One Friday night back in the 1940s, Alick Jackomos was travelling on a train heading towards the Victorian city of Shepparton when he met Yorta Yorta / Gunditjmara woman, Merle.

Merle was born in 1929 at the Cummeragunja Mission on the NSW side of the Murray River. She was a key player in the Aboriginal rights movement that had real impact in Australia in the 1950s and ‘60s.

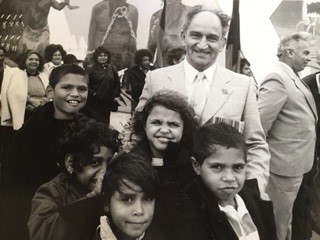

Alick was born in 1924 in Collingwood to Kastellorizian parents. For most of his life, he actively crossed cultural boundaries to associate with and advocate for Aboriginal Victorians. He became known as “the genealogist” of the community, having collected a huge photographic archive of their history.

When these two activists came together that Friday night and later married in 1951, they became a force to be reckoned with as they passionately fought for Aboriginal rights together.

Their three children, Asimina, Andrew and Michael, have also made a significant contribution to the Aboriginal community.

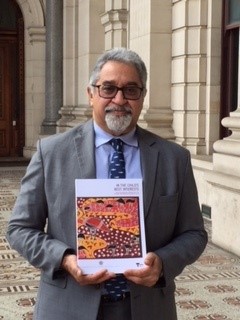

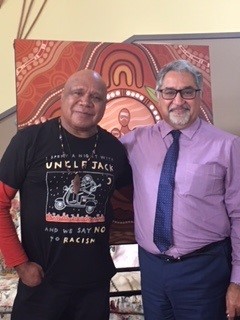

To mark NAIDOC Week, The Greek Herald spoke with Andrew Jackomos PSM to hear all about what it was like growing up with Alick and Merle as parents, and how his work continues to be influenced by them and his Greek Aboriginal heritage.

Different cultures, common traits:

Born in 1952 to Alick and Merle, Andrew is a proud Yorta Yorta / Gunditjmara man.

He tells The Greek Herald how although he primarily grew up in the Aboriginal community because his dad lived and worked in it, he was still ‘encouraged to be proud and knowledgeable’ about his joint heritage.

This involved trying, and subsequently failing, to learn the Greek language.

“At home dad spoke English. Mum couldn’t speak Greek. I attempted many times to go to Greek school on the weekends but I was a complete failure, with football taking precedence,” Andrew says with a laugh.

Despite this, Andrew has travelled to Kastellorizo three times to get a taste of Greek culture and says he has noticed that it shares ‘a lot of similarities’ with the Aboriginal culture.

“We share a joy of family and just the celebration of life, the joy of laughter, the love of good food, the importance of family connections and genealogies, the importance of acknowledging and giving recognition to history,” Andrew explains.

“By living through both cultures, I know democracy and social justice is also critical to both societies and communities. People can come from different backgrounds, different cultures but still find affinity through those basic human traits.”

‘There’s still a long way to go’:

It’s this firm belief in social justice, as well as the example set by his parents, which have since seen Andrew become a highly respected leader in the Victorian Aboriginal community.

Since 2018, he has held the role of Special Adviser for Aboriginal Self-Determination to the Victorian Government. He was also the inaugural Commissioner for Aboriginal Children and Young People in Victoria from 2013 to 2018.

As Commissioner, he was responsible for advocating for and overseeing the provision of state government services to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island children, particularly the most vulnerable in the areas of child protection, youth justice and homelessness.

“The work I’m most proud of is where I undertook an in-depth review of 1,000 Aboriginal children in care to identify how the government system and government-supported community agencies can deliver better outcomes for these children whilst they were in their care,” he says.

During his five-year tenure, Andrew says there were 1,000 Aboriginal children in out-of-home care. Today, there’s roughly 2,500 children.

He concedes ‘there’s still a long way to go’ for Aboriginal rights in Australia.

“I think if you’ve got the skills and the capacity, everybody should be doing their thing to tackle the lack of everybody enjoying the same human rights and access to education and justice,” Andrew says.

For him that means taking on another role promoting Aboriginal participation in the 2026 Commonwealth Games. As part of this role, Andrew hopes to promote ‘a greater recognition of usage of traditional Victorian, traditional Aboriginal cultures in everyday life.’

When we ask why this is so important to him, Andrew says: “Just because you’ve got a certain skin colour, that should not be the pre-determination of why you can’t enjoy the same justice and participation in the economy as other Australians.”

A strong message from a man can’t imagine stopping the fight for Aboriginal rights any time soon.