By Mary Sinanidis

A growing number of Greeks around the world are reviving the Ancient Hellenic religion.

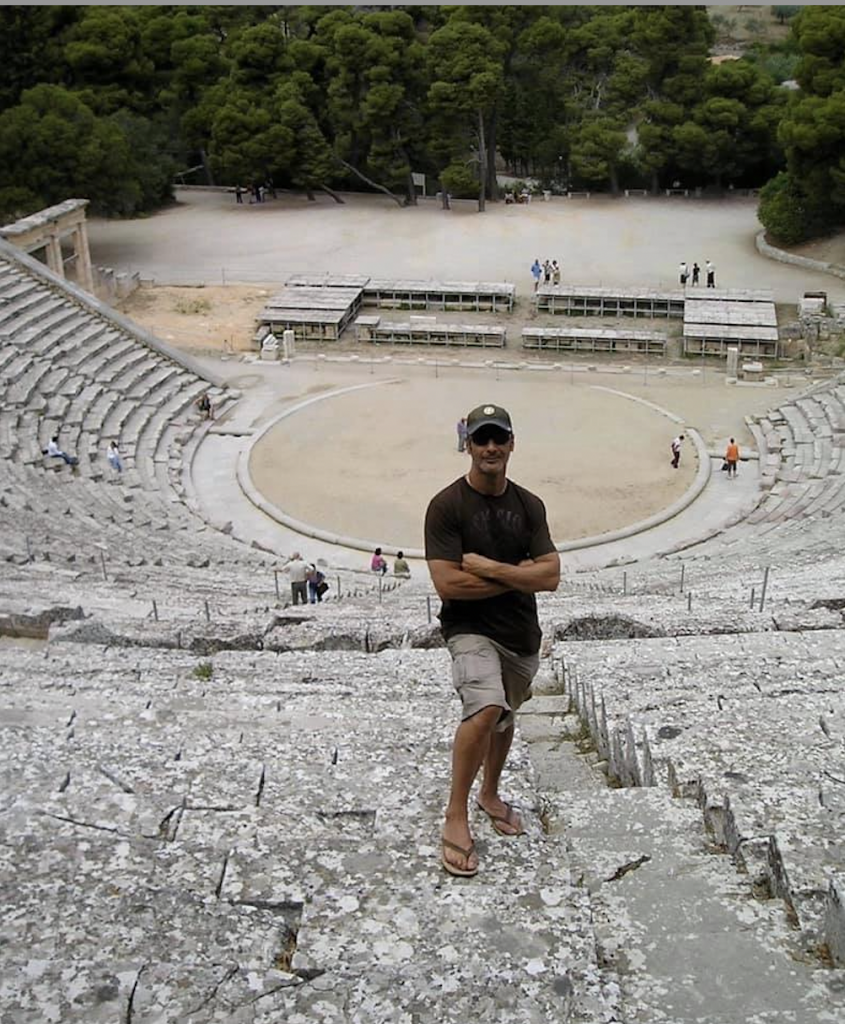

They pray to the Olympian gods and other deities, recite Orphic hymns, seek their faith in philosophy, view the Olympic flame-lighting ceremony as a holy ritual rather than a spectacle, and make pilgrimages to temples of antiquity (where they can pay to visit, but are still forbidden to pray).

They call themselves believers of the original Greek faith, known as the Hellenic Ethnic Religion. They have chapters around the globe, even Australia.

Some call them pagans, idolaters, blasphemists, satanists, and other derogatory terms, but Melburnian blogger/retired businessman Savvas Kallimachos Grigoropoulos, the once right-hand man of a late high-ranking clergyman, rejects these terms.

He states his religion transcends the notion of statues, myths and Dodekatheism.

“We don’t worship statues as idols, but as ideas,” he told The Greek Herald.

“Sure we have statues, but these are to symbolise. Sure we have myths, but these need to be decoded for the hard-core theology to come shining through. Sure there are the 12 gods of Olympus, but there are not just 12 gods, there are thousands of gods, as many as are needed for the functioning of the universe.

“We call them universal divine deities, spiritual forces of power without human forms and bodies but depicted in human forms to simplify and symbolise. They are the law of government controlling the universe, maintaining order and harmony.”

