By Dean Kalimniou

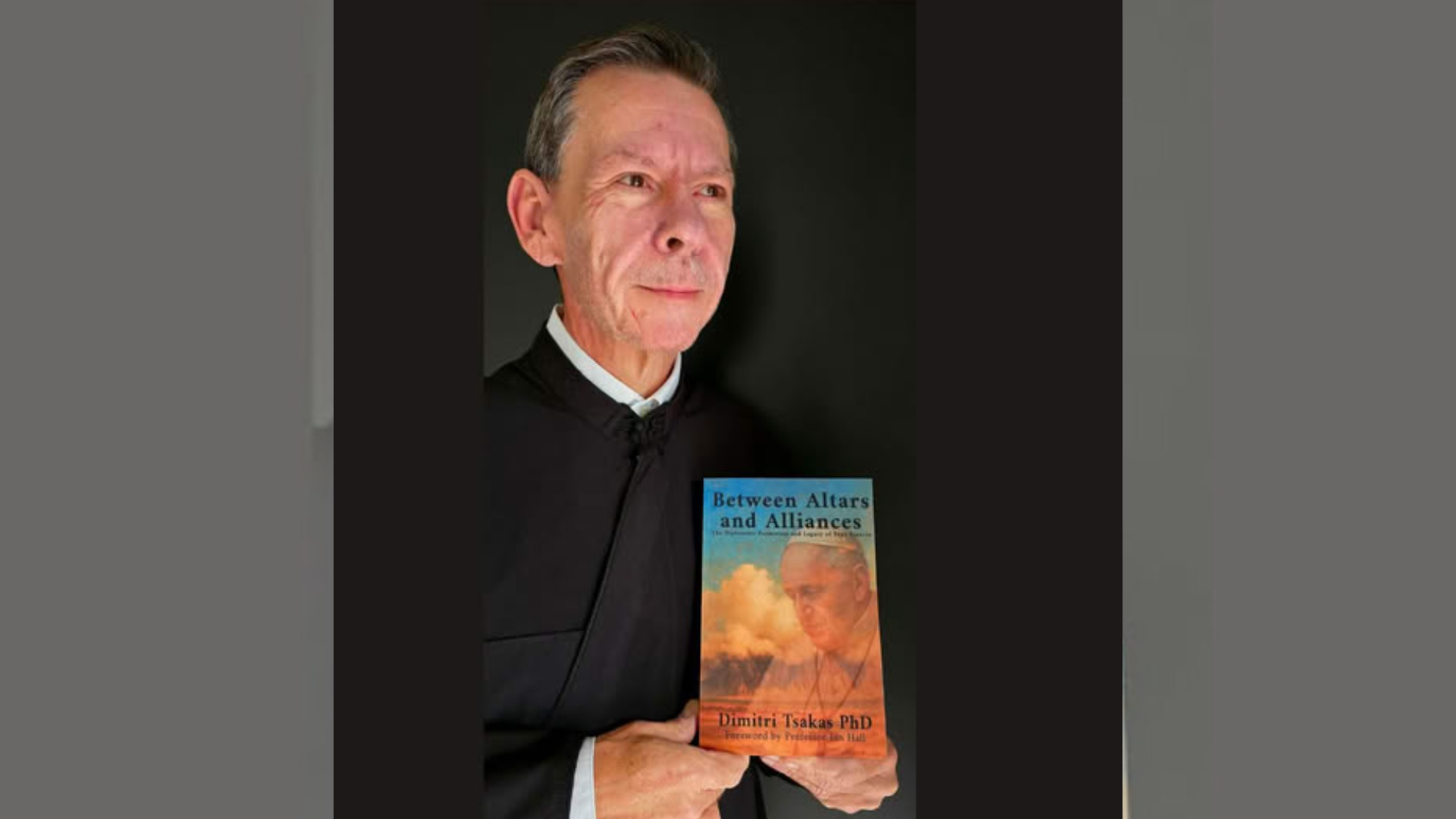

In his recently published “Between Altars and Alliances,” Father Dimitri Tsakas, a Greek Orthodox priest, offers a rich, expansive, and intellectually sophisticated exploration of Pope Francis’ diplomatic legacy.

This is no superficial biography nor apologetic hagiography. Instead, he furnishes the reader with an interdisciplinary analysis that draws equally from theology, international relations theory, political history, and critical theory. The result is a work that not only sheds light on the inner logic of Francis’ unconventional diplomacy, but also calls into question the inherited assumptions underpinning papal statecraft in the modern era.

