By Dr. Themistocles Kritikakos (Historian)

Earlier this week, the Greek-American organisation, the Eastern Mediterranean Business and Cultural Alliance (EMBCA), held its third Forum on the Greek Genocide—a subject long confined to the margins of history. The event brought together scholars and researchers to explore the historical processes that contributed to the persecution and destruction of Christian minorities—Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians—during the final years of the Ottoman Empire.

Moderated by EMBCA President Lou Katsos, the panel presented research examining the political and ideological dynamics that shaped this period of mass violence and displacement, which resulted in the deaths of an estimated three million Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians between 1914 and 1923, including more than 750,000 Greeks from Asia Minor (including Pontus) and Eastern Thrace.

At the forum, my presentation, From Empire to Nation-State: Nationalism, Ethnic Homogenisation, and the Elimination of Minorities in the Late Ottoman Empire, examined the institutional and ideological drivers of the persecution of Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians from the 1870s until 1924.

Several distinguished academics and researchers contributed to the forum, including Lou Ureneck, retired journalism professor at Boston University and author of The Great Fire; Dr Vasileios Meichanetsidis, author of The Genocide of the Ottoman Greeks; Dr Fatma Müge Göçek of the University of Michigan, author of Denial of Violence; Dr Theodosios Kyriakidis, Chair for Pontic Studies at Aristotle University of Thessaloniki; and Savvas (Sam) Koktzoglou, co-author of The Greek Genocide in American Naval War Diaries.

Reconceptualising Genocide as a gradual and evolving process

My presentation traced the transition from imperial pluralism to ethnic nationalism in the late Ottoman Empire, highlighting the systematic elimination of Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians. It demonstrated that genocide emerged through interconnected phases of state-led persecution characterised by demographic engineering, ideological radicalisation, and cumulative violence under successive regimes.

Drawing on the work of leading genocide scholar of the late Ottoman period, Taner Akçam, I argued that genocide is best understood not as a series of isolated events, but as a cumulative and evolving process. It begins with ideological dehumanisation and progresses through systematic administrative measures. These include legal discrimination, surveillance, propaganda, economic boycotts, demographic restructuring, and bureaucratic marginalisation, ultimately culminating in mass violence and extermination.

The Ottoman Empire governed its diverse population through the millet system, which granted limited autonomy to religious minorities such as Christians. Despite this, Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians, were still classified as second-class citizens. However, they had deep historical roots in the region and played vital roles in the empire’s cultural and economic life.

From the nineteenth century onwards, political shifts began to challenge this multi-ethnic system. The Tanzimat reforms (1839–1876) sought to modernise the empire and grant equal citizenship to all subjects, but these efforts provoked conservative backlash and ultimately failed to resolve minority grievances. The 1878 Treaty of Berlin, which endorsed reforms for Armenians following the Russo-Ottoman War, intensified suspicions that Christian minorities were aligned with foreign powers.

Under Sultan Abdulhamid II (1876-1909), authoritarianism increased, culminating in the Hamidian massacres of 200,000 Armenians and 20,000 Assyrians between 1894 and 1896. The 1908 Young Turk Revolution briefly raised hopes for equality. However, the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP)—the political party of the Young Turks—soon asserted a centralised, nationalist agenda amid growing political instability in the empire.

Following the Adana massacres of approximately 20,000 Armenians in 1909—amid political tensions between supporters of Sultan Abdulhamid II and the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), and broader challenges to reform within the empire—the CUP, at its 1910 and 1911 congresses, advocated the use of force to achieve Ottomanisation, viewing Christian minorities as obstacles to preserving an empire in crisis.

Territorial losses and the mass exodus of Muslims following the Balkan Wars (1912–1913) contributed to the radicalisation of the Young Turks, who began to view Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians as unassimilable internal enemies. The persecution of Greeks in Eastern Thrace in 1913 marked an early manifestation of this shift, which escalated further in both Eastern Thrace and Western Anatolia in 1914. These events escalated the broader process of Turkification, characterised by land confiscations, mass violence, and the expulsion of Christian minorities.

