By Ilias Karagiannis

There are lives that only literature can give the prestige they deserve. History is unable to record them in their entirety. Like that of Katherine Plessou, the first Greek woman to arrive in Australia in 1835. In an era when women were supposed to remain silent, she dared to exist and make breakthroughs alongside the men who wrote history.

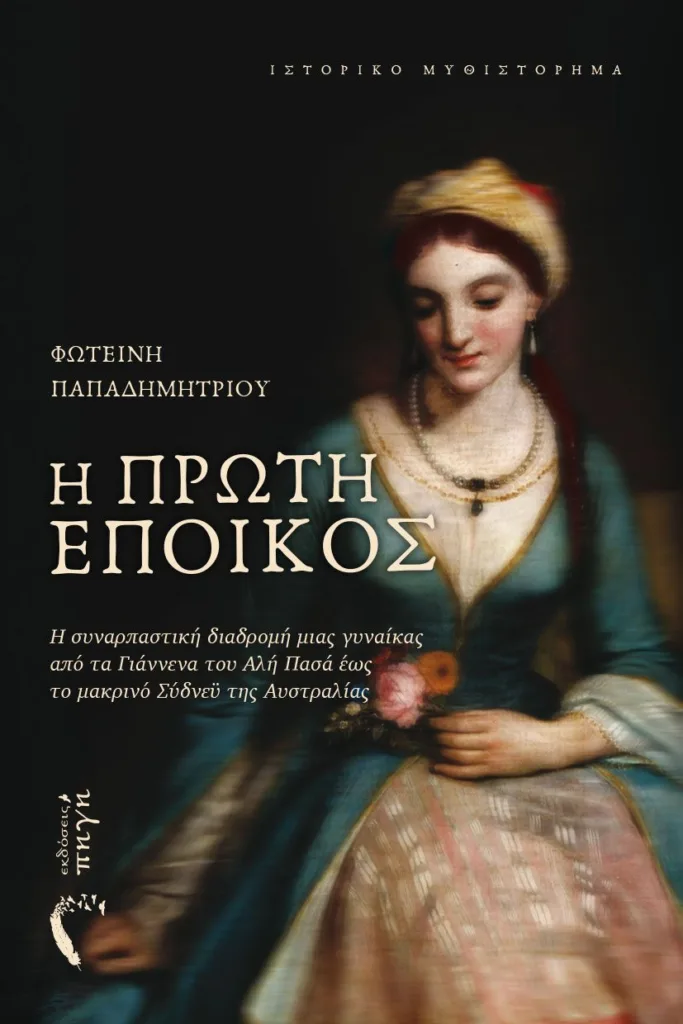

In her new book, The First Settler, paediatrician Fotini Papadimitriou weaves with sensitivity the life of a woman who, from a footnote in history, comes dynamically to the fore decades after her death.

For the Greeks of Australia, Katherine’s journey seems familiar. They too came to the other side of the world, a century later, in search of a better life. Of happiness, a fundamental human right.

Katherine was the first, but she was not alone. The book, in a poetic and tender way, makes us fellow passengers on a journey into the past, into the shared memories that unite the Greek community of Australia like an invisible thread.

Your new book ‘The First Settler’ brings to light the almost unknown story of a larger than life woman, Katherine Plessou. When did you first come into contact with her true story and how did you decide to give her a voice through fiction?

I love history, I love studying it, evaluating it. But true stories, the micro-stories of people that evolve alongside and within historical events, attract me even more. I had just finished my first book, The Despot of the Lake, when Katherine’s story fell into my hands, about four years ago. I read it, I was impressed by her cinematic life, and I said: “this story should be made into a book!”

In the book, we watch Katherine’s life intersect with figures such as Lord Byron, Mavrokordatos, Markos Botsaris. How did you balance fiction with historical accuracy and did you find this delicate balance difficult?

I think this is the bet that the author of a historical novel must win: the functional integration of historical figures, without giving the sense of encyclopedic information. That they participate in the plot, as part of the narrative, as characters in the book, in complete harmony with the fictional heroes, but at the same time that their aura, their displacement, is apparent. And yes, you are right, it is a delicate balance. To achieve this requires both careful study of the sources and imagination. Readers will judge whether, in this case, I have won this bet.

Katherine is recorded as the first Greek woman to land in Australia in 1835. She was, in a way, a precursor to thousands of our readers who made this journey about a century later. What moved you most about her life?

Think of the difficulties she would have faced. The only Greek woman in a new country. There was not even an Orthodox church yet, only the Anglican. But I imagine, as happens in new social systems, there was a lot of help from the British community. Katherine was accompanied by her Irish husband James Crummer, Commander of the 28th Battalion of the British Infantry, and she was certainly accepted as his wife. I tried to “step into her shoes”, to feel her emotions, to read her thoughts.

Katherine arrived in Sydney at the age of 26 with three children, having already lost two. In total, she gave birth to 11 children. In a foreign environment, without help, without her own people. It couldn’t have been easy. But life taught her to endure farewells. For all these reasons, I admire her.

Katherine’s presence in Australia and her settlement in Sydney constitute an almost novelistic finale. Does her migration to the other side of the world symbolise anything?

While Katherine was in Greece, by some dictates of fate, she always walked next to figures who were decisive for the history of our country, such as Ali Pasha, Ioannis Koletis, and Lord Byron. She had a supporting role in historical events, but her story, or even her presence, was never recorded. Historical memory owed her a mention, a role. She had to leave Greece, many miles away, to be given this role. And it happened to be that of the first Greek settler of Australia.

Katherine’s journey resembles a confrontation with fate. From the power of Ali Pasha to love, from the Revolution to emigration, from Greece to Sydney. Do you think that her life is a mirror of the struggle for identity, especially for women of the time, or simply survival in difficult times?

It is both at the same time. Obviously, it is also an adaptation to the dictates of life, which all women of the time accepted fatalistically, an era when the position of women was absolutely secondary. But at the same time, her path was also a process of maturation, a journey of overcoming what was achieved and what was permissible.

Katherine lived a life that even most women of today cannot imagine. She died forgotten. Did you feel, by writing, that you were restoring a historical debt to this woman?

The truth is that in Greece, very few people knew her story. Writing about her, inspired by her, I felt in a way that Katherine had returned to her homeland. The presentation of my book in Ioannina took place in the event hall of the Palace of the Knights, built by Ali Pasha. What a special symbolism!

Your heroine, shortly before the end of her life, takes a journey into memory, into the past. She relives her journey, I imagine as a confrontation with her choices and losses. Why did you choose this form of narration?

I did not choose this specific form, it chose me! I was looking at a photo of her that I found on the internet from Australia and I imagined her very old, reminiscing.

Do you feel that the historical novel has irrevocably won you over? Will you continue on this path?

It has won me over irrevocably and in parallel with my other quality, writing. I will continue on this path, but I will probably detour into other “writing paths”!

You are a doctor and at the same time, a writer. Two seemingly different roles. Do you believe that medicine has offered you a more penetrating way to observe human nature and transfer it to literature?

There are commonalities, I believe, in both Medicine and History, no matter how out of place it may seem at first reading. Commonalities in the search for truth. Medicine has made me seek the truth, the explanation of things. It has given me the tools to search and taught me how my mind should think, in which direction to look. History fascinates me, its study is, among other things, a process of self-knowledge. For this to work, the tools of search are needed. I love both sciences, both “arts” I would say, equally.