For Themistocles Kritikakos, the study of genocide and memory began long before academia – in family stories, silences, and fragments of the past passed down through generations.

Shaped by Asia Minor survivor histories on his mother’s side and wartime trauma on his father’s, Kritikakos grew up acutely aware of how violence and displacement continue to live on within families, even when left unspoken. That lived experience now underpins his scholarly work.

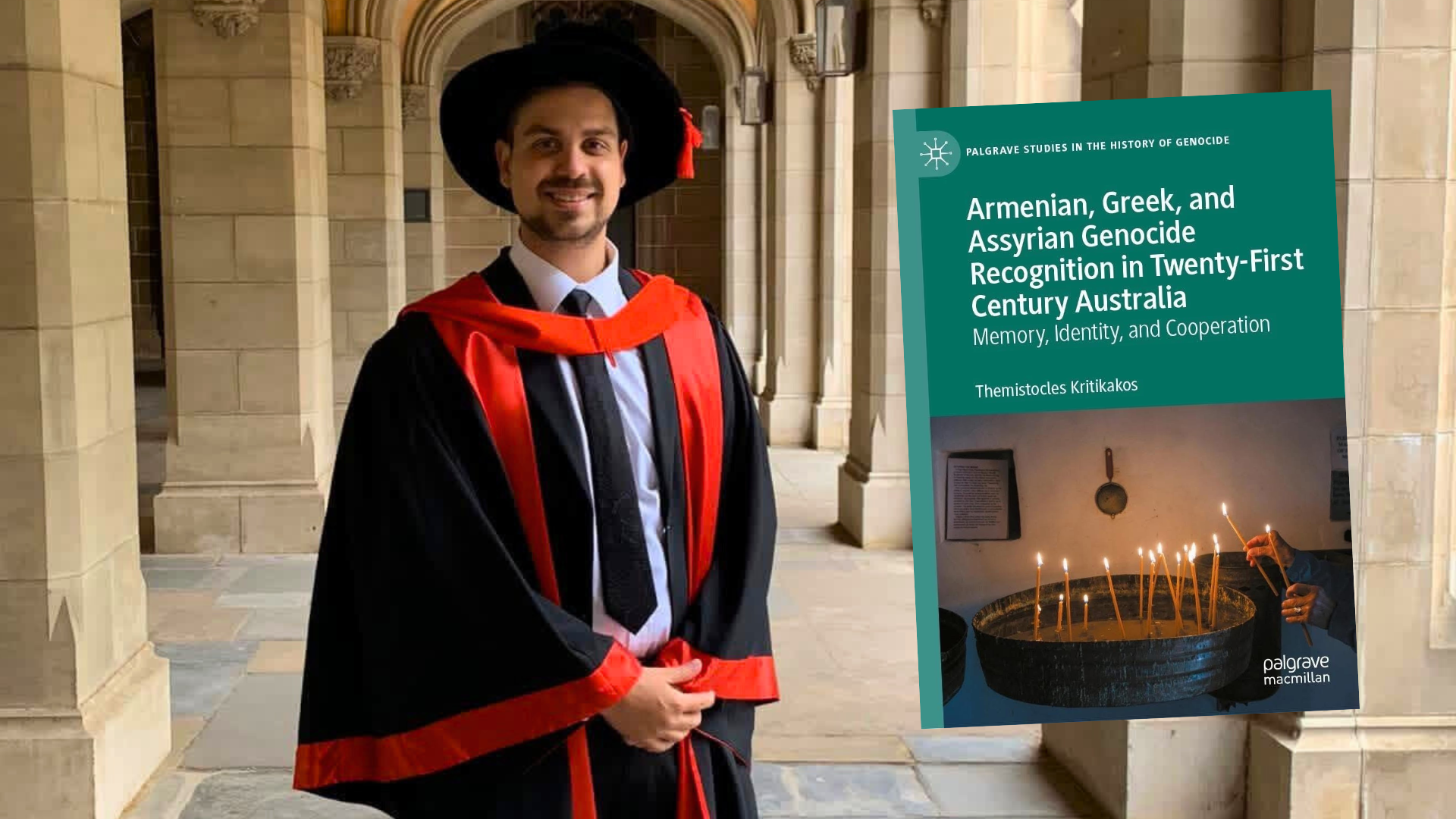

In his new book, Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian Genocide Recognition in Twenty-First Century Australia: Memory, Identity, and Cooperation, Kritikakos examines how Armenian, Greek and Assyrian communities have carried trauma across generations and pursued recognition within the Australian context.

Drawing on oral histories and memory studies, the book explores intergenerational silence, shared remembrance and the complex tension between genocide recognition and Australia’s Gallipoli narrative.

The Greek Herald spoke with Kritikakos about memory, identity and why recognition remains deeply personal more than a century on.

For readers encountering your work for the first time, could you tell us a little about yourself and how you came to focus on genocide and memory studies?

My interest in history began early. Growing up, at family gatherings, in everyday conversations, and even in my father’s barber shop, stories of migration, war, loss, and displacement were part of ordinary life. My mother sparked my interest in this topic and history more broadly by sharing family stories and discussing historical subjects with me, while my father instilled in my siblings and me a deep commitment to education.