At the heart of the book lies a compelling argument: that Pope Francis did not merely engage in diplomacy as an ancillary function of the papal office, but redefined it as a mode of ecclesial presence in the world, as a form of spiritual encounter and discernment rather than geopolitical manoeuvring. This paradigm, according to Father Dimitri Tsakas, emerges from a confluence of Francis’ Jesuit formation, his Latin American political context, and his commitment to the full implementation of the Second Vatican Council.

Father Dimitri Tsakas carefully traces how Francis’ diplomatic ethos is shaped by Ignatian spirituality. Here, diplomacy is primarily about discerning the signs of the times, privileging reality over idealism, and acting from the margins. The influence of figures such as Romano Guardini and Gustavo Gutiérrez becomes palpable in this work, where paradox, ambiguity, and patience, rather than being seen as flaws in Francis’ approach, are deliberate features of a relational politics grounded in encounter, not confrontation.

The ground-breaking study situates Francis squarely within the tradition inaugurated by Vatican II. The author convincingly argues that Francis sees the aggiornamento of the Council not solely as a moment in ecclesial history, but as an ongoing imperative. His diplomacy thus is dialogical, inclusive, and unafraid to enter the world’s wounds. The model of Church as “field hospital” becomes more than a metaphor, it structures the very grammar of Francis’ international engagements.

Father Dimitri Tsakas’ engagement with diplomatic theory is nuanced and incisive. He situates Pope Francis within the tradition of soft power diplomacy, yet expands it beyond Joseph Nye’s formulation. For the author, Francis’ diplomacy is not merely about attraction or legitimacy, but about presence, memory, and witness, drawing on theological rather than strategic categories.

Engaging constructivist and post-structuralist international relations theory, the author shows how the Holy See under Francis challenges the logic of geopolitical hegemony. Rather than acting as a power-maximiser, the Vatican becomes a norm entrepreneur, advancing alternative frameworks grounded in multilateralism, nonalignment, and a theological anthropology of encounter.

While Father Dimitri Tsakas does not explicitly engage critical theorists such as James Der Derian or Cynthia Weber, his account gestures toward a reading of Francis’ diplomacy as deeply symbolic and performative. He invites readers to consider how the pope’s public gestures—his silent prayer at the separation wall in Bethlehem, his embrace of refugees, his meetings with Patriarch Kirill and Grand Imam al-Tayeb, operate within theological and liturgical registers, rather than conventional geopolitical scripts. In this light, Francis emerges not merely as a statesman, but as a moral interlocutor whose rituals of presence challenge the logic of Westphalian diplomacy and unsettle the norms of global governance.

In this respect, the pontiff’s preference for a multipolar world is not a tactical response to declining Western influence, but a theological commitment to pluriversality, a world composed not of one centre and its satellites, but of many voices, many centres of gravity, all oriented towards the common good. This vision aligns with the decolonial critique advanced by thinkers such as Walter Mignolo or Enrique Dussel, who call for a shift from universalism to diversality. Francis’ diplomacy, as the author describes it, operationalises this shift by decentralising ecclesial authority, amplifying non-European perspectives, and affirming the dignity of peripheries.

This approach can be fruitfully read through Michel Foucault’s theory of power as relational and dispersed. As the author suggests, Francis’ diplomacy resists the vertical hierarchies of both ecclesiastical tradition and secular realpolitik. Instead, it exercises what Foucault might call capillary power, influence that moves through diffuse, informal channels, privileging proximity over domination. This power manifests in pastoral visits, symbolic gestures, and acts of solidarity that bypass conventional statecraft while subtly shaping global consciousness. In this light, Francis is not merely a soft power actor, but a practitioner of parrhesia: one who dares to speak truth from the margins within asymmetrical structures.

One of the great strengths of the book lies in its use of three case studies: Francis’ diplomatic engagement with the United States, Russia, and China. Each is approached not merely as political history but as a meditation on the tensions between diplomacy and conscience. In the case of the United States, Father Dimitri Tsakas highlights Francis’ dual posture of alignment and critique: affirming American democratic ideals while challenging economic exclusion and militarism. With Russia, the author probes the risks and significance of the 2016 Havana meeting with Patriarch Kirill, framing it as a tentative gesture toward healing the millennium-old schism, while remaining alert to the complicity of the Russian Orthodox Church in Kremlin geopolitics.