He points to a link between Greek gods and the laws of physics, maths, art, thought and life itself.

“Science went hand in hand with the ancient Greek religion. Theologians also studied science and astronomy, and philosophers were all-rounders. Who does that today?”

Beyond being in awe of ancient Greek contributions to science, maths and the creation of some of the world’s most impressive forms of architecture, “the aim of the Hellenic Ethnic Religion is predominantly to teach us a Hellenic way of life of religious principles and values,” Mr Grigoropoulos said.

He states that while many religions gravitate towards death, his religion is all about how to live.

Praying to the gods

Actor/athlete Harry Pavlidis said he has acquired a heightened awareness as a result of his faith.

He speaks of his “anasa” – breath – as a “miracle”, something simple and complicated at the same time. He wakes up practicing DMT breathing before continuing his laborious morning ritual.

“After my cold shower, I prepare my altar. I have my spondes (libation): wine, water, honey, olive oil, incense, and of course my candle is lit, which is Estia. We offer her first above all, because Estia is my home,” he said.

A great believer in the philosophy of “nous ygieis en somati ygiei” (a healthy mind in a healthy body), Mr Pavlidis treats his body like a temple eating organic food and heading to the Blue Mountains every full moon to collect water from a natural spring, which he has been drinking from for the last 20 years.

“Every month, I bring back 180 litres of nymphs,” he said.

As an actor, he sees himself following the tradition of ancient thespians who used their art as a way to honour the divine rather than focus on fame and fortune, and as a father, he practices his faith with his teenage daughter. He said raising her in the Hellenic Ethnic Religion has helped her shape a unique outlook on life – one not dominated by social media but a life of ethics, morals and critical thinking.

“The ancients didn’t take selfies,” he said, pointing to their efforts to lead virtuous lives.

Reviving ancient beliefs

Members of the Hellenic Ethnic Religion, like Mr Pavlidis and Mr Grigoropoulos, search through ancient texts and cultural relics to reclaim the beliefs of their world-revered ancient forefathers.

Rather than view culture from an objective standpoint, they embrace it.

They meet together for barbecues, hold philosophical discussions, join online groups with members from around the world, visit the Supreme Council of Ethnic Hellenes (YSEE) when they head to Greece where they can take part in outdoor ceremonies with other toga-clad believers.

They take to the countryside for festivities as they are forbidden from praying at ancient Greek temples, which Mr Pavlidis said would make the “ancients turn in their graves”.

Things, however, are looking up for this religion which is gaining membership. It was documented as an actual religion in Greece in February 2017 thanks to work by people such as late activist/author/historiographer Vlassis Rassias, a leading figure in the re-Hellenization movement, hence members can now marry and perform religious rites.

Each year, thousands from around the world head to the Promytheia for their annual bucolic rituals in Litohoroi, a picturesque town at the foot of Mt Olympus.

A number of Greek-Australian believers attend these.

In Australia, the group is still fragmented. Some members even hide their faith from their families, fearing repercussions. Both Mr Pavlidis and Mr Grigoropoulos state that any prejudice they may feel as a result of their religion is nothing compared to what early believers went through when Christianity “was forced upon them” as a “new religion for political purposes”.

“It was a tool to unite the (eastern Roman) empire made up of many different nationalities, to make them loyal,” Mr Grigoropoulos said.

“They didn’t wake up one bright morning, and say ‘oh, we’re giving up our religion’. It was an imposition by the sword. Their temples were destroyed, and on top of these temples were built churches. Their Greek schools were banned, their libraries were banned, their books were burnt, they were forced.”

Mr Pavlidis said 2,000 years “is a long time for people to be conditioned, and it is hard for them to break away from habits and traditions”.

“But just because [these ancient beliefs] have been suppressed for the last 2,000 years doesn’t mean they ceased. Just because mankind said ‘sorry, we’ll move you out of the way and replace you with other faiths” doesn’t mean the gods aren’t present,’ he said. For members of the religion, it’s a connection which can’t be broken.

“I close my eyes, and I do feel their presence inside me,” Mr Pavlidis said.