror on walls, they burn Greek flags, they teach their children about their great ancestor Alexander the Great, the Inskender, they organize groups with the sun of the Greek Macedonian Royals, they terrorize the Greeks in the stadiums and workplaces.

For Greece this problem has always been a conjectural and speculative; for the Greeks of Australia, Canada and the USA had been a concrete and practical, a problem of trenches. The Greeks of Australia cohabitate with the Bulgarophiles and their brothers, the citizens of Severna Macedoniya, they live together in the same suburbs, their children attend as students the same schools, they share in collaboration the same offices; in Greece the political world and the Greeks did not experience any problematic activity; hence, they did not appreciate it as real.

A solution had to be found to make things peaceful. The younger generations, who may not have been infected by the germ of Bulgromanic hatred, should have the opportunity to live in harmony, as Balkans, as neighbours, as like-minded people of the same religion and as fellow human beings. And the difficult political decision was slow because it wanted boldness, it needed tolerance in the negotiation, it wanted progressive motives.

Compromise has no winners; everyone is to lose. The decision on a give-and-take agreement also needs to have an internationalist mindset, when negotiating national issues. It rightly came because of the leftist forces, the sufficiently internationalists, at a time when they both ruled their two countries in Athens and Skopje.

The agreements must be applied as they should: ‘pacta sunt servanda’, to have credibility; so that there can be agreements; this is the fundamental principle of international law. With the signing of the Prespa Agreement only by Nikolaos Kotzias (17.6.2018) and its ratification by the Greek Parliament (25.1.2019) the nomenclature issue was solved, as-like, with the use of the term “Severna Makedonija” (North Macedonia); with this name the Skopje joined the UN and became the 30th member of NATO in March 2020. This nomenclature “Severna Makedonija” has been accepted as a constitutional name both for external and internal use. However, this name is not a single word; it is two words, which means, whoever wants, can easily use only the second one.

Thus, after the debacle suffered by the social democrat Zoran Zaev in the municipal elections of Sunday, 31 October 2021, he directly announced, the same evening, that he would resign (then change his mind) from the position of Prime Minister of “Macedonia”, as we all heard in the news. He obviously wanted to join here, for electioneering reasons, with the nationalist party VMRO-DPMNE, the leader of the main opposition, Christian Mitskoski, who, already in the run-up to the elections, called his country simply “Macedonia” and stated that, as a government, he will not respect the Prespa Agreement and will not use the nomenclature “North Macedonia” within his country, as the revised Constitution of his newly established country clearly states.

The Agreement also explicitly states that the North Macedonians have nothing to do with the culture and historical life of ancient Macedonia, which is purely Greek, that they will not use Greek symbols, the Sun of the Macedonian Kings, and that they will rewrite the books of their history, according to the historical truth and not the propaganda of the past.

However, in Australia, members of their diaspora, Bulgarophile, ex-Greeks and their communal organizations are accustomed to disobeying their Constitution, of trampling on the agreements signed by their leaders, of showing disrespect for their own history, accepting as their supposed own, everything that still has to do with Greece and the Greeks.

Perhaps it will take time for them to understand that the game is now over. And, it is in everyone’s interest to implement what has been agreed, so that the people can live together in an atmosphere of calm and cooperation. This is their common interest.

*Professor Anastasios M. Tamis taught at Universities in Australia and abroad, was the creator and founding director of the Dardalis Archives of the Hellenic Diaspora and is currently the President of the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies (AIMS).

READ MORE: The problem of succession: Why young people don’t follow?