By Anastasios M. Tamis*

Greece’s victorious participation in the Great War, and the national gains made on its behalf by Eleftherios Venizelos, reinforced political stability and the temporary healing of the intra-communal divisions, which had characterised the political and social relations of the Hellenes since antiquity.

After the end of the Great War (11 November 1918), Greece was one of the countries with the smallest military losses as it entered the war late. Greece mourned the loss and injury of 27,000 men on the battlefields (6,000 dead and missing and 21,000 wounded).

In a territorial sense, it emerged victoriously from the Great War. With the Treaty of Neuilly (November 27, 1919), Western Thrace was ceded to it, while with the Treaty of Sèvres (August 10, 1920), eastern Thrace (up to the edge of Constantinople), the islands of Imbros and Tenedos, as well as the possibility of exercising sovereign rights in the region of Smyrna, were ceded to Hellas. Unfortunately, the Treaty of Sèvres, which Prime Minister Venizelos had solemnly announced in the Greek Parliament, was never ratified, even by the Greek Parliament.

The Greek forces succeeded in liberating, for the second time in a few years, almost all of Eastern Macedonia (Serres, Kavala and Drama). On 17 October 1918, the Sublime Porte had unilaterally signed a Truce Protocol with England in Moudros, without informing the rest of the Western Allies. On 31 October, an allied naval squadron, which included the Greek battle ships of Kilkis and Averof, sailed through the Dardanelles and anchored at the port of Constantinople. At the same time, a detachment of Cretan gendarmes was installed in Phanar, as a garrison of the Patriarchate.[1] It was a symbolic gesture, not of power but of homage.

The Treaty of Sèvres signed by the victorious Allied Powers, the Sultan and Venizelos determined how far the Greek troops could go in the wider area of Izmir. And whilst the Sultan accepted the Treaty, the Young Turks headed by Mustafa Kemal Pasha (1881-1938), revoked it and began to prepare for war, in order to face the Entente and their Greek Allies. This led the Greek government to act, to enforce what had been agreed, with the prospect of gaining additional territory (“Venizelos’ line”). Thus, the Greek troops, ready to fight as they were, organised their landing first and then their establishment in Smyrna; a move that was ratified by the Treaty of Sèvres. They then advanced into the semi-anarchical hinterland of Anatolia, which was plagued by civil strife between the Sultan Mehmed VI Vahideddin, also known as Şahbab (1861-1926), and the Kemalist revolutionaries.

Venizelos rightly believed that the success of his policy in Asia Minor was inextricably intertwined with the economic, political, and military consensus of the British and French Allies. They had, of course, given him their consent and commitment for the Greek landing convoy to accompany the British Navy. In May 1919, by order of Venizelos, the Greek Army campaign for the occupation of the territories of Asia Minor, where the Greek element prevailed and boasted a history of 3000 years of settlement, had begun.[2]

On 10 May, the 8th Cretan Regiment landed in Smyrna and was placed under the command of the1st Division to reinforce its forces. On 16 May 1919, two Companies of the 8th Cretan Regiment landed and occupied the city of Kydonia [Aivali] of Asia Minor and Warrant Officer Kouromichelakis, with the men of the 8th Regiment, undertook military action in this Greek-speaking city and its surrounding territory. The commander of the 8th Cretan Regiment was Colonel Charalambos Loufas (1877-1953;). He was a literati mathematician, who had enlisted in the Greek Army as a conscript in 1895, was promoted to the rank of sergeant in 1896 and participated in the War of 1897. After examinations, he successfully graduated from the School of Non-Commissioned Officers in 1902, and was promoted to Second Lieutenant. He distinguished himself, particularly in the two Balkan Wars; in the Battle of Giannitsa, he captured an entire Turkish company. He did not get involved in the National Schism and in 1919, he was promoted to colonel and Commander of the Cretans.

