The Greek island of Crete is renowned for its beauty and ruggedness. Its people’s hospitality and food are also alluring – something which I fondly remember having grown up in an Australian neighbourhood amongst quite a few families from Crete. In all those years though, I never once heard about the Battle of Crete. My only ‘battle’ with Crete was trying to secure a second or third delicious kalitsounaki that Theia Zaharoula, our neighbour, made.

On a Greek group tour to Crete with my family decades ago, we were led to interesting sites like the Samaria Gorge and Ancient Knossos. One of our sons, then aged six, was so impressed with the island that he vowed, “I will live here in Crete one day.” And he did so, going on to study at two Cretan universities in Chania and then Heraklion.

I would often visit him and other parts of the island, meeting locals but again, never once did I hear any mention of the Battle of Crete. My husband had alluded to something about Australians and Cretans having a bond due to WWII. In hindsight, I feel rather sheepish that I didn’t bother to look into the Battle of Crete then, so now I’m making up for lost time…

I visited the War Museum in Athens where I spoke to curator Theofanis Vlachos.

“Greek military history is long and complex so dedicating a section, albeit small, to the Battle of Crete signifies its importance. There is another offshoot of the War Museum near Rethymno at Chromonastiri, which also has relevant artefacts,” Mr Vlachos explains, before further advising me about the battle.

The Battle of Crete began in 1941 on the 21st of May and lasted for 13 days. Allied forces headed by the British were stationed on the island against Hitler’s invading army of around 22,000 troops. British Intelligence did have an upper hand via their Enigma intercepting machine, leading to discovering Hitler’s plans to invade Crete beforehand. This resulted in Winston Churchill ordering further defensive reinforcements – Australian troops (as well as New Zealander and Greek soldiers), bolstering the Allied forces to 42,000 men.

Australian troops in Crete numbered 6,540 of which approximately 500 were killed, over 900 wounded and almost 5,000 taken as Prisoners of War 1. Much of this 2nd ANZAC force included the sons of the first Gallipoli ANZACs.

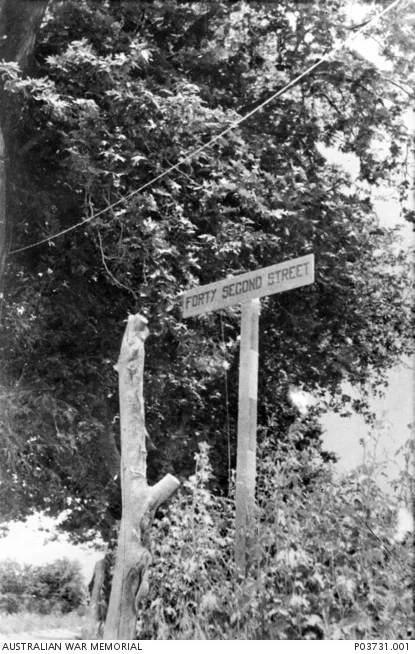

Aboriginal soldier Reg Saunders was involved in one of the many heroic and – as he and another Aussie soldier tell us – dehumanising battles against the German forces; at the Battle of 42nd Street located along the Chania to Tsikalaria road. The Australian and New Zealand force hid in a gully and predominantly using bayonets, lunged at the Germans, causing them to have around 300 casualties.

“I saw a German soldier stand up in clear view about thirty yards [30 metres] away… I can remember for a moment that it was just like shooting a kangaroo… just as remote,” Saunders once said.

Of this same battle, soldier Johnny Peck claimed: “They didn’t just turn and run, they fought back… he was fairly bigger than me and he got me through the arm but he was dead soon afterwards, the German’s bayonets were nowhere as long as ours… I never felt anything, not even relief.” 2

Like many soldiers who were still alive and eventually ordered to retreat from the Germans, both Reg and Johnny went into hiding in Crete and were looked after by Cretan families who courageously risked their lives to help. There are so many factual stories about such incidents, including the monastery of Preveli in Southern Crete where there’s one of the many monuments that pay tribute to the bravery and bond of the Cretans and Australians (and of the other allies).

“The Cretan men, women, children and elderly, attacked the German invaders with anything at their disposal, including pitchforks, rocks, rudimentary rifles, dead Germans weapons, etc. This included attacking the German soldiers dropping down in their parachutes. Paratrooping was a unique feature of the Battle of Crete never attempted before in such numbers by an invading army,” Mr Vlachos clarifies.

“The German forces took advantage of ‘rules of war’ that deemed a civilian killing a soldier to be murder. This led to exaggerated and brutal reprisals towards the Cretan people, continuing until the Germans retreated in 1945.”

Germany did officially win by gaining ground in Crete, forcing the Allies who weren’t killed to retreat. But nonetheless, everyone involved in the Battle of Crete – from the Germans to the brave ANZAC forces, the Greek Army and of course, the local Cretan resistance – were victors as well as losers.

Lest we forget, and strive for peace as an all-consuming, universal goal.

References:

- All figures from Gavin Long’s Official Histories (Long, G 1953, Second World War Official Histories: Volume II – Greece, Crete, Syria, 1st ed, Australian War Memorial, Canberra) at pages 315 and 316.

- Video lecture by Prof. Monteath, ‘The Battle of 42nd Street | Seminars 2022, Greek Community of Melbourne, 43:02 -43:43)