By Kathy Karageorgiou.

In my part-time work here in Greece, I have come across a sweet occurrence. While inspecting properties, many tell me that they are considering buying for their daughters. Some of these girls are still toddlers, while others are in their early 20s.

These parents are enacting the old tradition of proika (προίκα, in Greek) or dowry – in English, in the form of a substantial gift of property in this case, for their daughter(s), in lieu of her eventual marriage. I should be so lucky I thought, as I didn’t get any proika, but with our hard yakka, luckily my husband and I managed to accrue our humble abode.

A more chatty client, a mother looking to secure her daughter an abode in the form of an apartment, confessed: “I want to help my daughter, and also protect her in case her husband turns out to be no good.”

In such a scenario of a partner gone wrong, the wife (with the proika) gets to keep the house outright. The ‘bad husband’ is sent on his merry way, as she waves goodbye to him tearfully or not, as he himself perhaps decided to flee from the marital union.

Proika, which comes from the Ancient Greek word pro + ikneuomai, meaning to come before (the wedding), has often been interpreted differently to that of a ‘sweet occurrence’ that I interpret. Many say proika (which was actually entrenched in Greek law in the past), deemed a woman a material possession. In the not so distant past a ‘decent’ proika included, apart from a house, money – English gold coins (lires) or plots of land and even livestock.

It is noted in various documentations of the proika custom, that many grooms-to-be (and their families), demanded a high price for the dowry, or the marriage would just not happen. Such cold-hearted calculating was often an acceptable agreement or business transaction, as more often than not such jaunty bargaining grooms (and their families) wanted to match or increase their own familial wealth. In such cases love fell by the wayside, as the marriage union became an issue of socio-economic practicalities and/or status.

Historically, the proika institution got to a point where wealth was accruing in a few families only, whereby in the 6 century BC, the Athenian statesman Solon banned all dowry deals. Enacting it in law, he replaced corrupting proika with a more modest form of it: A woman’s proika was to be 3 garments and a few household items.

In fact, in more Ancient Greek times, it was the man who gave the proika to his bride to be, as stated in the Iliad during the heroic 12 century BC period. In order to become a worthy suitor, a man had to prove his prowess in hunting, agriculture, athletics, art/culture and in bravery, like the Argonauts and Trojan warriors. Only then could he take a wife, consequently offering her gifts such as gold, property and farm animals as his show of his merit as a husband.

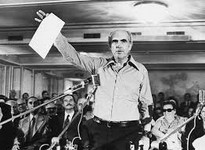

Meanwhile, and all the while, our great philosophers Aristotle and Plato, considered proika barbaric and uncivilised. Nonetheless, in the 1 century AD the Roman emperor Augustus had a patriarchal turn and re instigated bride to groom proika, which continued into the Byzantine and Asia Minor culture and beyond, into modern Greece … until 1983. This was when Prime Minister, Andreas Papandreou of PASOK banned proika outright in codified law.

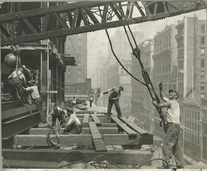

The proika institution throughout the ages had put much pressure on families of the bride, particularly if they were poor or had more than one daughter. This proika tradition was so deeply entrenched in our Greek society of the previous century that it was the reason for some of our Greek migration histories to Australia. Young men who had sisters would migrate, not only to Australia but to the USA and Canada for example, in order to make money to help their families in Greece with the dowry.

There are also cases of Greek women migrating afar – to Australia, etc, due to the proika dilemma. These women were from poor families of often many daughters, whose parents could not afford to give them the often dreaded proika.

And of course, not all men were proika-hounds! Those truly noble men who wanted their girl without proika would often be discouraged from marrying her by his family and surrounding community, as it was considered disgraceful. I know of such a case from a village in Lefkada, where the bride and groom eloped and came to Australia, making their own way in the world – kudos to the ‘new world’ for providing ample employment as a ‘lucky’ country back then.

Today proika rituals still exist among Greek Australians in Australia (apart from in Greece). I have heard of girls being gifted a house or help with the deposit on a house. But economic constraints (as well as a minority of our parent’s generation who disregard this custom), nonetheless see many of us (second generation Greek Australians) having a μπαούλο (baoulo) – a glory box.

Like me, being the proud owner of a baoulo too! A gorgeous, rosewood one with Asiatic-scened carvings encompassing an exotic brass lock. In it my mother would shyly and discretely add homewares like beautiful, excellent quality tablecloths and sheet sets and some of her gorgeous embroidery work to be framed.

I wasn’t allowed to peer inside my baoulo (a bit of a Pandora’s box before marriage I guess), but me being cheeky and curious, did so very briefly and quickly.

And many, many years later I still recall that beautiful, red and white, unusually patterned, blanket on top of the other hidden treasures which I didn’t have the time or courage to thoroughly investigate. My mum must have brought this hand woven, woolen blanket from her village – in that one suitcase (that proverbial one suitcase all our parents refer to as their sole accompaniment on their trip to the Antipodes).

So, I revert to and correct my reference at the beginning of this article of not getting any proika. I did get proika; of the best and most soul-full kind, straight from my mother’s or grandmother’s heart. Stuff that is priceless these days, in our mass produced, commercialised world where things aren’t intended to last for long – let alone for a lifetime like my precious proika. Thanks Mum.