The scenes of the landing and disembarkation of the 1st Greek Division in Smyrna, ratifying the Treaty of Sèvres, were mixed. “At the behest of the Government, I proceed to the Military Occupation of Smyrna”, wrote the leader of the Division Colonel Nikolaos Zafeiriou (1871-1947) in the proclamation of that day, 2 May 1919. The defeated Turks felt despair and grief. Locked in their homes they lived the terror of the unknown and the imposed occupation. Fear also captivated the leadership of their communal and religious authorities. Colonel N. Zafeiriou convened them in the evening of the same day (2 May 1919), after the first inter-communal incidents, in a gathering, and assured them that there would be an honest and peaceful interracial cohabitation. He guaranteed this to them. However, the Turks trembled at the idea of reprisals on the part of the Greek paramilitary, who would surely seek revenge for the vilification and murder of the Patriarch of the Greeks a hundred years earlier. There was also information that bodies of Turkish irregulars had arrived from the Anatolia and Aidyn to exploit the confusion and chaos that would prevail, following the appearance of the Greek Army.[3]

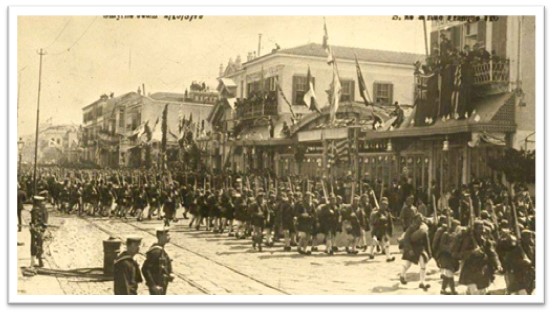

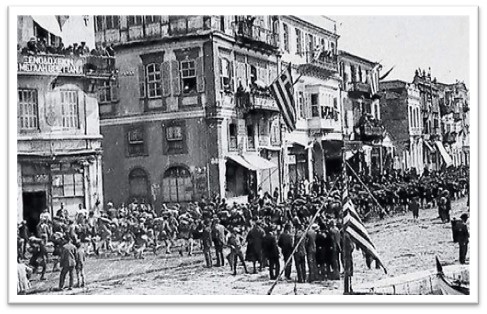

By contrast, the Greeks of Smyrna and surrounding areas gathered in their thousands and flooded the waterfront and the open spaces, delirious with emotion and enthusiasm, and with Greek flags and cries of triumph. In one night, they had ceased to be slaves. They were now Free men, Greek Christians rather than Romioi (ragiades). The first scenes of the disembarkation are depicted in testimonies of the time. [4]

On 5 November, the British ship Minioner 29 was in the port of Smyrna to carry the allied orders. At the end of April 1919, 35 allied warships were anchored in the port, of which six battleships (two British, two French, one Italian and the Greek Averof).

The 1st Greek division landed in Smyrna on 2/15 May 1919. It was transferred there with two ocean liners and twelve passenger ships accompanied by a destroyer and four torpedo boats of the Greek War Fleet. To underline the alliance’s enforcement of the whole project and to prevent any Italian action, the convoy was accompanied by four British destroyers.

From dawn, thousands of Greeks of Smyrna crowded the waterfront to welcome the Greek army. When, at 7:00, the first ocean liner appeared to enter the harbor, thousands of flags unfolded. The disembarkation began at 7:30, while the Smyrnians were on their knees singing the national anthem and the Great Metropolitan Chrysostomos blessed the first soldiers and evzones who stepped on the Ionian land under the instructions of the Division’s leader, Colonel N. Zafeiriou. People and army became one. Emotion was overflowing on both sides. With difficulty, the officers were trying to impose some order. The first phalanx to set off for the interior was that of Colonel K. Tzavelas. The men lined up in fours and moved on, while to the right and left the people were running delirious with emotion and enthusiasm. At one point, as the flag bearer along with the evzone parastatals appeared with the flag, a thunderous noise was heard. The flag bearer and an Evzone were beaten. At the same time, shots began to ring from the windows of hotels and houses. The Greeks had been ambushed by the Turks. They quickly regrouped and began systematic elimination of the armed Turks, while at the same time the commander of the Italian battleship in the port requested permission to land Italian contingents “for the restoration of order”. He was forbidden by the British admiral. Order was restored around 16:00 with many Greeks and Turks dead and wounded. During the unrest, there were also extensive looting and vandalism.

It was suggested that the ambush was set up following an Italian-Turkish understanding. The Italians aimed to blackmail their way into participating in the occupation and administration of Smyrna. They also asked the Turks to convince their own people that the Greeks intended to annihilate them, that they had not come to liberate Smyrna but to conquer Turkey. The Italian goal failed. The Turkish agitation was systematically confronted.

