When Dr Andrew Holyoake, Postgraduate Research Director at Lincoln University, stumbled upon a box of wartime memorabilia during family history research in 2021, he had no idea it would lead him to a long-forgotten chapter of World War II history.

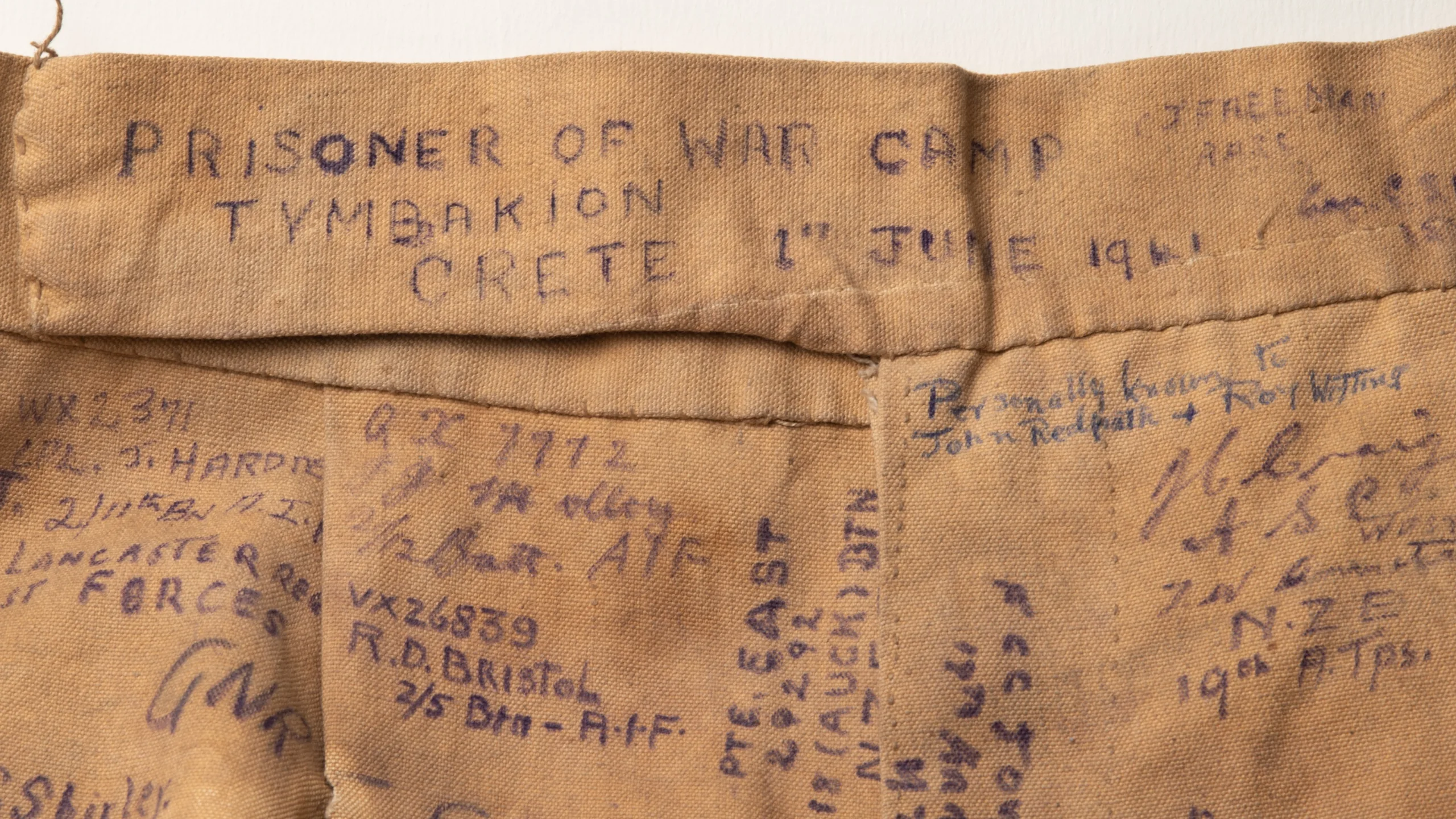

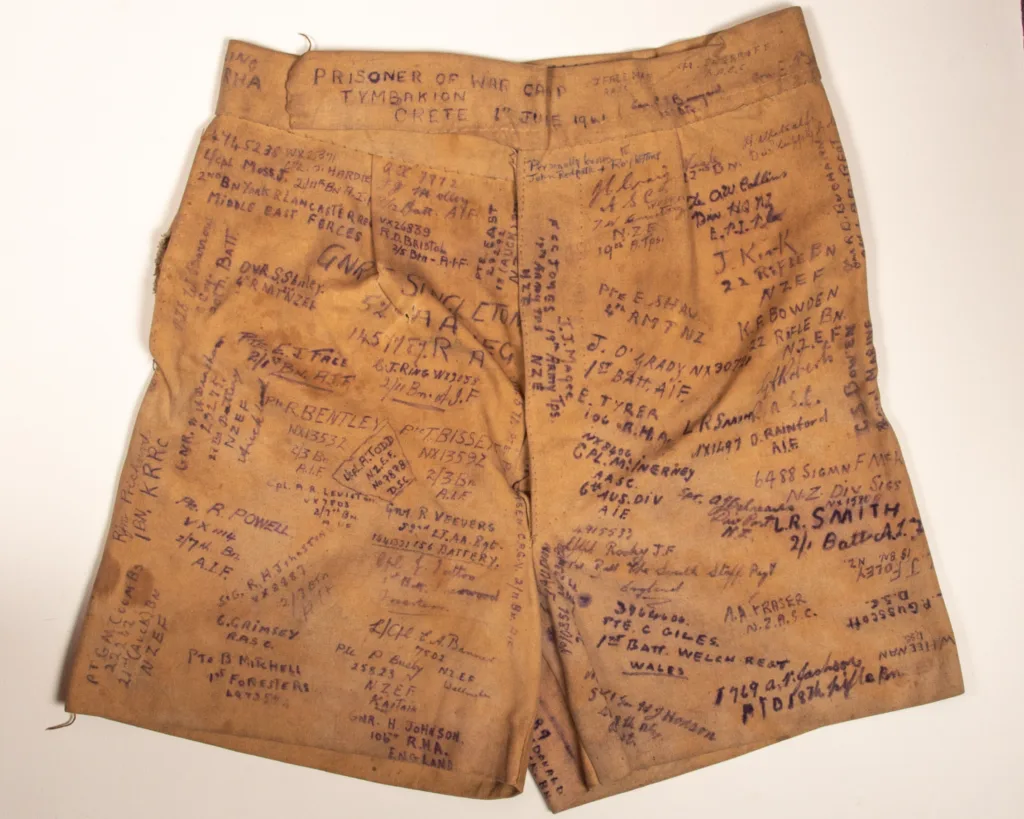

Inside the box was a pair of hand-stitched shorts, covered in signatures and bearing the name “Tymbakion POW camp.” What began as a curious investigation into their authenticity quickly evolved into The Tymbakion Shorts Project — a deep dive into the hidden story of Allied prisoners of war, including many Australians and New Zealanders, who were forced into labour on the island of Crete in late 1941.

In this interview, Dr Holyoake shares how his personal connection through his wife’s grandfather, a POW at Tymbaki, shaped his research; why the September–December 1941 period remains so poorly understood; and how the courage of the Cretan people, who secretly sustained Allied POWs under German occupation, forms the heart of what he describes as a profoundly “ANZAC-Greek story.”

What inspired you to start researching and documenting the story of the Tymbakion Airfield and its connection to Allied POWs and local Cretans?

I was doing family history research in 2021 and my mother-in-law mentioned that she had a chocolate box of war memorabilia from my wife’s grandfather (who died in 1973). Amongst the items in the box was a pair of shorts that were signed by over 120 men and referenced ‘Tymbakion POW camp’. I googled it, and at that stage there were no ‘hits’. I’ve always been a researcher, so thought I’d find out if the shorts were fake, or if there was actually a camp at Tymbakion. I was quite quickly able to link the names of a couple of the people on the shorts with Tymbakion so realised that there was an untold story here. Up until then I knew very little about the Battle of Crete and the POWs.

Your wife’s grandfather was one of the POWs involved in the forced labour at Tymbaki. How has his personal story influenced your work on this project?

Other than the pair of shorts, and a few other things, Bert Chamberlain left no record of his war experiences, but it’s clear that, like many other POWs, he was deeply affected by what he went through. Part of this research is to try to understand Bert’s, and other POW’s, experiences, to help contextualise their lives post war.