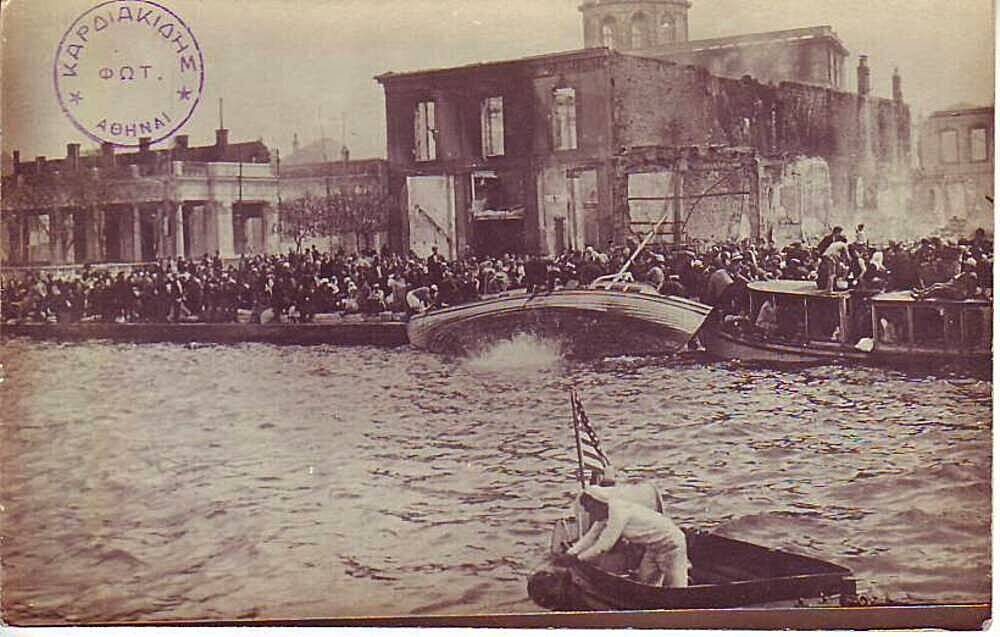

Between 1914 and 1923, Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians endured a coordinated campaign of persecution orchestrated first by the Young Turks and later by the Turkish Nationalist Movement. This campaign encompassed the First World War (1914–1918)—although Greece only entered the conflict in June 1917—and continued through the Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922). It included targeted violence against Greeks in Eastern Thrace and Western Anatolia, as well as Assyrians in Eastern Anatolia in 1914; the Armenian Genocide of 1915; the persecution of Pontian Greeks in 1916; ongoing violence in Pontus from 1921 to 1922; and the Catastrophe of Smyrna in 1922. While often studied separately, these events were interconnected events within a broader period of displacement and violence that began in the late nineteenth century and culminated in the 1923 Population Exchange.

Despite changes in leadership and variations in how each group was targeted, successive Ottoman and Turkish regimes perceived Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians as unassimilable existential threats and portrayed them as disloyal subjects collaborating with the Great Powers. Through dispossession, deportation, and extermination—driven by nationalist ideologies and internal political struggles—these regimes aimed to achieve national homogenisation.

The concept of cumulative radicalisation closely aligns with genocide scholar Dirk Moses’s notion of the “problem of permanent security,” whereby states, in their pursuit of lasting stability, perceive certain minority populations as unassimilable and persistent threats to national cohesion. Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians—some of whom advocated for reform or autonomy—were viewed as fundamentally incompatible with the preservation of the disintegrating Ottoman Empire and, later, the construction of the Turkish nation-state.

This violence was carried out by central and local Ottoman authorities, military forces, paramilitaries, and local collaborators—including some members of Kurdish and Arab tribes. Although Armenians, Greeks, and Assyrians were the primary targets, other minorities—including Maronites, Antiochian Greeks of the Levant, Yezidis, Kurds, and Jews—also suffered various forms of persecution, a subject that warrants further research.

The Paris Peace Conference (1919–1920) and the Treaty of Sèvres (1920) aimed to redraw territorial boundaries and establish a new order following the breakdown of the Ottoman Empire. Amid these international developments, the Constantinople trials (1919–1920) sought to prosecute and punish those responsible for crimes committed against Christian communities. However, these initiatives collapsed due to shifting political priorities, the absence of a clear legal framework, and a lack of sustained international resolve—ultimately allowing the perpetrators to escape punishment. The 1923 Treaty of Lausanne established new national borders, and the subsequent population exchange between Christians in Turkey and Muslims in Greece contributed to further demographic shifts.

Turkish historical narratives have traditionally emphasised themes of national survival and triumph over perceived internal dissent and foreign intervention. In doing so, it has often sidelined the experiences of minority communities, downplaying or overlooking the extent of their suffering. Violent actions against these groups have frequently been depicted as unfortunate but essential measures to maintain national cohesion or as inevitable consequences of the turmoil and chaos of war.

Through processes of dehumanisation and delegitimisation, minority groups came to be perceived as threats, creating conditions in which genocidal acts were justified as necessary for preserving or restoring state integrity. Nationalism, anchored in ethnic and religious exclusivity, shaped the final decades of the empire and significantly influenced the formation of the modern Turkish Republic through a project of monocultural homogenisation. By fully examining this history through academic research and dedicated education initiatives, we gain vital understanding of the past that shapes contemporary dialogues on intergenerational trauma, accountability, and political recognition.