Venizelos himself could not go to Smyrna. But the Deputy President, Emm. Repoulis witnessed the landing. He met the Turkish notables and assured them that the Greek political will was one of peaceful coexistence, as was already the case in Thessalonike since 1912. At the same time, he stated that the Greek state would compensate those who suffered damages. At the same time, the procedure was initiated to identify those who had participated in the looting. Two Evzones were found, as well as other Greeks and Turks. The two Evzones were sentenced to death. The rest received heavy sentences. The execution of the two took place in Smyrna. The Turks there had tangible evidence that they were not in danger.

Ten days later (10 May 1919) the Cretan Regiment, landed in Smyrna, the Giaour Izmir [as Ottomans called it] the little Athens, and served in the 9th Company of the III Battalion, always with the 8th Regiment of the Cretan Division. The landing Greek soldiers felt an overwhelming shiver when their foot left the pier and stepped on the cobbled streets, with his companions. Smyrna reminded him of Thessalonike, not Athens. Twin sisters, one facing the other, one in the East and the other in the West; both in the arms of Archipelagos, the Sea of the Virgin Mary, as the poet says. Both cities with a port and a citadel; both with the same ethnic districts, Muslim, Christian, Jewish and Armenian; both with Frankish neighbourhoods (frangomahalades) with their verhanedes, with their social and economic elite and, both, with their Upper Cities, their Upper Mahalades, where the wealthy and the officials lived, the Turkish and the Greek rulers. Both cities were melding pots of cultures and tribes, the synaxaria of saints and martyrs.

Both cities, despite the pretentiousness of European culture, maintained their neoclassical and eclectic style as well as the Balkan architecture on their homes. The two-storey buildings with their sachnisia, hagiatia and their frourousia dominated the large horizontal avenues of Smyrna. Elsewhere there were various alleys and dense mahalades. Narrow lanes, with low-roof taverns and small shops that sold fried cod with garlic sauce and hapsia, small fish as appetisers. Poorly lit narrow alleys hosting junk and scrap metal shops, blacksmiths, farriers, shacks selling cheap building materials and makeshift foundries and smelters, low night shops where fallen and aged singers sang, outdated courtesans who sold cheap drinks and even cheaper love to sailors, soldiers, bachelors, and deprived spouses. And on the other side, where the three boulevards (boulevardes) began – from the Stock Exchange to the Government House and Tsakmak Bakery and then to the prisons of St. Catherine and St. Demetriou – extended the city which had been modernized by British, French, and Greek engineers and architects. It was the famous engineer, Polycarpos Vitalis, who designed the boulevards as well as the waterfront of Smyrna. He also designed the twenty-kilometre coastal avenue and participated in the construction of the waterfront of Thessalonike in 1870.

During the early nineteenth century, because of the inter-religious conflicts in Crete, thousands of “unhooded” (circumcised) and Islamised Cretans had fled, first to the Dodecanese, and then to the southern part of the city of Smyrna, the old town. In the northern part of Smyrna thousands of merchants from Greece, as well as Europeans and Levantines, British and French, had settled there over the last hundred years and had organised their Orthodox Greek, the considerable Armenian, and Frank neighbourhoods. Smyrna was a strategic port and junction, where all the old trade routes from the East ended. For the Western Europeans, it was a station from where the routes to the Asia Minor hinterland began or ended.

Smyrna had for centuries been a most significant gate for the commercial route that led to the wealth of Anatolia, emerging, mainly from the eighteenth and throughout the nineteenth centuries, as a crossroads where the sea routes of the West ended. The writings of various travellers are replete with references to the special character of the city with its port as its lungs; very vivid images from the life of commerce and the multicultural polychromy of the ethnicities, with the Greek element prevailing in its society.

Greek Army’s daily duty involved patrols in the wider area of Smyrna. During their frequent patrols both in Izmir and on the outskirts, the soldiers were originally living a dream, a world full of love. No matter where they were, the Greeks embraced and kissed them as liberators, offering them sweets, drinks, and flowers. All of them experienced the unbelievable. They saw an enthusiastic Hellenism, and a beautiful city, bigger than Athens, with beautiful buildings, theatres, cinemas, schools, like the Evangelical School, churches, hospitals, institutions, a nice building, the Central Girls’ School, sports clubs such as Panionios, Apollo, Pelops, Greek newspapers, a hippodrome and so much more. However, the situation in Kydonia and Smyrna remained precarious. The Turks “welcomed” the Greek soldiers as conquerors.