Within our family, identity was layered and complex. My mother is from Kastellorizo. To some extent, our Asia Minor heritage was often concealed by a strong and proud Kastellorizian identity within our extended family, yet it continued to surface through fragments of stories, hints, and songs. This reflected a broader pattern within the Greek diaspora, where some histories were emphasised while others were more difficult to articulate.

My maternal grandfather, after whom I was named, was born in 1910 and was a survivor from Kalamaki, today known as Kalkan, in southwest Asia Minor. My maternal grandmother was born in 1919 and was also a survivor, from Livissi, today known as Kayaköy, in southwest Asia Minor. Both lost family members during this period. Like many descendants, it took time to understand and piece together this past.

On my father’s side, there was a different historical experience. My father comes from Elos, a village near Sparta. His family history was shaped by rural life, war, and hardship. There was silence about the past, but also fragmented stories about my grandfather fighting in the Second World War and the brutality he experienced. These different family narratives showed me how memories of traumatic experiences can shape identity in multiple ways.

Learning in our family was a shared experience. We spoke Greek at home and were immersed in the culture daily. My sister helped tutor me in Greek, strengthening my connection to language and culture. My brother, Dr Evangelos Kritikakos, a classicist and philosopher, played an important mentoring role and encouraged my interest in research and academic life.

In high school, with the encouragement of my history teacher, this interest became a genuine passion. I came to see history as something to question, investigate, and understand in depth, and as highly relevant to the present.

At university, I completed an Honours degree in Philosophy before undertaking a PhD in History at the University of Melbourne, specialising in genocide and memory studies. My supervisor, Professor Joy Damousi, had a strong influence on my work.

Alongside this academic path, I grew up learning about the Armenian Genocide and the Holocaust. As I grew older, I became increasingly aware of the long political struggles surrounding Armenian genocide recognition. An Armenian-American band I listened to growing up, System of a Down, and their advocacy around recognition also influenced my interest in the topic at a young age. These factors eventually led me to study the Greek and Assyrian cases as well.

What first drew you to studying the Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian genocides together?

I was drawn to studying these histories together because, while the Armenian Genocide was increasingly recognised and discussed, the Greek and Assyrian experiences remained largely unknown or overlooked. Yet all three communities experienced mass violence during the same period and through similar processes of destruction and displacement. The joint recognition efforts in Australia further prompted me to examine the three groups together.

Examining these histories comparatively allows us to see genocide as a broader process of eradication and homogenisation, rather than as a series of isolated events. These populations were viewed as unassimilable and as internal enemies. A comparative approach helps explain shared experiences of violence, displacement, and loss, while also demonstrating the long-term effects of trauma on the descendants of survivors across time and place.

A holistic approach is therefore necessary—one that draws not only on archives but also on oral histories and memory. These sources help explain why these events continue to matter today and why certain histories have remained overlooked for so long, while also encouraging us to rethink what has been disregarded and how we might approach history differently.

Your book shows that the Greek and Assyrian genocides remain less recognised than the Armenian Genocide. Why is that, particularly in Australia?

In Greece, the legacy of the Greco-Turkish War, internal political divisions, criticisms of the Megali Idea (the vision of a “Great Greece”), and the Asia Minor Catastrophe produced deep feelings of shame and self-blame. These experiences contributed to silence and selective remembering, particularly as Greece later sought reconciliation and diplomatic relations with Turkey. Political engagement with genocide recognition therefore remained limited until Pontian Greeks began pursuing this in the 1980s and 1990s through a revival of culture closely linked to their experience of genocide. This was framed as a Pontian issue and shaped remembrance and advocacy in the diaspora. Later, Asia Minor and Eastern Thrace Greek groups also advocated for recognition.

These efforts were often led by descendants of survivors and refugees, who were sometimes viewed as different within Greek society or treated with hostility. This contributed to fragmentation and to representations of genocide shaped by regional identities rather than by a collective Greek experience.

More broadly, the issue of the Greek Genocide has at times been dismissed politically and academically within Greece for ideological, diplomatic, and geopolitical reasons. Much of the responsibility therefore fell on the diaspora to pursue research and recognition. Over time, this led to a broader understanding of a Greek genocide that encompassed all affected Greek populations. This is why the term Greek genocide is only now used more widely in the diaspora, whereas Pontian genocide was more common previously.

Silence travelled with Greek migrants to countries such as Australia. Memory often remained within families—fragmented and unspoken—rather than publicly articulated. This silence was reinforced by the fact that many migrants to Australia in the 1950s and 1960s had themselves experienced the traumas of the Second World War and the Greek Civil War. By contrast, Greek migration to the United States began earlier and included many direct survivors in the early twentieth century.

For Assyrians, the challenges have been different. Assyrians are a stateless and Indigenous people of Mesopotamia and are internally diverse, shaped by different church affiliations, such as Syriac Orthodox and Chaldean Catholic communities. These differences shaped identities and representation in the diaspora and made unified advocacy more difficult.

