By Yiannis Paratiritis.

The evening prayers at St Spyridon Greek Orthodox Church in Kingsford include a Prayer of St Ephraim, a 4th century Syrian monk, which is normally recited in Great Lent and which includes the exaltation “Lord and Master of my life, give me not a spirit of idleness, meddling, love of power and idle talk”. [i]

In 2020, Archbishop Makarios, the Primate of the Greek Orthodox Church of Australia, published a book called Love and Master of my life: reflections on spiritual alertness inspired by the prayers of St Ephraim.

Archbishop Makarios adopts the petitions in the prayers and urges the reader to eschew idle talk, the spirit of curiosity (or meddling) and, most importantly, φιλαρχίας (the love of power).

According to Archbishop Makarios, love of power is “self-conceit, pride, the pursuit of leadership, thirst for power, anxiety to rule over others, mania to be the first, lust for authority, ambition in seeking high office and love for every kind of governing position.”

Many would agree with the hierarch of the Greek Orthodox Church in Australia. At another time, but in a similar context, the English Catholic historian and politician, Lord Acton, wrote a letter to the Anglican Archbishop Mandell Creighton in 1887 in which he famously warned of the risks of abuse of ecclesiastical and secular power:

“I cannot accept your canon that we are to judge Pope and King unlike other men, with a favourable presumption that they did no wrong. If there is any presumption it is the other way against holders of power, increasing as the power increases. Historic responsibility has to make up for the want of legal responsibility. Power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely.” [ii]

Dr Kevin Wagner, a lecturer in the School of Philosophy and Theology at the University of Notre Dame in Sydney, wrote a very favourable review of Archbishop Makarios’ Lenten meditations and commented that as readers we need to consider that these words are authored by a man who has been vested with authority and power over two million persons and who is offering a reflection on a spiritual danger he must no doubt be incredibly wary of succumbing to. [iii]

Why is this relevant today?

On 21 November 2022, a majority of parishioners (in person and many more by proxy) of the St Spyridon Parish and Community of South East Sydney voted, on the recommendation of their Parish Council, to change the name to the Greek Orthodox Parish of St Spyridon Sydney and, more significantly, to adopt a new constitution.

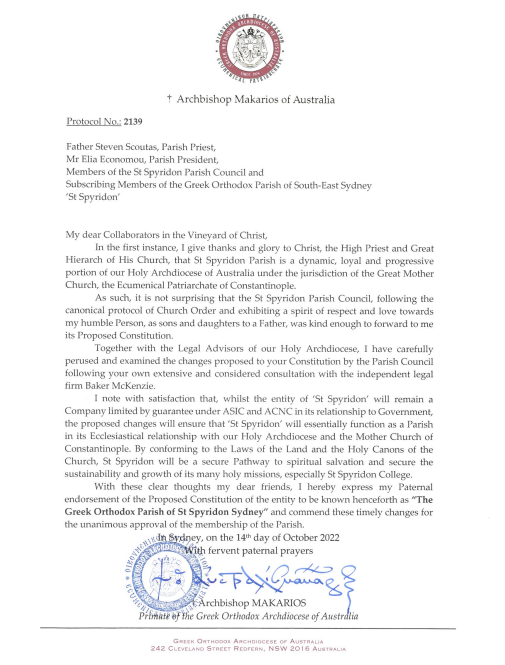

The changes were welcomed by Archbishop Makarios who had urged the members to pursue a “secure Pathway to spiritual salvation” and to adopt a constitution that would conform to the “Laws of the Land and the Holy Canons of the Church.”

The Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew had also supported the changes according to the preamble to the new constitution, wanting the parish and community to transition to a parish in order to “secure its future ecclesiastically.”

And, finally, the Parish Council claimed that the new constitution would “follow the canonical protocol of Church Order” and would align with modern standards of corporate governance for charitable corporations.

However, a close analysis of the new constitution reveals some changes which have started to appear in constitutions being adopted by Greek Orthodox parishes in other parts of the country.

There are a number of provisions that have raised eyebrows within sections of the community and media.

In the just-adopted St Spyridon constitution, a parishioner can now be removed from membership by the Archbishop in his absolute discretion and the Archbishop does not have to provide any reasons for the decision to remove the member. At the same time, any democratically-elected Parish Councillors can also be removed by the Archbishop.

On 25 September 2022, a number of parishes around the country, including the parishes of St Stylianos at Gymea and St Nicholas at Marrickville, the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Parish of Hobart and the parishes of St Raphael East Bentleigh and St Raphael Athelstone, saw new “charters” or constitutions adopted in almost exact terms which have conferred additional wide powers on the Archbishop.

For example, the Archbishop in his absolute discretion may remove a Committee Member from the Parish Administrative Committee, including any Office Bearer, and is not required to give reasons or any cause for that removal.

I am not a theologian or a religious scholar although I am aware that the “Holy Canons” of the church are too numerous to codify. But as a participant in, and observer of, the local Greek community for almost five decades, I am concerned that these recent changes in the (secular) constitutions of parishes such as St Spyridon are not in the true spirit of the Church’s canonical tradition.

The well-regarded historian, Alexander Kitroeff, in his 2020 book The Greek Orthodox Church in America: A Modern History has noted that by the end of the 1930s community secular and religious activities in the US had been subsumed under the parishes which in turn were accountable to the centralised administrative structure of the Archdiocese. Significantly, over the course of the 20th century this hierarchical structure gained such financial strength and influence that Greek Orthodoxy in America increasingly came to be represented by the person of the archbishop.

This development has been mirrored in Australia, first with Archbishop Ezekiel in the 1960s and 1970s who sought to form new community organisations that were always subject to the undisputed authority of the Archbishop, and followed after 1975 by Archbishop Stylianos who was adamant that new parishes be registered in the Archdiocese Property Trust to avoid the disputes and arguments of the past.

Whilst it is understandable that the Greek Orthodox Church in Australia wishes to mould the Greek diasporic identity and at the same time strengthen ties with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, it is important to recall the words of St Ephraim and the warning to guard against seeking power for its own sake.

One of the first books I ever read on the Orthodox Church was by the famous English theologian of the Eastern Orthodox Church, Kallistos (Timothy) Ware. He reminds us that the Orthodox Church is a hierarchical church and although the Hierarch (or archbishop) has a special charisma it is always possible that he may fall into error. According to Bishop Ware, the divine element does not expel the human. The Archbishop remains a man and as such he may make mistakes. The Church is infallible but there is no such thing as personal infallibility.

The vesting of wide discretionary powers in the Greek Orthodox Archbishop of Australia must not be allowed to lead to a potential abuse of ecclesiastical power.

[i] http://www.stspyridon.org.au/ourFaith.php?articleId=96&subMenu=Prayers

[ii] https://oll.libertyfund.org/title/acton-acton-creighton-correspondence

[iii] https://www.catholicweekly.com.au/dr-kevin-wagner-book-review-greek-orthodox-archbishop-makarios/