By Kathy Karageorgiou

As a Greek Australian living in Greece, I like to keep in touch with news, views and events that have to do with Australia. In a recent online search, I was overtaken with excitement at coming across ‘Tarantella’ festivals in Victoria and New South Wales.

My enthusiasm towards Tarantella stems from visiting Naples and Sicily, a few years back. I became fascinated by the culture of Southern Italy, including Magna Graecia – its former Greek colonies since the 8th century BC. There, I was also exposed to a lively dance and its associated music – Tarantella.

Primarily passionate music and dance of abandon and even ecstasy, the Tarantella is believed to have Ancient Greek roots from the Dionysian God of wine and merriment cult, while the Goddess Diana (our ancient Greek Artemis) is also alluded to.

Apparently in Ancient Greece it was only women who attended the Dionysian or Artemis/Diana (goddesses of nature) ceremonies. Centuries later, men joined in on the fun, even incorporating it into warrior rituals until the Romans banned the Tarantella’s predecessor’s celebrations outright in 186 BC.

However, Tarantella dance and its frenetic music could not be thwarted and continued ‘underground’ in Magna Graecia – in areas like Sicily, Naples, Campania, Calabria and Apulia – for centuries. In the Middle Ages, the Church itself was unable to suppress Tarantella’s popularity and incorporated it into Catholicism, even endowing it with a patron saint – St Paul.

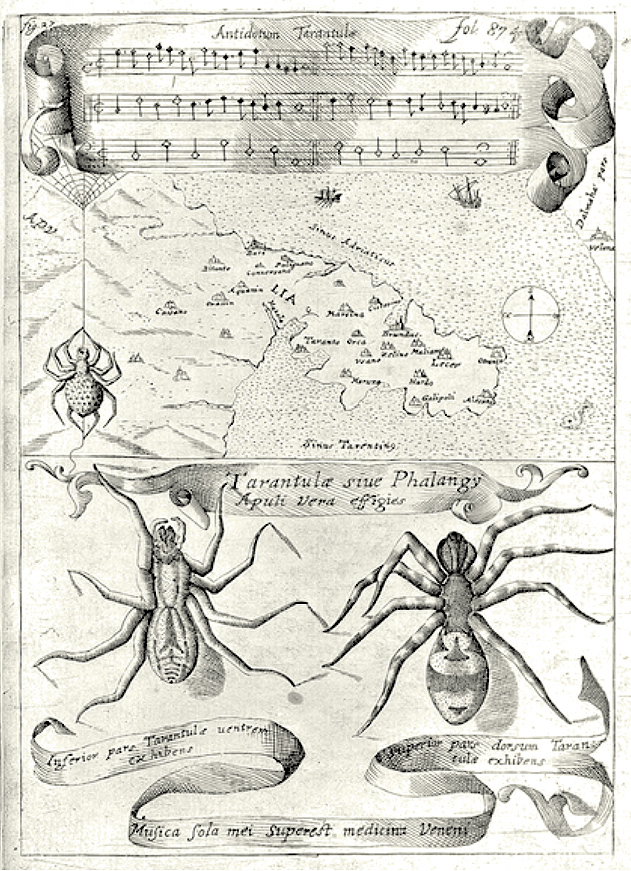

Tarantella’s popularity has certainly not dwindled in modern times either. Salento in Southern Italy’s Apulia region hosts an annual Tarantella festival drawing over 100,000 people. Salento’s city, Taranto (Taras in Ancient Greece or Tarantum in Ancient Roman), is said to be the home of Tarantism, from where the Tarantella got its name.

In Tarantism, the victim is believed to have been bitten by a type of Tarantula spider found in Magna Graecia (some say a black widow spider – linking the ‘female’ to its Ancient Greek mythological origins). The bite causes the person to move or dance spasmodically, encouraged and joined in by concerned family, friends and neighbours so that the spiders poison is expelled from the body. The physical, including acoustic (musical), frenzy lasts for days. Many regard this bite cure (which is also the name of a popular type of Tarentella dance: pizzica – meaning bite), as a metaphor for strong emotional build up, particularly in women, of anger, sadness, depression, and pain in general, whereby the Tarantella served as a catharsis, or even as an exorcism.

When I found out that there was to be a Tarantella concert event here in Patras, Greece as part of a Magna Graecia event and the Carnivale celebrations, nothing could hold me back! The featured musicians included Encardia, as well as others such as the performer who the Melbourne Tarantella Festival’s promotional guide called “The King of Tarantella” himself – Ciccio Nucera.

The evening was fabulous, the music truly powerful and passionate. It was so rousing and moving that it literally moved us onto the dance floor, almost trance like, with first time Tarantella dancing for much of the audience.

So overwhelming an experience was Tarantella that I located the famed “Tarantella King,” musician, singer and dancer Ciccio Nucera – and had a chat with him.

Ciccio pointed out that he is Griko – of Greek background – and speaks the Grecanico language of his grandparents, hailing from the Magna Graecian village Galliciano in Calabria.

“I was born with Tarantella even in my mother’s womb,” he tells me, adding that from the age of two he played the accordianetto (a form of accordion) and the tambourine, explaining that Tarantella involves other instruments – the flute, a form of bagpipes and some guitar too.

“The Greeks influenced Tarantella the most, in its original Grecanico language. There are also traces of Thracian music and dance, like the Zonaradika in Tarantella as well as some Cretan lyra.”

Ciccio refers to Tarantella’s peasant roots, including shepherds with handmade instruments, playing around a fire. The music would prompt the tempo of the Tarantella dance and vice versa, something which I noticed at the Patras concert. Ciccio explains that back then, Tarantella happened spontaneously, but now organisation and effort is needed in the form of festivals and concerts to preserve its tradition.

Asking Ciccio about his time at Melbourne’s Tarantella festival last month, he says that he was enamoured by Australia.

“They keep the traditions alive there, even the 2nd generation of Greeks and Italians do. To Australians the only thing I want to say is that I felt at home there and want to come back. And as for Tarantella – it’s addictive.”

I couldn’t agree more!