The China chapter is perhaps the most ethically provocative. The author does not avoid the controversy surrounding the 2018 Provisional Agreement. He acknowledges concerns from underground Catholics and human rights advocates, but interprets Francis’ decision as driven by a long-range pastoral vision. Diplomacy, in this case, becomes a form of ecclesial kenosis, a strategic self-emptying in hope of sustaining communion. Though Tsakas does not explicitly cite political theologians such as William Cavanaugh or Leonardo Boff, his work gestures toward the same questions: How does the Church navigate the tension between institutional adaptability and prophetic witness? In inviting readers to reflect on these dilemmas, the author opens space for a deeper theological engagement with the practice of diplomacy under authoritarian regimes.

While not explicitly engaging postcolonial theory, Father Dimitri Tsakas’ account invites a critical reading through that lens. Francis’ formation in postcolonial Argentina, and his deep suspicion of hegemonic structures, resonates with the concerns of theorists such as Homi Bhabha and Frantz Fanon. Although the author does not cite them explicitly, his emphasis on Francis’ resistance to binary logics, his decentring of European authority, and his preference for the margins suggests a decolonial ethos at work. One might interpret Francis’ diplomacy as a form of pastoral pluriversality: opposed to imperial universals and rooted in the dignity of multiple centres of moral authority. A more sustained dialogue with liberationist and postcolonial scholarship, particularly as applied to ecclesiology, could further illuminate the theological radicalism implicit in the author’s narrative.

This raises a pressing question: what might this model of diplomacy mean for the Orthodox Church? Father Dimitri Tsakas is suggestive rather than prescriptive. He observes that Orthodoxy, lacking a centralised juridical authority like the papacy, follows a different diplomatic grammar. Yet the Havana meeting and Francis’ overtures to the East pose both an invitation and a challenge. Could there emerge an Orthodox diplomacy of encounter, grounded in synodality, oikonomia, and an ecclesiology of communion, or does the institutional fragmentation of Orthodoxy preclude such a vision? There is much here for Orthodox theologians to consider, particularly whether an “Orthodox soft power” might be imagined, drawing on ascetic witness, diaspora networks, and a eucharistic cosmology. In diplomatic terms, eucharistic cosmology reframes the Church’s presence not as jurisdictional control, but as sacramental offering: a vision of unity-in-diversity where diplomacy extends liturgical communion across ecclesial and geopolitical borders.

The book’s implications for Orthodoxy extend beyond diplomacy. Father Dimitri Tsakas subtly challenges Orthodox churches to develop a global vision, not merely in reaction to papal initiatives, but as a coherent response to a fractured world. What would Orthodox diplomacy look like if shaped by the Trinitarian logic of relationality rather than institutional autocephaly? Could a kenotic, dialogical model emerge from the patristic and hesychastic traditions? These questions are pressing, especially amid geopolitical crises involving Orthodox churches. Between Altars and Alliances calls Orthodox theologians to look beyond jurisdictional rivalries and imagine diplomacy as a liturgical and eschatological presence in the world.

In an age of war, climate collapse, and ideological entrenchment, Francis’ diplomacy, as presented by the author offers a vision not of ecclesiastical dominance but of moral imagination. It is a diplomacy that dares to be uncertain, relational, and open-ended. It prioritises witness over victory, process over posture. And in doing so, it implicitly critiques both secular diplomacy’s obsession with control, and ecclesiastical diplomacy’s tendency toward triumphalism.

Between Altars and Alliances is thus a landmark study that reimagines diplomacy as a theological and spiritual practice, and Francis as a figure who blurs the line between church and world, altar and forum. Father Dimitri Tsakas writes with clarity, erudition, and restraint, offering an analysis that is both grounded and visionary. The book stands out for its interdisciplinarity and accessibility. The author distils complex concepts, such as pluriversality, parrhesia, and ecclesial kenosis, into elegant prose without oversimplification. His treatment of Francis’ meeting with Patriarch Kirill deftly weaves ecclesiological nuance with geopolitical insight, making it engaging for both specialists and general readers. With scholarly precision and lucid style, he opens up ecclesial diplomacy as a vital field of inquiry, charting new directions that link theology, global politics, and moral witness.

In the final analysis, Father Dimitri Tsakas does not ask us to endorse all of Pope Francis’ diplomatic choices. Rather, he urges us to grasp their theological coherence and moral intentionality. In doing so, he establishes a compelling framework for understanding ecclesial diplomacy as a vital mode of ecclesial presence in the modern world. Whether Francis is seen as a bridge-builder or as a disruptor, his reconfiguration of the Church’s global engagement, rooted in encounter, conscience, and pastoral risk, is here rendered with intellectual clarity and spiritual depth. This work stands as a significant contribution to both theological reflection and the study of international relations.

DEAN KALIMNIOU