Assyrian experiences of persecution, displacement, and genocide also extend beyond the First World War. The Simele massacre of 1933 in Iraq, and more recently ISIS attacks on Assyrian communities in Iraq and Syria between 2014 and 2017, reinforced a sense of ongoing persecution and displacement. Memories of the Assyrian Genocide in the late Ottoman Empire are therefore often understood as part of a longer continuum of survival rather than as a single historical event. Many Assyrians have also arrived in Australia as refugees in recent decades, facing the immediate challenges of settlement alongside memories of contemporary violence.

Armenians, by contrast, have been active in international recognition efforts since the 1960s. They initiated much of the early research and advocacy and paved the way for other communities to better understand and articulate their own experiences, even though the Armenian Genocide was initially the primary focus. The trauma of genocide and pursuit of recognition are a core part of the Armenian identity. Armenian communities in the United States are larger, have a strong lobby, and their diaspora included many direct survivors, given earlier migration patterns, while migration to Australia, as with Greeks and Assyrians, occurred later.

In Australia, these complexities intersected with powerful national narratives shaped by Gallipoli and Australian–Turkish reconciliation. This made coordinated recognition especially challenging, contributed to the marginalisation of these histories within the national story, and required a joint effort from the three communities.

Australia plays a central role in your research, particularly because of Gallipoli. How has this shaped public memory and recognition?

Gallipoli occupies a significant place in Australian national memory as a foundational story of the modern nation. At the same time, through reconciliation with Turkey, it is closely tied to Turkish national narratives, where the campaign is remembered as a moment of triumph associated with Mustafa Kemal Atatürk and the subsequent victory during the Greco-Turkish War of 1919–1922 that led to the creation of the modern Turkish state. These overlapping narratives have made Gallipoli a highly symbolic and sensitive site.

Because the Turkish state does not recognise these events as genocide, recognition carries not only geopolitical implications but also symbolic ones. Gallipoli is linked to access, commemoration, and the protection of Anzac graves, which has encouraged caution in Australian diplomacy and public discourse.

What is often overlooked is that Australians were not distant observers. The Anzac landing coincided directly with the onset of the Armenian Genocide. Greek communities had already been forcibly removed from the Gallipoli Peninsula in the weeks prior. Australian soldiers, prisoners of war, journalists, and humanitarian workers witnessed mass violence and displacement, while Australian relief efforts between 1915 and 1930 supported Armenian, Greek, and Assyrian survivors and refugees.

Far from being peripheral, these events were witnessed, documented, and responded to by Australians in real time. Recognising this history challenges the idea that genocide recognition has little to do with Australia and highlights how deeply these events are connected to Australia’s own wartime experience and international role. These connections have been revisited by researchers and advocates through stories of humanitarianism involving figures such as George Devine Treloar, Sir Stanley Savige, women humanitarians including Joice NanKivell Loch, Jessie Webb, and Edith Glanville, as well as Anglican parishes in Australia, among many others.

What did your interviews reveal about intergenerational trauma and silence?

One of the strongest findings was how trauma persisted even when stories were not openly told. Many descendants inherited fragments rather than full narratives. Silences, emotional reactions, hints, and sudden memories shaped identities in powerful ways and contributed to the transmission of trauma across generations.

There is often a double silence at work: survivors do not speak of the past, and their children do not ask. Many parents sought to shield their children from painful memories, allowing silence to continue. It was often the grandchildren who began asking questions, having enough emotional distance to engage with the past. At the same time, this created a sense of responsibility and a need to come to terms with unresolved trauma. So strong was this influence that many felt these memories as if they were their own. For many people, this process unfolds quietly within families rather than through public activism.

Finally, what do you hope readers take away from the book?

I hope readers understand that genocide does not end when the violence stops. Its consequences continue through silence, denial, and struggles for recognition, shaping individuals, families, and communities long after the events themselves.

People remember and live with trauma in different ways, but it exists regardless of how visible it is. Recognition is therefore not only about justice; it is also about memory, commemoration, and allowing individuals and communities to make sense of their histories and bring them into the public sphere.

I also hope the book encourages reflection on how national narratives are constructed— which stories are included and which are excluded. Through dialogue, negotiation, cooperation, and shared remembrance, communities have shown that recognition does not have to be competitive. Cooperation can create new ways of remembering and strengthen advocacy.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

Genocide remains a pressing issue in the present day. The ethnic cleansing of Armenians from Artsakh demonstrates the persistence of attitudes rooted in 1915, and, alongside genocide against Assyrians in Iraq and Syria between 2014 and 2017, highlights the ongoing need for prevention and acknowledgement.

Moreover, it will be especially interesting to see how future generations, increasingly removed from these histories, come to understand and engage with them within a Greek community that is itself undergoing significant change.

The scholarship on the topic is also growing, particularly in Australia. Important Australian-based research on humanitarianism by scholars such as Joy Damousi, Peter Stanley, Vicken Babkenian, Panayiotis Diamadis, and others has helped place these histories more firmly within Australian history and the public sphere.

As many scholars and advocates have argued, this is also an Australian matter. Recognition therefore matters, as it affirms belonging and acknowledges the experiences of communities within an evolving multicultural Australia. For many descendants, denial and forgetting are seen as completing the very genocidal process itself.