The period between September and December 1941 seems pivotal in your research. Why did you choose to focus on this timeframe specifically?

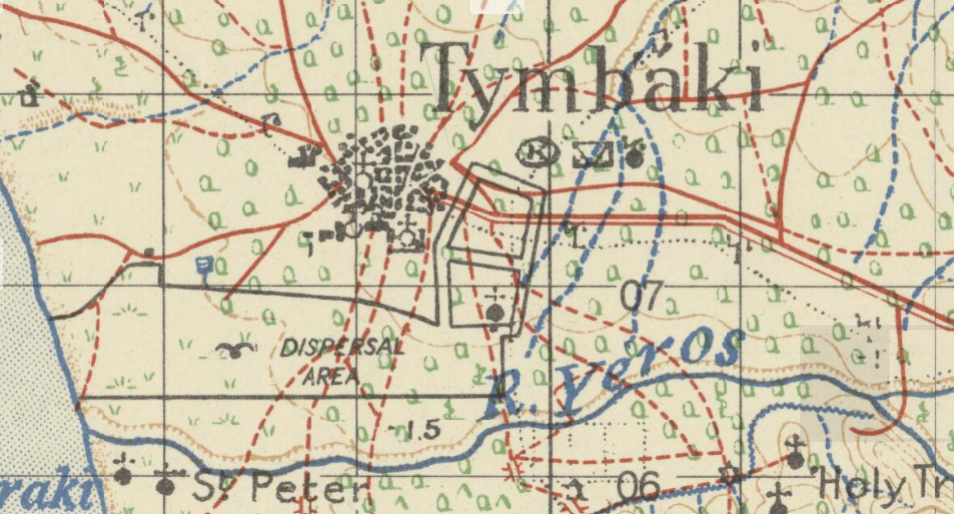

The common narrative is of Allied surrender around 1 June 1941, bringing together POWs to camps on the north coast soon after and then the shipping off of POWs until early September 1941 for processing elsewhere. However, through my research, I’ve discovered there were still around 800 UK and Dominion POWs on Crete at Christmas 1941. These men were processed as POWs on Crete from September 1941, and were in a number of POW camps across Crete, including Tymbakion. They were mostly shipped off in early January 1942. The period from September until December 1941 seems to be little understood, but was actually very active. It seems as though the first group of POWs were shipped/trucked to Tymbakion in mid-September 1941, and did not leave until December 28th 1941.

What has been the most surprising or impactful discovery you’ve made about the interactions between the Allied POWs and the local Cretans?

Quite a lot has been written about the experiences of escapers and evaders on Crete, the support they got from locals, and the frequent, tragic, consequences of this support.