The disembarkation of the army caused interracial and interethnic dissension in the big city and fundamentally shook the terms of the cohabitation that prevailed until then, that is for last five hundred years. The Greeks, who had felt enslaved, now felt a dominant community, for the very first time. The Turks felt deprived of the power they had wielded over the Greeks, until then. For most of the Turkish leaders of the city, the absence of a reaction from the Sultan to the occupation of Smyrna by the Greek Army, remained enigmatic and largely strange. The British had already advised the Sublime Porte that the Greeks were in Smyrna with their own consent, and this was because the occupation of Smyrna by the Italians, with whom Turkey had long been at war, was imminent. Families from mixed marriages were also experiencing difficult days. The clashes between the forces supporting the Sultan and those of the Young Turks, as well as the actions of thousands of armed Turkish irregulars, which terrorized the Christian minorities, were fierce and caused upheaval, mainly within the Greek population. The Kemalists first sought put an end to the Ottoman establishment, before turning against the minorities and especially the Greeks, even utilising the armed irregulars, the Tsetes.

The patrols over the next six weeks aimed to bring about a sense of security in the Greek community, as well as a sense of fairness to the Turks. Snipers, uncompromising nationalists, and armed irregular Turks found asylum and protection in the Turkish districts of Smyrna and less in Kydonia. The most intransigent and nationalistic had also taken up arms and often carried out attacks and raids against Christians and Greek soldiers. Colonel Charalambos Loufas’ order was for the men of1st Division to march to the outskirts of Smyrna and arrest or decimate the numerous armed Turkish Tsetes (brigands) whose groups had become the fear and terror of the Christian populations. These mischievous and unscrupulous Turkish militiamen, members of guerrilla groups, and often armed convicted prisoners, constantly harassed the Greek units throughout the border perimeter of the Greek zone…..

The Asia Minor Campaign had begun and flowed victoriously until August 1921. Then a tired Greek Army, decimated by deserters, left-wing internationalists, and Leninists, without allies, away from the supply centers, on the heights of Cale Grotto and in the Salty Desert of Sangarios, and after standing idly by for a whole year, giving the opportunity to Kemal Pasha to be refueled and properly prepared, began their disorderly retreat, leaving behind at the mercy of the Turkish nationalists and militiamen the civilian Greek Christians. The tragedy of Asia Minor Hellenism began in August 1922 and was culminated with the Treaty of Lausanne….

[1] The commanders of many military formations, such as the Frenchman General Anry, the Briton General Millen and Commander-in-Chief d’Espèrey used particularly flattering words when referring to Greece’s contribution to the successful outcome of World War I. The latter, in the Daily Order issued after the Capitulation of Germany, said: “In regards to the Greek Army in particular, I emphasize the zeal, bravery and proverbial momentum that it demonstrated during the glorious role played by it on the banks of Erigos and Axios”.

[2] The number of Greeks living in the territories of Turkey was estimated at 2,400,000, with most of them on the coasts of Asia Minor, Pontus, and Eastern Thrace.

[3] The disembarkation took place in an extremely tense atmosphere and was poorly organised, as the Greek army units did not cut off the escape routes of the Turks who were in the Turkish quarter; a measure that may have discouraged them from resisting. At the time of disembarkation, while the crowds of Greek citizens were welcoming the military departments, Turkish snippers began shooting the Greek soldiers. The Greek forces responded, resulting in the fighting escalating into an all-out battle. The Greeks had 2 dead, 34 soldiers and 9 civilians wounded; the Turks 5 dead, 16 wounded; 47 civilians of various ethnicities were also killed.

[4] See Carolos Brousalis, http://historyreport.gr/index.php/, visit 20.4.2020. Also, Manolis Megalokonomos (1992), “Smyrna – From the archive of a photojournalist”, Hermes Publications, Athens.

*Professor Anastasios M. Tamis taught at Universities in Australia and abroad, was the creator and founding director of the Dardalis Archives of the Hellenic Diaspora and is currently the President of the Australian Institute of Macedonian Studies (AIMS).