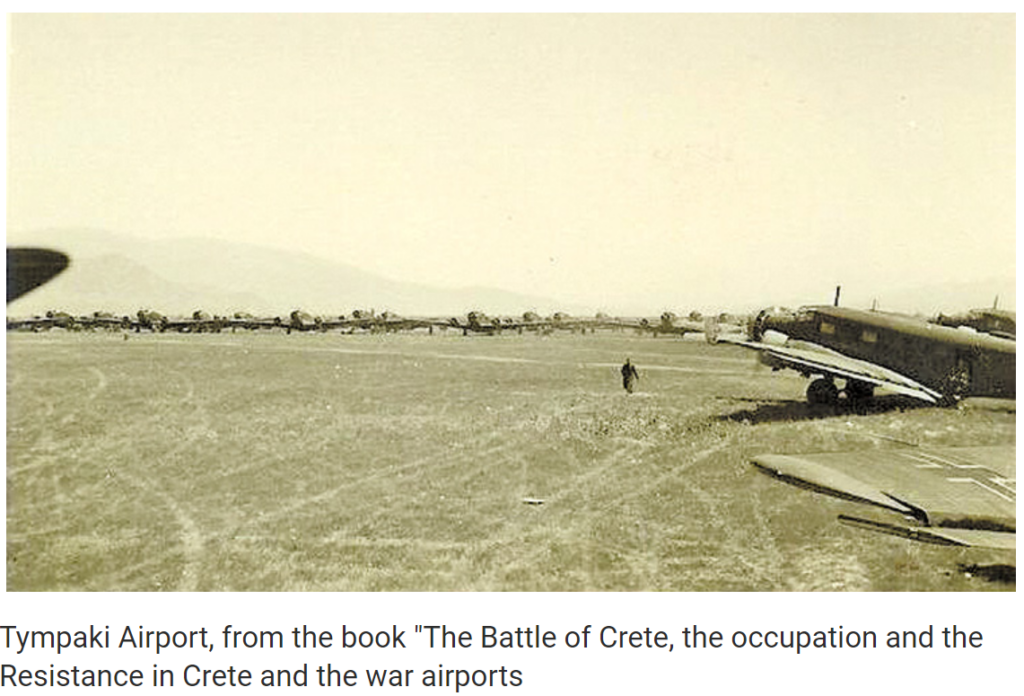

At the Tymbakion camp, the men were doing forced labour, cutting down very old olive trees that were the backbone of the local economy, to prepare land for the airport. When the men came back the next day, they talk of finding food left in the bowls of the trees by the locals. Additionally food was frequently being brought into the camp, essentially sustaining these men, who were on very meagre rations supplied by their German captors. When I talk to Cretans about this, they just shrug their shoulders, seeing it as a long-held tradition of helping others, whereas, from my perspective, they kept these men alive.

Tymbaki holds martyr village status, yet its history remains largely undocumented. Why do you think these stories have remained untold for so long?

After the POWs left in late December 1941, shortly after, the Germans made a decree that locals had to leave the village and that their houses were to be destroyed to provide resources to surface the airfield runways. The locals (and up to as many as 7000 other Cretans from surrounding villages) were then put to forced labour working on the airfield and surrounding fortifications in the early part of 1942. This had a massive impact on Tymbaki that still resonates today. Whilst they rebuilt in the postwar period, a lot of people remained displaced and the POW camp story seems to have been largely forgotten.

You describe the project as an “Aussie-Greek story.” How do you see this narrative resonating with both Australian and Greek communities today?

I think this is an ANZAC-Greek story. Of the close to 800 men who were still in POW camps on Crete at Christmas 1941, about 75% of them were Aussies and Kiwis. It’s clear that they held the Cretans in very high regard, commenting in later diaries about the support they got, and their love for the Cretans. Likewise, I hear that the reception that Aussies and Kiwis get when visiting Crete indicates that the mutual respect is still there today, in later generations.

Many of the POWs forced to work at Tymbaki were Australian, and their experiences intertwine with the sacrifices of the Cretan people. Can you share some anecdotes from that time?

There were Aussie POWs from Queensland, NSW, Victoria, and WA at Tymbakion. In addition to UK and Dominion POWs, there were a number of Greek POWs there as well. Overall, my research has identified about 200 UK and Dominion POWs who were there, making it one of the larger Cretan POW camps in the later part of 1941.

A digger from WA wrote an unpublished diary, detailing his experiences at Tymbakion. In it, he tells of the forced labour they endured, and the harsh conditions that they lived under, but equally he talks about the locals bringing food into camp, especially on religious holidays. The POW camp seems to be organised with an AIF Doctor being the senior officer. The men were told that they were clearing land to make way for a vineyard, but knew all along what was going on, with the first planes landing at the new airfield in mid-October 1941. Others talk of trying to escape and being helped by a family from the village.

The destruction of Tymbaki, including the uprooting of ancient olive trees, must have had a profound impact on local livelihoods. How do you think this legacy is remembered by the current residents?

The impact on Tymbaki, with the forced labour, destruction of the village, post-war maiming by uncleared mines, and the loss of income/heritage, still seems very raw. There is a sense that Tymbaki was set back by decades, and is only now starting to reclaim its identity, and economy. I find it fascinating that the airfield has been in almost continuous use since construction was started by POWs in September 1941, and it is a very dominant part of the Tymbaki townscape; a constant reminder of its past.

What are your long-term goals for the Tymbakion Shorts project? Are you planning a book, documentary, or any other medium to share this important story?

I’m still in the research phase, but think that there is a story here worth telling. I’m working with John Irwin (a Kiwi filmmaker who does a lot on Crete), and will likely try to put together a book. One of the unknowns is exactly where the POW camp was, so a trip to Tymbaki in May 2026 is on the cards, as I’ve never been. Ideally it would be great if Tymbaki was recognised as a significant place in the Battle of Crete/Fortress Crete story, with a connection to a lot of families worldwide.